In 2007, Oprah Winfrey featured Jenny McCarthy, the former Playboy model turned anti-vaccine activist, on her show to talk about her son Evan’s autism diagnosis. “The University of Google is where I got my degree from,” she said during that appearance. McCarthy would go on to become one of the most visible purveyors of disinformation around vaccines and autism, encouraging countless parents to believe that vaccines give children developmental disabilities.

Before she embarked on this dangerous new path, McCarthy was like other moms — and a majority of caregivers for autistic people are women, particularly moms — trying to figure out how to help their children through the diagnosis. The medical community has a history of marginalizing and discrediting women’s health concerns, and for many years, scientists blamed autism on unloving mothers. So it’s understandable that women like McCarthy went online to try to learn more about the complex, largely misunderstood condition.

McCarthy is an easy target given her large media profile. But throughout the 2000s and through the 2010s, scores of less famous families and solo bloggers spread misinformation through their smaller platforms. These so-called “mommy bloggers” frequently focused on autism and vaccines, even as scientists repeatedly debunked the theory that vaccines played a role in autism. All of this made mainstream media efforts to push back against the lies around vaccines and autism all the more difficult.

Read More

On July 8, something happened to Donald Trump that I’ve not seen happen in the entire decade he has dominated presidential politics. As his base clamored for more disclosures about sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein, his superpower — his ability to grab and redirect attention — briefly failed him. “Are you still talking about Jeffrey Epstein?” he whined when a journalist asked about the Justice Department’s decision to abort any further disclosure of documents related to the case. “This guy’s been talked about for years.”

I’ve spent years tracking Trump’s favorite attention-management tactics, including in a 14-part podcast. And for several weeks in July, he cycled through all of them, attempting to focus attention somewhere other than Epstein. He tried polarization, claiming that the Epstein scandal, which his own aides and oldest son had stoked just months earlier, was instead just a Democratic hoax. He tried threats, attacking those who clamored for more. “I’ve lost a lot of faith in certain people,” he complained, “Some stupid Republicans and foolish Republicans fall into the net, and so they try and do the Democrats’ work.” Even after Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche met with Epstein’s associate, the convicted sex trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell, conducting a scripted proffer designed to minimize her crimes, Trump was left offering up a list of things he wanted people to cover instead of his own ties to Epstein. The most successful ploy was the same one he has used since 2018, chanting Russia Russia Russia. On July 18, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard renewed old complaints about the Russia investigation, screaming treason and blaming Barack Obama.

It took 10 days, threats against right-wing influencers still focused on Epstein, and Gabbard’s conspiracy theory before Trump started to reclaim his ability to redirect the media’s attention.

Read More

There’s a cabinet in my apartment that tells the story of how journalism broke during the pandemic. Vitamins, supplements, mushroom coffee from the Midwest, superfood powders from the Amazon, prebiotic syrup from Japan, bone marrow protein from England, liver detox from a lab — each bottle represents a different “expert” I encountered online, a fragment of information that promised to reveal what mainstream media wouldn’t tell me. About 90% of these purchases were triggered by social media ads that positioned themselves as news sources, alternative journalism, citizen reporting.

This cabinet is a physical manifestation of the COVID-19 infodemic — the first time in human history that a global crisis unfolded entirely within social media platforms, where the line between news, advertising, and conspiracy theory dissolved completely. Traditional journalism competed directly with wellness influencers, political provocateurs, and foreign disinformation campaigns. The World Health Organization adopted the term, warning that we were fighting not just a pandemic, but an “infodemic” — a parallel epidemic of misinformation that spread faster than the virus itself.

I had become both victim to and perpetrator of this information chaos, an unlicensed curator of alternative facts, dispensing health advice to friends based on Instagram stories and Facebook ads that masqueraded as investigative journalism.

Read More

I first realized the extent of the internet’s takeover of U.S. politics while standing in the lobby of a drab hotel convention center, listening to an elderly gentleman rattle off a list of fringe conspiracy forums he frequented.

Read More

At the very start of the second Trump administration when multiple explosive news stories were breaking every day, I got a scoop that changed the course of my career. When I received the tip, there was no editor to run it by; no legal team to consult. I had to decide in a moment of sheer terror and exhilaration what my next move should be. Then I hit publish — and scooped all of the country’s biggest news outlets by reporting that the federal government planned on freezing all funding for grants and loans. The move caused such an uproar that the federal government walked it back, and my work as an independent journalist saw unprecedented attention.

