Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), a prominent, progressive member of Congress long assumed to be eyeing a Senate run, said on Sunday that he won’t mount a bid for retiring Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s seat and will instead endorse Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA).

Continue reading “The California Primary Takes A Clearer Shape”The Labor Movement Has Found A Strategic Advantage In The Airline Industry

In the early morning hours of Jan. 11, a hack shut down the FAA’s systems, grounding all flights nationwide. I had a flight that morning to Minneapolis–St. Paul with a tight connection to Boise, Idaho. Once the ground stop was lifted, my Delta flight left New York’s LaGuardia.

Continue reading “The Labor Movement Has Found A Strategic Advantage In The Airline Industry “Meet Some Of Trump’s Guilty Friends

Join us on this walk down memory lane…

Michael Cohen

Trump Pardon? No. Definitely not.

(Photo by Yana Paskova/Getty Images)

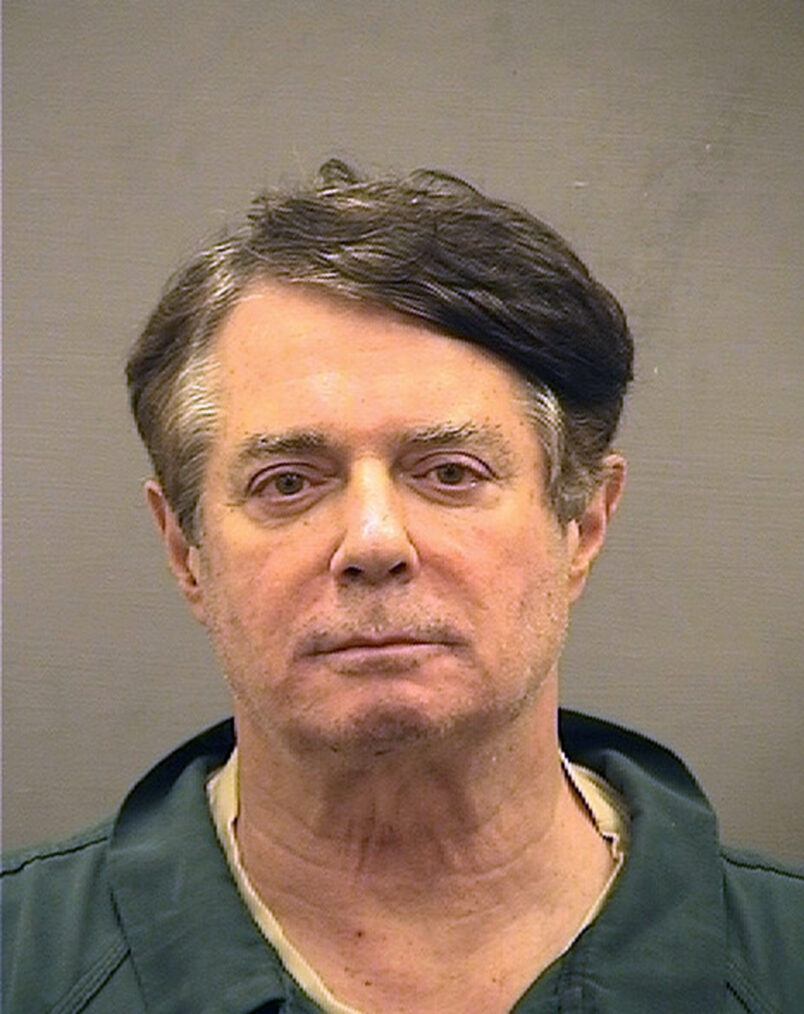

Paul Manafort

Trump Pardon? Yes.

(Photo by Alexandria Sheriff’s Office via Getty Images)

Allen Weisselberg

Trump Pardon? Wasn’t available.

(Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

Trump Pardon? Yes.

(Photo by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for Pepperdine University)

Steve Bannon

Trump Pardon? You bet.

(Photo by Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Michael Flynn

Trump pardon? Yes.

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Trump Pardon? No, but Alan Dershowitz reportedly pushed for one.

(AP Photo)

Rick Gates

(Photo By Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

The Trump Organization

Trump Pardon? N/A

(Photo by Epics/Getty Images)

Roger Stone

Trump Pardon? Yes.

(Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images)

George Papadopoulos

Trump Pardon? Yes.

(Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP/Getty Images)

Mississippi Has Invested Millions of Dollars to Save Its Oysters. They’re Disappearing Anyway.

This article was co-published by ProPublica and the Biloxi Sun Herald. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

By 2015, it was clear that Mississippi oysters were in crisis. It was a devastating development for the state: As late as 2009, the oyster industry had contributed an estimated $24 million in sales to the state’s economy, and it sustained 562 full- and part-time jobs.

Then-Gov. Phil Bryant convened an oyster council to come up with solutions.

“This is the soybean of the sea,” Bryant said at a community gathering in 2015 at which he unveiled the council’s report. “We’re going to make sure everyone enjoys it.” The council set a goal of producing 1 million sacks of oysters a year by 2025.

But almost a decade later, that goal is nowhere in sight: In a region that helped pioneer the oyster industry, only 457 sacks were harvested in 2022, none of them from the public reefs that the state had worked to restore.

A lot has gone wrong for oysters here, where the region’s blend of saltwater and freshwater has historically nurtured them. Brutal storms and federal flood-management protocols that send freshwater flowing into oyster habitats have both taken their toll, and have escalated as a result of climate change.

But new reporting from ProPublica and the Sun Herald shows that the state has also failed to stem the crisis, investing millions of dollars to rebuild reefs in ways that did not respond to changing conditions. Some of that money came from funds the state received as a result of the BP oil spill.

“They’re just wasting money,” said Keath Ladner, a former oyster fisherman whose family was in the seafood business for three generations. “And the fishermen know this.”

For decades, the state has focused on rebuilding reefs, restoring them with shell or rock to give baby oysters a place to settle and grow. Since Hurricane Katrina damaged or destroyed more than 90% of state reefs in 2005, two state agencies have spent $55 million to restore Mississippi Sound oysters, which are critical to the estuary’s health.

Mississippi maintains the majority of the state’s reefs, opening them to licensed fishermen for harvest. But reefs maintained by the state have shrunk: The state estimates that the Mississippi Sound historically had about 12,000 acres of oyster reefs, compared to 8,112 acres today. There hasn’t been a harvest on Mississippi’s public reefs since 2018. Fishermen have left the industry in droves.

Locals in the fishing industry say the state has failed to do routine maintenance, which includes planting rocks or shells on solid ground and later turning or raking them to knock off silt so baby oysters can settle there.

Joe Spraggins, executive director of the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources, which regulates and oversees the state’s oysters, said his agency does not have enough money and personnel to maintain oyster reefs in today’s climate.

Spraggins himself acknowledged the high costs and poor outcomes. “I could probably go buy 100,000 sacks of oysters in Texas every year and give them to y’all to sell and come out cheaper,” he told oystermen at a meeting in the fall of 2021. He thinks private operators could expand oyster reefs beyond the acres that the Marine Resources Department plants with rock and tries to maintain.

That’s the conclusion of state Sen. Mike Thompson, an attorney who piloted offshore boats when he was younger. In his opinion, it’s time to give “the fishermen who know and understand the fishery the opportunity to restore the reefs.” He recently introduced legislation that would expand private leasing of oyster grounds.

The sense of urgency about saving the oysters stems from more than falling seafood sales. Oyster reefs are critical for the health of the Mississippi Sound and other estuaries. They serve as nurseries, refuge and foraging grounds for many aquatic animals, including fish, shrimp and crabs. They protect the shoreline from erosion in storms. And oysters filter and clean the water as they feed, with one oyster capable of filtering up to 50 gallons a day.

“That is a keystone species for any estuary, and that’s exactly what we have here in the Mississippi Sound,” said Erik Broussard, deputy director of marine fisheries for the Marine Resources Department. “So it’s extremely important for everything that inhabits the Mississippi Sound to have a healthy shellfish population.”

A global analysis published in 2009 concluded that “oyster reefs are one of, and likely the most, imperiled marine habitat on earth. The oyster fisheries of the Gulf of Mexico need to be managed for what they represent: likely the last opportunity in the world to achieve both large-scale reef conservation and sustainable fisheries.”

