NEW YORK — Opening statements in the first-ever criminal trial of a former President kicked off Monday morning with prosecutors accusing Trump of “election fraud” as the defense asked jurors to take a jaundiced view of the case.

Continue reading “Trump Opening Statements: ‘Election Fraud,’ Fake News, And An Appeal To Exhaustion”Liberal Justices Come Out Swinging In Uphill Battle Over Criminalizing Homelessness

The liberal justices pounced aggressively in oral arguments Monday over a city ban on sleeping outside with a blanket, less indicative of a full-court press to sway their right-wing colleagues to their side and more an attempt to put their stamp on a case they know cannot be won.

Continue reading “Liberal Justices Come Out Swinging In Uphill Battle Over Criminalizing Homelessness”All Talk Marge

Like David, I’m still not clear that we have a satisfying explanation of just why the last week on Capitol Hill happened. For the moment I’m just glad it happened. Ukraine will now get a major infusion of military aid which should at least stabilize the Ukrainian war effort. But even if we don’t really know why Mike Johnson did what he did, there are some other takeaways worth noting.

Continue reading “All Talk Marge”Prosecutors, Defense Make Their Opening Arguments In Trump’s First Criminal Trial

Follow along with us below as we cover the first criminal trial of a former U.S. President.

That’s A Wrap

Opening statements are complete in the Trump trial, and our Josh Kovensky has done a tremendous job covering it in real time.

If you’re going to use your lunch break to catch up on what you missed, start here.

Awww, House Mows Over MTG On Way To Passing Ukraine Aid

A lot of things happened. Here are some of the things. This is TPM’s Morning Memo. Sign up for the email version.

Not A Good Weekend For MTG

The compromised-by-Russian-propaganda House GOP was not enough to stop House Democrats and less-crazy Republicans from helping Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) finally pass Ukraine aid over the weekend – leaving Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and her motion to oust Johnson twisting in the wind.

The Republican-on-Republican infighting was something to behold:

Let’s be real clear though: A majority of the House GOP conference still voted against the Ukraine aid, so there hasn’t been some seismic shift on the Republican side. The only change was the speaker deciding to bring the package to a vote knowing that it would pass without majority GOP support – a violation of what’s been known as the Hastert rule.

I don’t have an easy explanation for why Johnson finally had a change of heart and was willing to risk his speakership for Ukraine aid. None of the current batch of explanations – Biden worked him over effectively, the classified intel was sobering, he doesn’t think MTG has the votes to oust him – is particularly convincing or satisfying.

Even if Johnson ended up doing the right thing and achieved a good outcome, it would be good to understand why! As Brian Beutler muses:

By way of analogy: If you drain your retirement savings to pay off the mob, but win it all back gambling, on one level it’s no harm no foul. On another level it raises some important questions about who you are!

Indeed.

You Come At The King, You Best Not Miss

Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) is still threatening to oust Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA), but notably she did not call for a vote on her motion to oust Johnson after the House passed the Ukraine aid package.

How Are Things Going Inside The House GOP?

Rep. Tony Gonzales (R-TX) tore into the House GOP’s far-right flank:

Ukraine Aid Passes!

The decade-plus internal House GOP squabble is of course mostly a sideshow to the real news that desperately needed military aid for Ukraine will now be available to try to counter the advantage Russia has pressed in the months that the critical aid has been delayed.

The aid package still must pass the Senate, but that is expected, and the military aid should begin flowing again soon after.

So This Happened

One of the weekend’s lowlights: Anti-Ukraine Republicans pretended to take great umbrage over members of Congress waving Ukraine flags on the House floor after the aid vote Saturday.

Trump Trial Begins In Earnest Today

Opening statements are expected to begin at 9:30 a.m. ET. We’ll have live coverage here.

David Pecker, the former publisher of The National Enquirer, is expected to be the first prosecution witness, according to the NYT. The trial will adjourn early for Passover, so it’s unclear how much of Pecker’s testimony we’ll get today.