One of the most drastic changes in journalism of the last 25 years is accountability to readers. In the era before digital media really took off, journalists would write and publish stories and maybe receive an occasional letter or email in response to their work. Now there is an invisible umbilical cord between writers and readers. When I broke the federal grant story, I did so on Bluesky, and hundreds of people immediately responded, expressing outrage and disbelief that the administration was exerting such a heavy hand so soon into its tenure.

This inextricable connection is no coincidence: With the rise of social platforms like YouTube and Instagram that highlighted individual creators, the need to sell one’s self along with one’s work became essential. Just before graduating journalism school in 2009, my senior seminar professor had us all sign up for Twitter accounts; while that arguably set me up for the circuitous path to where I am now, it also encouraged me to emphasize not just the political but the personal. My thoughts on The Bachelor were stacked on top of reporting about the Affordable Care Act — and people could read and react to every single one.

Read More

Writing about the failure of patron-supported journalism is itself a kind of confession. It hasn’t worked for me, and I struggle to weigh my guilt around that (should have worked harder!) against what I know is a structural problem. Patron-supported journalism (including newsletters) is both a throwback to the earliest mode of media production and, as it exists today, the newest way for capitalism to suffocate dissent.

Read More

My favorite political blog post of all time was published by Jim Newell on the manic site Wonkette.com on September 12, 2008, at the height of the hope-and-change era preceding Obama’s first election. Its headline is, “Typical Florida Person Creates Year’s Best Campaign Sign.” The entire body of the post, cribbed from a long-disappeared local news story, consists of a closeup photo of a handmade plywood yard sign that reads “OBAMA HALF-BREED MUSLIN,” accompanied by two sentences of the news story: “Lacasse put the sign in his front yard four days ago. ‘If I see anybody touching that sign, I got a club sitting right over there,’ Lacasse said.”

The original story, to be sure, had the name and age of the man and relevant background facts and context. But the blog post had everything you really needed to know. He got a club sitting right over there.

When the blog era really got rolling in the late aughts, much of the traditional media dismissed bloggers as amateurish and borderline unethical pretenders to the title of “journalists.” Bloggers, the traditional wisdom went, were young, snide purveyors of dashed-off riffs on the weightier work of Real Reporters, a band of irresponsible little shits making fun of writers whose prestige they would never match.

Well. Not all of us were so young. The rest of the criticism was kind of true. Still, as the golden age of blogs recedes in the rearview mirror, one point about the editorial legacy of bloggers demands to be made. For all of the derision that traditional journalism heaped upon them, I’d argue that good bloggers have better editorial judgment than any other type of writer.

