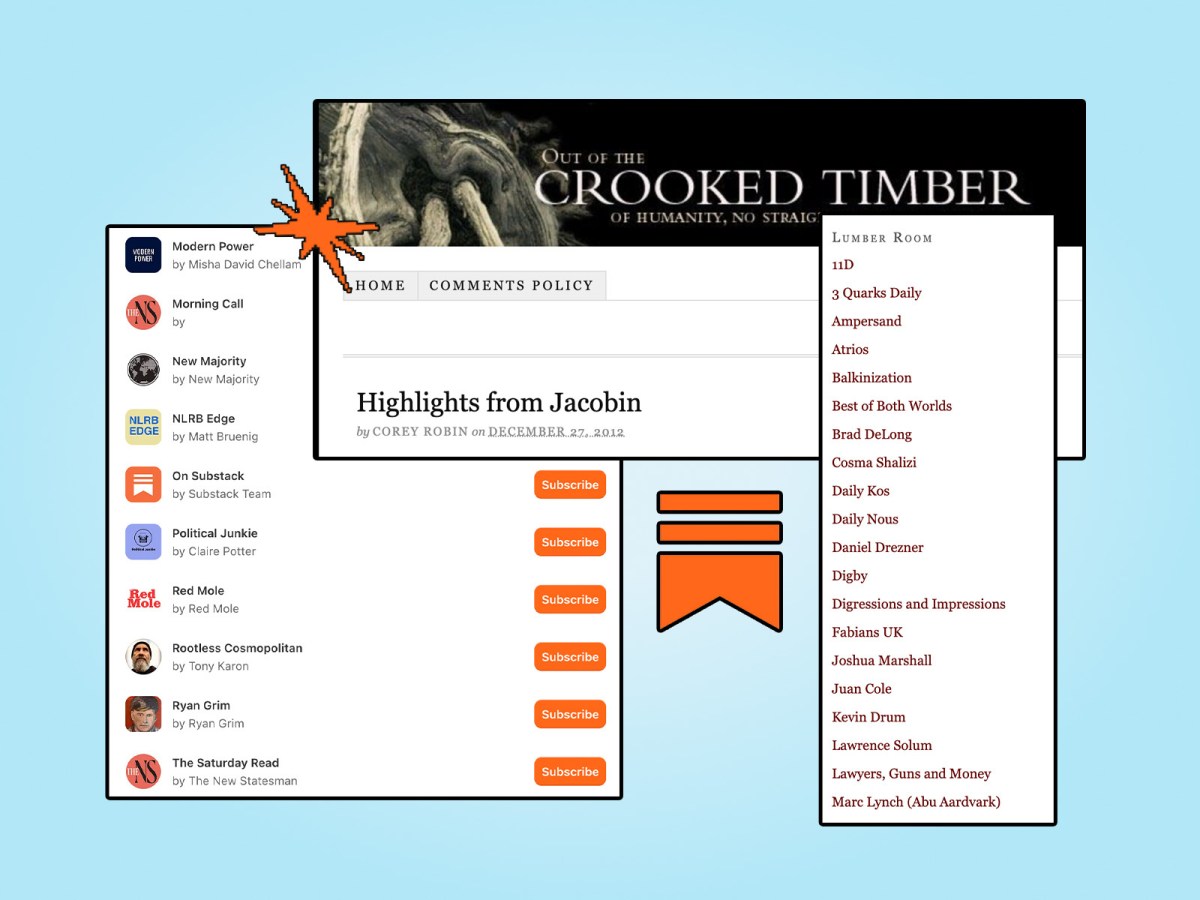

When I started Jacobin in 2010, my first milestone of the magazine “making it” wasn’t a glossy cover or a TV hit. It was landing on a Crooked Timber sidebar.

If you came of age in the mid-to-late 2000s, you know the sidebar I mean: that “blogroll” column of outbound links on sites like Crooked Timber, Marginal Revolution, Brad DeLong’s Grasping Reality, Arts & Letters Daily, and a hundred smaller publications run by academics, policy wonks, and obsessives who wrote far more than their jobs required. A link there wasn’t an algorithmic lottery ticket, it was a handshake.

For a tiny socialist magazine published out of an undergraduate’s dorm room, those handshakes mattered. Jacobin’s early writers and editors were not products of a newsroom or think tank, we were strangers from listservs — specifically LBO-Talk, the scrappy community that cohered around Doug Henwood’s Left Business Observer. LBO-Talk taught many of us how to argue with numbers and footnotes without losing sight of class. It was rowdy but bounded, a space where reputations accrued and were put at risk, moderated by norms and by the threat of being kicked off a list you actually cared to be on.

That was the secret sauce of the political blogosphere at its peak: it felt simultaneously democratic and curated. You read people who took time to understand a subject, and then, in their comment sections or on your own blog, you argued back. “Trackback pings” stitched these conversations together. RSS readers made sure you didn’t miss the next round. The result wasn’t a canon, but a shared public square with porous borders.