A couple of reading assignments to catch yourself up:

- Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg’s statement of facts in the case.

- Joyce Vance previews opening statements.

Also Happening Today …

New York Judge Arthur Engoron will hear arguments over whether the $175 million appeal bond in the civil fraud case against Trump is sufficient.

Quote Of The Day

It can happen again. Extremism is alive and well in this country. Threats of violence continue unabated.

U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan of Washington, D.C., while handing down her harshest sentence to date for a Jan. 6 rioter

Another $4M In Legal Expenses Paid For By Donors

Trump’s campaign and various related committees spent another $4 million on legal expenses for Trump in March, according to the latest filings:

All told, Trump’s campaign and outside political groups have paid more than $66 million in legal-related costs since early 2023, according to a Wall Street Journal review of new campaign filings made public Saturday. That translates to about $145,000 a day.Trump campaign legal billsSource: Federal Election CommissionNote: Includes Trump’s campaign committee, SaveAmerica leadership PAC and the Trump SaveAmerica Joint Fundraising Committee.

King Of His Tiny Corner Of The Internet

WaPo: On Truth Socials, Trump “offers an intimate view of what his second term could look like: isolated, vitriolic and vengeful.”

2024 Ephemera

- Gov. Kristi Noem (R-SD) is tap-dancing around whether she supports exceptions to abortion bans for victims of rape or incest.

- NYT: The Trump campaign and the GOP plan to dispatch more than 100,000 volunteers and lawyers to monitor elections in battleground states, working in concert with conservative activists.

- PA-Sen: GOP Senate candidate David McCormick claims he grew up on a family farm, but the NYT’s reporting suggests he has given a misleading impression about key aspects of his background.

Passover Week Protests At Columbia

Columbia University is shifting to virtual classes on the first day of Passover after weekend protests over Gaza and antisemitic threats prompted a rabbi to urge Jewish students to return home and the White House to issue a statement condemning “physical intimidation targeting Jewish students and the Jewish community.”

IDF Intel Chief Resigns

The head of Israel’s Military Intelligence Directorate has resigned over the Oct. 7 Hamas attack.

AOC Comes Through Again

The fame and notoriety of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) can sometimes obscure how thoughtful and capable she actually is:

Do you like Morning Memo? Let us know!

Lawmakers Hope To Use This Emerging Climate Science To Charge Oil Companies For Disasters

This story first appeared at Stateline.

A fast-emerging field of climate research is helping scientists pinpoint just how many dollars from a natural disaster can be tied to the historic emissions of individual oil companies — analysis that is the centerpiece of new state efforts to make fossil fuel companies pay billions for floods, wildfires and heat waves.

When a flood or wildfire hits, researchers in “attribution science” run computer models to help determine whether the disaster was caused or intensified by climate change.

As those models become more precise, other scientists are working to measure how specific companies, such as Exxon Mobil or Shell, have contributed to climate change through their historic greenhouse gas emissions.

“This is a growing field, and it’s a game changer for addressing climate change,” said Delta Merner, the lead scientist for the Science Hub for Climate Litigation at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a climate-focused research and advocacy nonprofit. “It has a role to play in litigation and in policy, because it gives us that precision.”

For the first time, some state lawmakers are trying to turn that advanced modeling into policy. Under their proposals, state agencies would use attribution science to tally up the damages caused by climate change and identify the companies responsible. Then, they would send each company a bill for its portion of the destruction, from heat waves to hurricanes.

“This science is evolving rapidly,” said Anthony Iarrapino, a Vermont-based attorney and lobbyist for the Conservation Law Foundation who has been a leading advocate for attribution-based policy. “This is something that couldn’t have been done 10 years ago. [Lawmakers] are benefiting from this shift in focus among some of the most talented scientists we have out there.”

