This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

Democracy poses a dilemma where matters of professional expertise come into play, and the recent MAGA assault on public education, trans youth, sex education and the LBGTQ community broadly has forced local school boards to serve as a petri dish for handling that dilemma.

On the one hand, the essence of democratic self-government is open deliberation to hash out questions on which public sentiment is divided. In this spirit, all it takes is pressure from impassioned citizens to get an issue onto the political agenda for elected officials to decide. Ultimately, the debate and deliberation process is what lends democratic legitimacy to such decisions.

On the other hand, should the public square be open to any and all issues that a set of community members might push? Are there other considerations that argue for keeping some questions out of the political process? For instance, much of the day-to-day public sector work is done by trained professionals, like the teachers and librarians in public schools. Does it make sense, for instance, to have members of the public decide which books should be removed from school libraries? Then there’s the matter of basic rights and freedoms and protection from discrimination. Certainly these shouldn’t be up for debate.

Having spent my entire career as a professional policy advocate — working for advocacy groups and foundations and then becoming a consultant evaluator of such work — I’m fascinated by the interplay of public debate, politics, and governmental decision making. In these battles over protecting the safety and rights of transgender kids, we’re confronted with the politics of questions that shouldn’t be political.

As the extreme right wing has stoked a moral panic about transgender people, local activists and self-styled parental rights groups have made this dilemma all too real for public schools around the country. The Linn-Mar School District in Marion, Iowa is a case in point.

By the time the Linn-Mar School Board in Marion, IA voted to approve gender-affirming policies for trans students in April 2022, the school district had already been abiding by those policies for five years. Those guidelines had worked quite well for the district and board members had to decide if it was really necessary for their body to ratify the policy. Arguably it might be best to just let the school district superintendent and staff keep implementing gender-affirming practices throughout the district without a lot of political back-and-forth. But after hearing local demands for greater transparency—and seeing another Iowa school board in Urbandale formally adopt a policy to protect trans students—Linn-Mar school board members added the issue to their public agenda.

In the ensuing public debate, board members continued to navigate tricky questions about the relationship between politics, professionalism, and basic rights. The Linn-Mar School Board fight was one of eight local controversies included in research on local politics I did with my fellow evaluator of policy change efforts Kathleen Sullivan. Our “They Said, We Said” study focused on messaging and issue-framing in what we termed the “close-quarters public square” of local government and politics. We looked at local advocates’ successes in countering some of the right-wing issue frames that are more firmly entrenched at the state and national levels. And for the Linn-Mar trans student policy case, Linn-Mar School Board Member Rachel Wall shared with us her first-hand account of the political battle.

As a matter of both policy and politics, the Linn-Mar District took its cues from the law. Its procedures for transgender students were devised in line with civil rights laws barring discrimination on the basis of gender or gender identity. School district policy supported trans students’ use of gender-affirming restrooms, pronouns, and hotel rooms on school trips — all of which were already working as intended and without incident.

Between the policy’s success and existing laws, most Linn-Mar School Board members saw no other course than the one they were already on. In public discussions, the five supportive board members (out of seven) stressed that the policy was their only lawful option.

In Kathleen and my interview with Board Member Wall, she highlighted the nonpartisan nature of school board elections as well as the heightened political pressures, which surged during COVID. The Board’s experience with anti-mask and anti-vax forces were front-of-mind as they dealt with mounting attacks on trans students in the school district:

“The mask situation, the vaccination situation had kicked up so much vitriol and so politicized the board that we tried to frame it in a way that was apolitical,” she said.

In line with their decision to stand firm on their legal duties and stay above the fray, the school board majority refrained from counterbalancing their right wing critics politically. As shown by the comments at the board’s climactic April 2022 public hearings, opponents and anti-trans activists echoed fears expressed elsewhere around the country about parents being excluded from trans students’ gender support plans and posed hypotheticals about abuse in bathrooms and locker rooms. And in an echo of the familiar “reverse racism” fallacy, they complained that transgender students were being given greater rights at the expense of the cis-gender majority.

In response, an educator who’d worked in the Linn-Mar schools for 35 years voiced her concern that misplaced fears have shifted focus away from real dangers. She pointed out that abuse of young people is committed all too frequently by clergy, coaches, teachers, or relatives, while trans student misconduct in bathrooms or locker rooms is more phantom than reality. To protect the safety of trans students, the school’s plans for those students indeed excluded their parents for any students who don’t feel safe at home. Because no parent has a right to be abusive. One of the trans students at the school board hearing testified about the steady stream of bigotry and jeering they receive from other students during the school day.

The District’s own survey of students found that gender non-conforming students were more than twice as likely to have experienced bullying (approximately half versus one-fifth). The study also found that far fewer gender queer students felt safe or comfortable sharing at school (fewer than half), compared with cis-gender students. With that said, one trans student who’d been having a difficult time beginning their gender transition within the past year told the school board about something that’s helped make it a little easier: the support of the school administration and board itself.