Read More

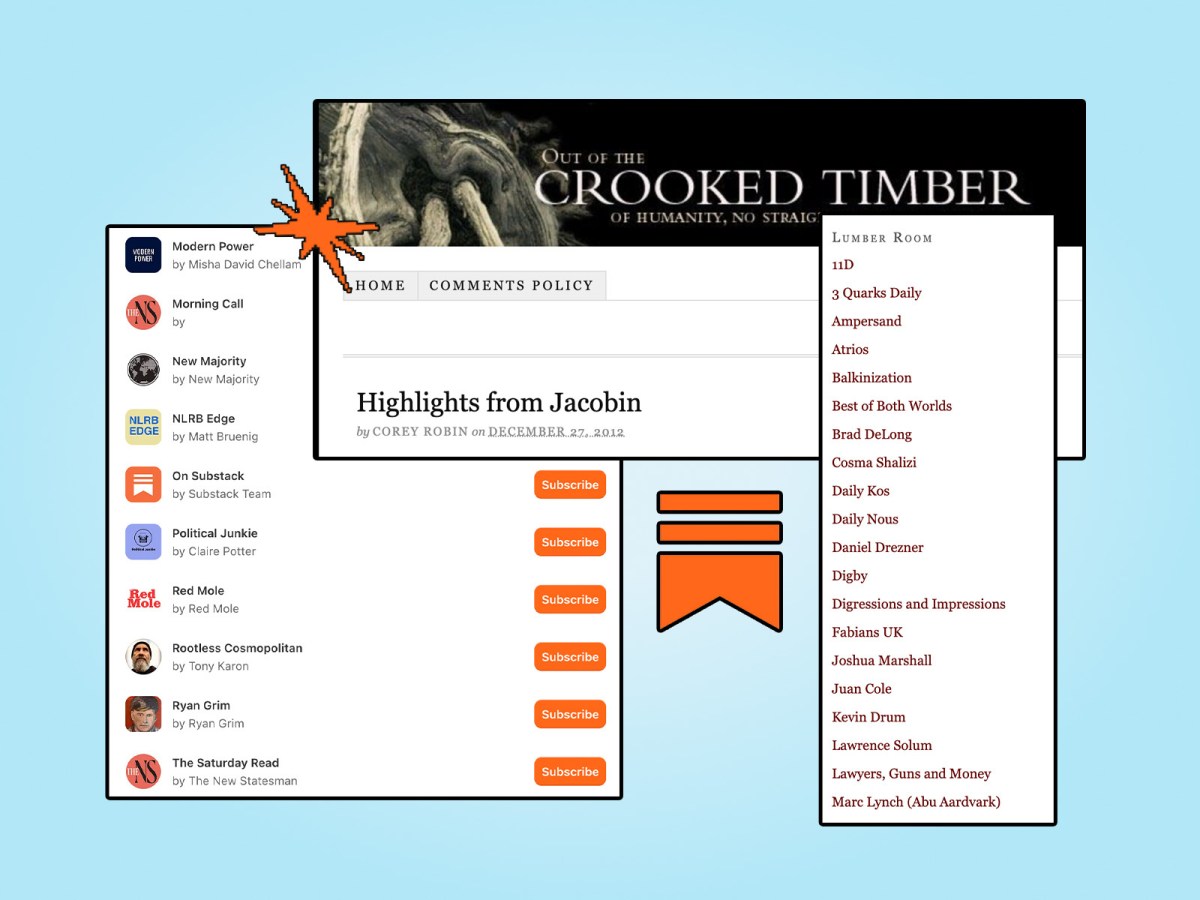

When I started Jacobin in 2010, my first milestone of the magazine “making it” wasn’t a glossy cover or a TV hit. It was landing on a Crooked Timber sidebar.

Read More

You can leave journalism altogether or you can take the longest way around the barn possible to try and keep doing it (and maybe, in the process, save local journalism).

That was the choice that I and four other journalists were facing in fall 2021, after witnessing countless talented colleagues get fired, pushed out, or just endure being grievously underpaid until they said fuck it and quit, that they’d had it with an industry marred by catastrophically inept management decisions. Staring down the middle parts of our careers, the landscape where we had begun our time in journalism was completely cratered out — the once voluminous flow of investment into digital media had dried up, while the local news outlets where we cut our teeth were blinking out, little fires smothered by hedge fund buyouts and consolidation. Everything was getting balkanized, with popular writers from the internet launching their own Substacks after their publications died. The funders for non-profit journalism were, as ever, wildly up their own asses and couldn’t figure out how to sustainably fund or scale a newsroom. Google and Facebook had devoured whatever was once financially enticing about publishing on the internet, with their wild overpromise of ad revenue from clicks.

Read More

Here in New Orleans, if you want to go out and buy a print magazine, good luck. Newsstands are essentially a thing of the past, and few bookstores still stock periodicals. The situation is the same across the country. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, for instance, the beloved newsstand that anchored Harvard Square for decades closed in 2019. The nearby Harvard Coop bookstore also got rid of its magazine section to make room for more university-branded sweatshirts and other souvenirs.

The less I see of newsstands, the more I worry for the country, because magazines are vital for the health of democracy.

Read More

- Sarah Jaffe

- Matt Pearce

- Brian Beutler

- Kylie Cheung

- Megan Greenwell

- David Weigel

- Jon Allsop

- Adam Mahoney

- Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

- Sarah Posner

- Jeet Heer

- Andrew Parsons

- Eric Garcia

- Marcy Wheeler

- Aurin Squire

- Kelly Weill

- Marisa Kabas

- Ana Marie Cox

- Hamilton Nolan

- Bhaskar Sunkara

- Nathan J. Robinson

- Max Rivlin-Nadler

- David Dayen

- Elizabeth Spiers

- Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

- Max Rivlin-Nadler

- Bhaskar Sunkara

- Hamilton Nolan

- Ana Marie Cox

- Marisa Kabas

- Kelly Weill

- Aurin Squire

- Marcy Wheeler

- Andrew Parsons

- Jeet Heer

- Sarah Posner

- Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

- Jon Allsop

- Adam Mahoney

- David Weigel

- Kylie Cheung

- Brian Beutler

- Megan Greenwell

- Matt Pearce

- Sarah Jaffe