Lawmakers in Vermont and four other blue states have proposed “climate Superfund” bills, which would create funds to pay for recovery from climate disasters and preparation for sea level rise and other adaptation measures.

Oil and coal companies would pay into those funds based on the percentage of emissions they’ve caused over a set period. The legislation’s name references the 1980 federal Superfund law that forces polluters to pay for the cleanup of toxic waste sites.

This is a growing field, and it’s a game changer for addressing climate change. It has a role to play in litigation and in policy, because it gives us that precision.

— Delta Merner, lead scientist for the Science Hub for Climate Litigation at the Union of Concerned Scientists

States’ climate proposals come after years of lawsuits by state attorneys general against many of those same companies. They claim the companies knew years ago that fossil fuel use was causing climate change, but misled the public about that danger. While the courtroom fights are far from resolved, some advocates think it’s time for lawmakers to get involved.

“There have been a lot of lawsuits trying to get these companies to pay for some damages, and the industry’s message has been, ‘This is a task for legislatures, not the courts,’” said Justin Flagg, director of environmental policy for New York state Sen. Liz Krueger, a Democrat. “We are taking up that invitation.”

Oil industry groups object to the methodologies used by attribution scientists. Industry leaders say lawmakers are acting out of frustration that the lawsuits have been slow to progress.

“The science isn’t proven,” said Mandi Risko, a spokesperson for Energy In Depth, a research and public outreach project of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, a trade group. “[The state bills] are throwing spaghetti at a wall. What’s gonna stick?”

Oil companies also assert that climate Superfund bills, if enacted, would force the penalized companies to raise gas prices on consumers in those states.

A legislative push

The push for climate Superfund legislation began with a federal bill in 2021, backed by U.S. Senate Democrats, that failed to pass. Lawmakers in a handful of states introduced their own proposals in the following years. Now, Vermont could soon become the first to enact a law.

Vermont’s measure would task the state treasurer with calculating the costs of needed climate adaptation work, as well as the damage inflicted by previous disasters such as last summer’s devastating floods.

The program would collect money from companies that emitted more than 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide around the world from 1995 to the present day. Those companies with a certain threshold of business activity in Vermont would be charged according to their percentage of global emissions.

“We can with some degree of certainty say how much worse these storms are [due to climate change],” said Democratic state Sen. Anne Watson, the bill’s sponsor. “That really is the foundation for us to bring a dollar value into a piece of legislation like this.”

Environmental advocates say the bill is a pioneering attempt to use the latest science for accountability.

“This is one of the first instances of climate attribution science being at the center of legislation,” said Ben Edgerly Walsh, climate and energy program director with the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, an environmental nonprofit. “That reflects the maturity of this field.”

Walsh said the measure, if passed, is expected to bring in hundreds of millions of dollars. The bill was approved by the Senate earlier this month in a 26-3 vote, and a House version has been co-sponsored by a majority of that chamber’s members. Republican Gov. Phil Scott has not said whether he would sign it into law, but he has said he would prefer to see larger states go first.

Exxon Mobil deferred an interview request to the trade group American Petroleum Institute. The institute did not grant an interview with Stateline, but pointed to the comments it filed with Vermont lawmakers last month. The group said its members lawfully extracted fossil fuels to meet economic demand and should not be punished for that after the fact. The letter also questioned states’ authority to impose payments for emissions that were generated overseas.

Meanwhile, New York lawmakers are currently negotiating a budget that could include a climate Superfund policy. A measure that passed the Senate at the end of last year would seek to collect $75 billion over 25 years to pay for the damages of climate change.

“It’s not intended to be punitive, it’s intended to pay for our needs,” said Flagg, the New York Senate staffer. “It’s going to be a lot of money, and $75 billion is only a small portion of that.”

The proposal applied to companies with a presence in New York responsible for more than 1 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide between 2000 and 2018.

In Massachusetts, Democratic state Rep. Steve Owens introduced a similar bill last year. While the measure failed to advance, Owens said lawmakers are becoming familiar with the concept.