Again, Linn-Mar’s trans student policy had already been in place for five years when the school board opened it up for formal debate and decision. So while board member proponents tried to avoid a political debate and simply stick to laws against discrimination, they gave space for the other side’s political pot-stirring to speak for itself—a repeat of the earlier mask mandate controversy.

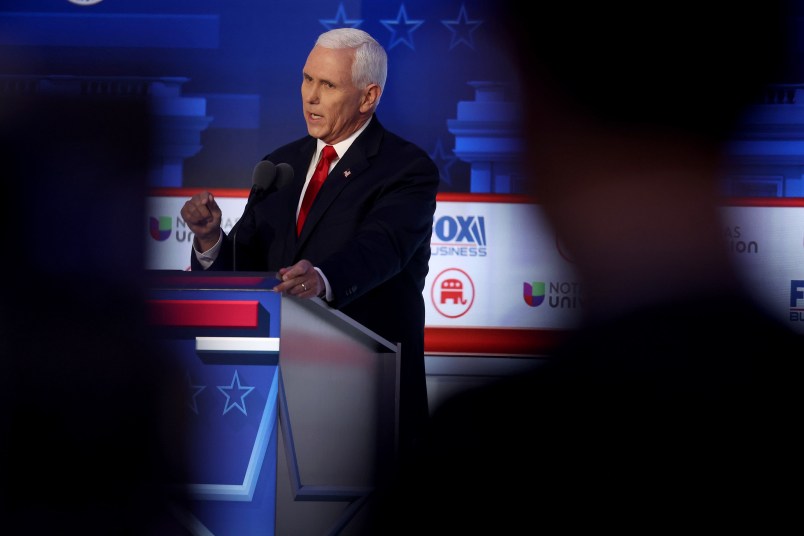

Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds and former Vice President Mike Pence seized on reports of the public debate and used Linn-Mar to score political points. On the campaign trail in nearby Cedar Rapids in February 2023, the former vice president commented, “No one should have a greater role over what our children are learning or the values they’re being taught than their parents.” Eight months later during a Republican primary debate, Pence slammed Linn-Mar District by name and misleadingly said the schools would withhold students’ “gender transition plans” from parents. In reality, gender support plans to affirm students’ gender identities at school are quite different from any medical plan for actual gender transition.

And in our interview with Board Member Rachel Wall, she stressed that it’s “not a political issue,” emphasizing the district’s educational mission and the various measures they take to meet student needs:

“We do that all the time. Think about all the ways in which we individualize education to meet the needs of students who have IEPs, students who have 504 plans, students who have behavioral issues,” she said. “We try to provide every student with an education that best fits them so they can do the best they can do academically, socially, emotionally.”

For her part, Governor Reynolds met privately with Linn-Mar parents opposed to gender support soon after the school board’s 2022 decision. And the governor followed up the next spring by pushing through a new state law restricting schools’ trans-supporting policies — and forcing Linn-Mar to make adjustments in order to comply. Among the new law’s provisions: a requirement to notify parents if a student asks for different pronouns to be used. In terms of Kathleen and my study comparing local politics to higher levels, the school board’s success in fending off right-wing pressures ultimately was trumped by state-level politics where far-right issue framing is harder to overcome.

Our report on issue frames in local controversies found that the trans students of Linn-Mar District have been well served by the professionalism of the district’s staff and support of the school board. The question remains, as Board Member Wall told us, of whether politics will someday strip away their support and protection. Will the self-styled defenders of parents’ rights continue to be a very vocal minority, or will they make good on their threats to get their own candidates onto school boards across the nation?

This school board debate over how to handle trans students is exactly why people of good will need to become and stay involved in local politics. If they don’t the bullies and haters will be unopposed and a lot of students will be hurt.

All of the influences of modern life work against people of good will becoming and staying involved. It takes an exceptional person to run for the local school board with the goal of actually helping kids grow up to be educated and responsible adults.

For democracy to work you need to have people making arguments in good faith.

The problem with this and other “hot button” issues is that there are politicians on the right who are bad faith actors, creating moral panics out of nothing but their need to distract voters from the lack of substance of their policies (or the fact that their policies are actually about helping the wealthy).

You can’t argue with bad-faith actors. And that’s the problem with this and other “culture war” issues.

It does create a dilemma for good-faith actors like this school board with no easy answer. But we’d be better off if the media called out the politicians who are bad-faith actors by fact-checking aggressively at a minimum…

This kind of ‘misinformation,’ particularly from the paranoid political Right, is a consistent feature of these political conflicts: when basic facts are distorted and denied, if you can’t even agree on what those facts are as Jon Stewart famously pointed out while roasting Bill O’Reilly as the Mayor of Bullshit Mountain, then problem solving is blocked at the very beginning.

“If we are to have another contest in the near future of our national existence, I predict that the dividing line will not be Mason and Dixon’s but between patriotism and intelligence on the one side, and superstition, ambition and ignorance on the other.” – Ulysses S. Grant

You know a political party is weak when it has to condone terrorizing and abusing children for its political points.

How insecure does your own masculinity have to be to panic over a trans kid at school?

(The “Party of Individual Freedom” sure spends a lot of time trying to regulate other people’s genitalia.)