For Jacobin, being pulled into that conversational mesh was a shortcut to legitimacy. The blog world rewarded the two things a small magazine could actually control: argument and persistence. If you were right early and often, the links came. If you were wrong but in an interesting enough way, the links sometimes came anyway. That environment helped a fringe socialist project reach beyond the hard-left ecosystem and engage liberals, social democrats, even a few libertarians who wandered by to spar. In parallel, we consolidated writers and editors from listservs, scattered socialist organizations, and small journals into something like a political center with editorial processes and deadlines. The online conversation gave us oxygen, but building a real magazine gave us lungs.

What killed the older blog world many of us are nostalgic for today? On the Anglophone socialist left, one bittersweet answer might be the rise of Jacobin as an institution. But for the infinitely larger sphere of non-socialist political publishing, we should look to Silicon Valley. Facebook’s evolution dismantled the link economy and replaced it with the feed. Twitter’s growth mimicked a comment section or listserv but, without a fixed community, bred more viciousness and less grace. Then the ride got rough: the “pivot to video” and publishers chasing algorithm changes instead of building and owning their audiences and data. Each turn discouraged the slow, threaded debates blogs excelled at and rewarded short-form performances tuned to platform whims. Conversation migrated, but it also thinned out.

The messy civic squares of comment sections either withered or were shut down by publishers who rightly feared libel, abuse, and bot swarms. One of the first things I did when I joined The Nation in 2022 was disable Disqus, our comment system. But these types of discussions didn’t vanish; they fragmented. Some moved to private Slacks or Discords where the incentives skewed toward cohesion, while some metastasized into quote-tweet pile-ons, where the incentive is attention through denunciation. What we lost wasn’t only a set of sites, it was a structure of attention that turned heterogeneous audiences into overlapping publics.

The current newsletter boom at which Substack is at the center looks, at first glance, like a restoration. The direct relationship with readers resembles RSS in spirit; writers own their mailing list; comments exist again; the pressure to feed an algorithm exists but is tempered. In an alternative timeline, a 21-year-old me might have skipped the headaches of payrolls and print runs and simply built a sustainable socialist newsletter with a few dozen contributors and a few hundred paying supporters. A few well-timed pieces in mainstream outlets, some podcast appearances, and you could occasionally move a debate.

I won’t pretend that’s a bad option. The democratization of tools and the normalization of reader revenue have made it possible for dissident writers — left and right alike — to speak directly to audiences and bypass the groupthink of the professional editor caste. It has also made possible what the blogosphere never quite achieved: a path to economic viability for small-scale political media without advertising, foundation money, or book advances. That’s a welcome step forward.

And Substack has another feature that reminds me of the blogosphere. The older blog world was fundamentally interdependent. Its culture was outward-facing: link to argue, link to endorse, link to say, “if you’re reading me, you should read them.” Newsletters are, by default, inward-facing. Their unit of distribution is the inbox, not the open web. The Substack recommendation engine replicates the earlier model to some degree, however. When setting up their publication, authors can select other newsletters they admire and promote them. New readers see these recommendations during the signup flow, creating the appearance of a positive-sum relationship between competition newsletters and the sense of a shared community. It’s not algorithmic — everything is chosen and curated by the writers themselves.

Still, despite this feature, and though crossposting and linking persist on the platform, it rarely produces a sprawling, multi-site conversation that a curious bystander can read in one sitting. We seem to be building fewer lasting collective institutions and more ephemeral vehicles for individual advancement. Plus, paywalls, necessary as they are to sustain writers, turn arguments into gated micro-publics.

While some aspects of Substack may harken back to an older form of political publishing, it doesn’t seem to be reviving the sturdy communities that made the best political blogs feel special. If Crooked Timber today is a living remnant of that order, it looks like Byzantium in its last century: storied and cultured, but a city-state that was once an empire.

I appreciate the insight of how things started, where they were, how they’ve changed and what’s happening now.

One of the problems is that each of these sites requires payment and for most of us, that means that we have to be careful about how many we sign up for.

That’s true of many sites but I’m not sure you could even say “most” of them work that way—many sites have a paywall for some but not all of their posts, and even the Bulwark (at a hefty $100 per year) has a ton of free content.

You’re right that the paid subscription is a difference from the blogosphere of old, but I didn’t want people not to investigate the good content that’s out there because of perceptions that it’s all behind a paywall.

I’m sad to see Substack linked here given their overt support of Nazis.

There are plenty of platforms. Please don’t patronize Substack.

Two problems I have with substack: the payment scheme for individual writers (unlike TPM, which is a news organ all on its own) basically is pushing out the non-wealthy. I’m on a fixed income now, and have to pick careful where I spend my media budget.

The other, of course, is the Nazi issue. For example: Substack promotes a Nazi

I won’t give my dollars to a platform that has that. Period.