“Is this fraud that we can litigate or something that we can legislate?” he asked. “That question was not settled in time for this session. We’re going to keep working to get people used to the idea.”

Lawmakers in California and Maryland also have introduced climate Superfund bills this session.

Challenges ahead

If legislatures in Vermont and elsewhere pass climate Superfund bills, the state officials who carry them out are expected to rely heavily on researcher Richard Heede’s “Carbon Majors” project, which has tallied the historic emissions of 108 fossil fuel producers using public data.

“We know enough to attribute temperature response, sea level rise, build a reasonable case and apportion responsibility among the major fossil fuel producers,” said Heede, whose project is part of the Climate Accountability Institute, a Colorado-based nonprofit research group that has received funding from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. “But that hasn’t been tested in court.”

Heede said that more than 70% of carbon emissions from fossil fuels can be linked to just over 100 companies, but noted that many large emitters, such as Saudi Aramco, the national oil company of Saudi Arabia, are owned by international governments that are unlikely to face accountability from U.S. state governments.

Last year, a study looking at temperature and water vapor data found that much of the area burned by wildfires in the West over the past several decades was tied to emissions produced by the largest fossil fuel and cement companies. That research by the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Merner and others was published in Environmental Research Letters. Similar research, looking at storms and heat waves, can show how much of an event’s intensity and economic damage can be pinned on climate change.

Backers of the state bills say they expect strong legal challenges from oil companies if their proposals become law. Pat Parenteau, an emeritus professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School, has supported states’ climate lawsuits, but cautioned that climate Superfund bills will likely face similar legal delays if enacted.

“The companies are gonna litigate the hell out of it,” he said. “Throw something more at them, but don’t for a minute think there’s something magical about it.”

He urged Vermont to wait for bigger states, such as New York, to pass the first climate Superfund bills and face the ensuing legal onslaught.

Advocates acknowledged the bill will face legal challenges, but said that’s not a reason to pause their efforts.

“Vermont is already paying through the nose for the climate crisis,” Walsh said. “The sooner we pass a law like this, the sooner we could actually see these companies be held financially accountable.”

This story first appeared at Stateline and is reprinted here through a Creative Common license. Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org. Follow Stateline on Facebook and Twitter.

A Few More Notes on Israel and Iran

Let me return to add a few more thoughts on what happened between Israel and Iran. Iran launched a massive fusillade of drones and missiles, but virtually none of them got through. A few days later Israel retaliated with a much smaller volley, which was apparently just a handful of drones that were launched from aircraft just outside of Iranian airspace. They were targeted at Isfahan, which is where Iran’s nuclear facilities are located, but were aimed apparently at a drone factory there. Iran not only hasn’t responded but has mostly pretended that it didn’t even happen, at least for domestic audiences. So Israel responded but at least for now they seem to have been able to do so and have the Iranians call things even.

Continue reading “A Few More Notes on Israel and Iran”Does Asking Americans Whether ‘The Country Is On The Wrong Track’ Actually Measure Anything Useful?

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

If you pay any attention to politics and polling, you have likely heard that your friends and neighbors are not very happy with the direction of the country. You might not be, either.

One ABC News/Ipsos survey in November 2023 showed three-quarters of Americans believed the country was on the “wrong track.” Only 23% believed it was headed in the “right direction.”

And the survey was not an outlier. Poll after poll shows a sizable majority of the nation’s residents disapprove of its course.

Have Americans — long seen as upbeat, can-do optimists — really grown dour about the state of the nation and where it’s headed?

The answer, we think, is yes and no. Or, to be more direct, as the researchers who run the American Communities Project, which explores the differences in 15 different types of community in the United States, we believe the surveys are asking a question with no real meaning in the United States in 2024 — a question that may have outlived its usefulness.

An ‘astonishing finding’

“Do you feel things in the country are generally going in the right direction, or do you feel things have gotten off on the wrong track?”

That question or one very much like it is well known to anyone who has glanced at a poll story or studied the data of a survey in the past 50 years.

These public opinion surveys, often sponsored by news organizations, seek to understand where the public stands on the key issues of the day. In essence, they tell the public about itself. Political parties and candidates often conduct their own surveys with a version of the “right direction/wrong track” question to better understand their constituencies and potential voters.

The American Communities Project, based at Michigan State University, uses demographic and socioeconomic measures to break the nation’s 3,100 counties into 15 different types of communities — everything from what we label as “big cities” to “aging farmlands.” In our work with the project, we’ve found a strong reason to be skeptical of the “right direction/wrong track” question. Simply put, the divisions in the country have rendered the question obsolete.

In 2023, we worked with Ipsos to survey more than 5,000 people across the country in all those community types. We asked the survey participants what issues they were concerned about locally and nationally. How did they feel about the Second Amendment? About gender identity? About institutional racism? We found a lot of disagreement on those and other controversial issues.

But there were also a few areas of agreement. One of the big ones: In every community we surveyed, at least 70% said the country was on the “wrong track.” And that is an astonishing finding.

Agreement for different reasons

Why was that response so surprising?

The community types we study are radically different from each other. Some are urban and some are rural. Some are full of people with bachelor’s degrees, while others have few. Racially and ethnically, some look like America as it is projected to be in 30 years — multicultural — and some look like the nation did 50 years ago, very white and non-Hispanic. Some of the communities voted for President Joe Biden by landslide numbers in 2020, while others did the same for Donald Trump.

Given those differences, how could they be in such a high level of agreement on the direction of the country?

To answer that question, we visited two counties in New York state in January that are 3½ hours and several worlds away from each other: New York County, which is labeled a “big city” in our typology and encompasses Manhattan, and Chenango County, labeled “rural middle America” in our work, located in the south-central part of the state.

In 2020, Biden won 86% of the vote in big metropolitan Manhattan, and Trump won 60% in aging, rural Chenango.

When we visited those two counties, we heard a lot of talk of America’s “wrong track” in both places from almost everyone. More important, we heard huge differences in “why” the country was on the wrong track.

“If something don’t change in the next election, we’re going to be done. We’re going to be a socialist country. They’re trying to tell you what you can do and can’t do. That’s dictatorship, isn’t it? Isn’t this a free country?” said James Stone, 75, in Chenango County.

Also in Chenango County, Leon Lamb, 69, is concerned about the next generation.

“I’m worried about them training the kids in school,” he said. “You got kids today who don’t even want to work. They get free handouts … I worked when I was a kid … I couldn’t wait to get out of the house. I wanted to be on my own.”

In New York City, meanwhile, Emily Boggs, 34, a theater artist, bartender and swim instructor, sees things differently as she struggles to make ends meet.

“We’ve been pitched since we were young, that like, America is the best country in the world. Everyone wants to be here, you’re free, and you can do whatever you want,” Boggs said. “And it’s like, well, if you have the money … I’ve got major issues with millionaires and billionaires not having to pay their full share of taxes, just billionaires existing … It’s the inequality.”

A lifelong New York City resident, Harvey Leibovitz, 89, told us: “The country is on the wrong direction completely. But it’s based upon a very extreme but significant minority that has no regard to democracy, and basically, in my opinion, is racist and worried about the color of the population.”

Opposite views in same answer

To be clear, we are not saying that asking people about the direction of the country is completely worthless. There may be some value in chronicling Americans’ unhappiness with the state of their country, but as a stand-alone question, “right direction/wrong track” is not very helpful. It’s the beginning of a conversation, not a meaningful measure.

It turns out that one person’s idea about the country being on the wrong track may be completely the opposite of another person’s version of America’s wrong direction.

It’s easy to grasp the appeal of one broad question aimed at summarizing people’s thoughts. But in a complicated and deeply fragmented country, a more nuanced view of the public’s perceptions of the nation would help Americans understand more about themselves and their country.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

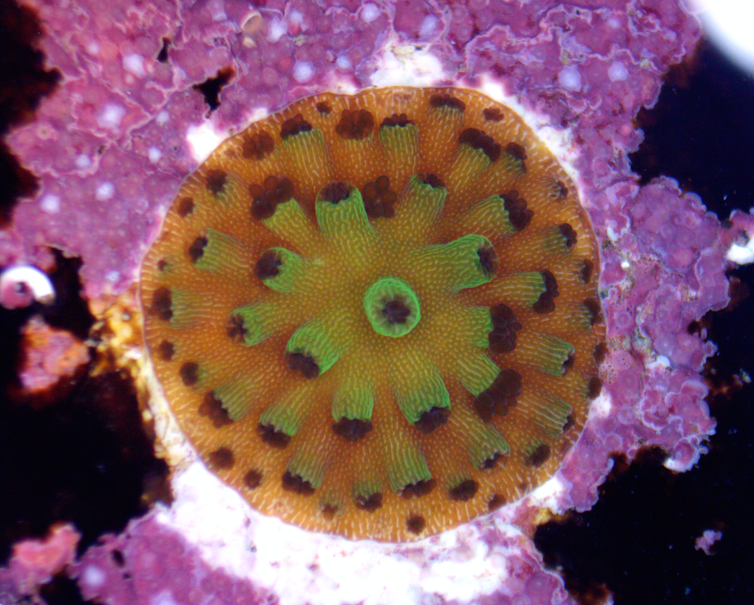

As Climate Change Imperils Coral Reefs, Scientists Are Deep-Freezing Corals To Repopulate Future Oceans

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

Coral reefs are some of the oldest, most diverse ecosystems on Earth, and among the most valuable. They nurture 25% of all ocean life, protect coasts from storms and add billions of dollars yearly to the global economy through their influences on fisheries, new pharmaceuticals, tourism and recreation.

Today, the world’s coral reefs are degrading at unprecedented rates due to pollution, overfishing and destructive forestry and mining practices on land. Climate change driven by human activities is warming and acidifying the ocean, triggering what could be the largest coral bleaching event on record. Under these combined pressures, scientists project that most corals could go extinct within a few generations.

I am a marine biologist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. For 17 years, I have worked with colleagues to create a global science program called the Reef Recovery Initiative that aims to help save coral reefs by using the science of cryopreservation.

This novel approach involves storing and cooling coral sperm and larvae, or germ cells, at very low temperatures and holding them in government biorepositories.

These repositories are an important hedge against extinction for corals. Managed effectively, they can help offset threats to the Earth’s reefs on a global scale. These frozen assets can be used today, 10 years or even 100 years from now to help reseed the oceans and restore living reefs.

Safely frozen alive

Cryopreservation is a process for freezing biological material while maintaining its viability. It involves introducing sugarlike substances, called cryoprotectants, into cells to help prevent lethal ice formation during the freezing phase. If done properly, the cells remain frozen and alive in liquid nitrogen, unchanged, for many years.

Many organisms survive through cold winters in nature by becoming naturally cryopreserved as temperatures in their habitats drop below freezing, Two examples that are common across North America are tardigrades — microscopic animals that live in mosses and lichens — and wood frogs.

Today, coral cryopreservation techniques rely largely on freezing sperm and larvae. Since 2007, I have trained many colleagues in coral cryopreservation and worked with them to successfully preserve coral sperm. Today we have sperm from over 50 species of corals preserved in biorepositories worldwide.

We have used this cryopreserved sperm to produce new coral across the Caribbean via a selective breeding process called assisted gene flow. The goal was to use cryopreserved sperm and interbreed corals that would not necessarily have encountered each other — a type of long-distance matchmaking.

Genetic diversity is maintained by combining as many different parents as possible to produce new sexually produced offspring. Since corals are cemented to the seabed, when population numbers in their area decline, new individuals can be introduced via cryopreservation. The hope is that these new genetic combinations might have an adaptation that will help coral survive changes in future warming oceans.

These assisted gene flow studies produced 600 new genetic-assorted individuals of the threatened elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. As of early 2024, there are only about 150 elkhorn individuals left in the wild in the Florida population. If given the chance, these selectively bred corals held in captivity could significantly increase the wild elkhorn gene pool.

Preserving sperm cells and larvae is an important hedge against the loss of biodiversity and species extinctions. But we can only collect this material during fleeting spawning events when corals release egg and sperm into the water.

These episodes occur over just a few days a year — a small time window that poses logistical challenges for researchers and conservationists, and limits the speed at which we can successfully cryo-bank coral species.

To complicate matters further, warming oceans and increasingly frequent marine heat waves can biologically stress corals. This can make their reproductive material too weak to withstand the rigors of being cryopreserved and thawed.

Scaling up the rescue

To collect coral material faster, we are developing a cryopreservation process for whole coral fragments, using a method called isochoric vitrification. This technique is still developing. However, if fully successful, it will preserve whole coral fragments without causing ice to form in their tissues, thus producing viable fragments after they’ve thawed that thrive and can be placed back out on the reef.

To do this, we dehydrate the fragment by exposing it to a viscous cryoprotectant cocktail. Then we place it into a small aluminum cylinder and immerse the cylinder in liquid nitrogen, which has a temperature of minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 196 Celsius).

This process freezes the cylinder’s contents so fast that the cryoprotectant forms a clear glass instead of allowing ice crystals to develop. When we want to thaw the fragments, we place them into a warm water bath for a few minutes, then rehydrate them in seawater.

Using this method, we can collect and cryopreserve coral fragments year-round, since we don’t have to wait and watch for fleeting spawning events. This approach greatly accelerates our conservation efforts.

Protecting as many species as possible will require expanding and sharing our science to create robust cryopreserved-and-thawed coral material through multiple methods. My colleagues and I want the technology to be easy, fast and cheap so any professional can replicate our process and help us preserve corals across the globe.

We have created a video-based coral cryo-training program that includes directions for building simple, 3D-printed cryo-freezers, and have collaborated with engineers to develop new methods that now allow coral larvae to be frozen by the hundreds on simple, inexpensive metal meshes. These new tools will make it possible for labs around the world to significantly accelerate coral collection around the globe within the next five years.

Safeguarding the future

Recent climate models estimate that if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, 95% or more of the world’s corals could die by the mid-2030s. This leaves precious little time to conserve the biodiversity and genetic diversity of reefs.

One approach, which is already under way, is bringing all coral species into human care. The Smithsonian is part of the Coral Biobank Alliance, an international collaboration to conserve corals by collecting live colonies, skeletons and genetic samples and using the best scientific practices to help rebuild reefs.

To date, over 200 coral species, out of some 1,000 known hard coral species, and thousands of colonies are under human care in institutions around the world, including organizations connected with the U.S. and European arms of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Although these are clones of colonies from the wild, these individuals could be put into coral breeding systems that could be used for later cryopreservation of their genetically-assorted larvae. Alternatively, their larvae could be used for reef restoration projects.

Until climate change is slowed and reversed, reefs will continue to degrade. Ensuring a better future for coral reefs will require building up coral biorepositories, establishing on-land nurseries to hold coral colonies and develop new larval settlers, and training new cryo-professionals.

For decades, zoos have used captive breeding and reintroduction to protect animals species that have fallen to critically low levels. Similarly, I believe our novel solutions can create hope and help save coral reefs to reseed our oceans today and long into the future.

This article has been updated to include the development of a global-scale coral bleaching event in the spring 2024. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.