But signs of recovery are hard to find in this Gulf of Mexico estuary. On a sunny day in October aboard a fishing boat called the Salty Boy, coastal science professor Eric Powell and crew scoured the bottom of the western Mississippi Sound for oysters.

Over six hours, they found only five live adult oysters large enough to be harvested. Powell was encouraged to see more young oysters growing on the reefs, but said the population is still “well short” of recovery.

Years of Decline

The Jenkins family ran a seafood business on the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia until disease ravaged the oyster beds there.

By the 1990s, they were buying their oysters from Mississippi, which had been a major seafood producer since the early 20th century: Oyster shells paved the beach highway and seafood factories once lined the shores in Biloxi, where casinos dominate the commercial waterfront today.

So the Jenkins family followed the oysters to Pass Christian, on the western side of the Mississippi Sound, a Gulf of Mexico estuary where saltwater from the Gulf mixes with freshwater from rivers and other sources. The family found a fleet of around 100 oyster boats docked in the harbor to supply their new company, Crystal Seas Seafood. Business was good.

“My dad worked there all day long during oyster season, helping unload the boats for us and load the trucks for us and some of our customers,” Jennifer Jenkins said.

Today, however, most of the oyster boats in Pass Christian’s harbor have been sold or re-fitted for crabbing or shrimping. In 2004, the state had 13 companies licensed to process oysters. By 2022, there were only three, state records show.

“Oysters, it’s shot,” said Roscoe Liebig, a former oyster fisherman who runs a live bait shop from a steel barge in Pass Christian’s harbor. “They’re finding a few here and a few there, but it’s mainly just petrified shells.”

The region’s reefs have taken dramatic hits in the last two decades, triggering mass oyster deaths. The first blow was Hurricane Katrina, the August 2005 storm that scoured reefs and buried oysters in mud. The Marine Resources Department estimated that 90% of reefs were damaged or destroyed.

The storm also devastated local infrastructure. Keath Ladner’s grandfather had opened a seafood market in the region in 1942, serving the picturesque city of Bay St. Louis, which drew tourists and New Orleans residents who built second homes along the shorelines.

The business eventually expanded to Bayou Caddy in Hancock County, which borders Louisiana. There, Ladner’s father operated a seafood and ice business with docks where the family bought and sold oysters and shrimp. Ladner and his brother followed his father into the business, expanding with a marina.

Ladner said his family lost $8 million in buildings and equipment to Katrina. The story of loss was common along the 70 miles of Mississippi coastline pummeled by the hurricane’s storm surge, which reached up to 28 feet.

The oyster population suffered again five years later, when oil gushed from a BP well in the Gulf for 87 days, fouling 1,300 miles of coastline from Texas to Florida and killing sea turtles, dolphins and birds.

As damage from the oil spill was still being assessed, the Army Corps of Engineers opened the Bonnet Carré Spillway in May 2011 for 42 days to prevent Mississippi River flooding. The spillway empties river water into Lake Pontchartrain, in Louisiana, which flows into the Mississippi Sound. Opening that waterway follows federal protocols for preventing flooding in the region, but doing so can reduce salinity in nearby waterways to levels at which oysters are unable to survive. The 2011 opening killed 85% of oysters in the Mississippi Sound.

The struggling oyster population took another hit in 2016, when many were killed by low oxygen levels. The hypoxia event is unexplained, but not uncommon in the Sound, said Powell, the coastal scientist.

But as disasters go, it was the huge quantity of freshwater released by the Bonnet Carré Spillway in 2019 that topped them all. The spillway was opened twice, for a record-high total of 123 days, because of severe Mississippi River flooding caused by heavy rainfall. The river water killed almost all the oysters in the western Sound and, for the first time in memory, Spraggins of Marine Resources said, killed oysters all the way to Pascagoula, more than 100 nautical miles away, near the Alabama state line.

As climate change ushers in more intense rainfall, one 2020 paper from University of Mississippi scientists suggested that the continued reliance on this method of preventing floods could render oyster harvesting unsustainable in the western Sound.

“If the decision is, ‘We’re going to depend totally on that one spillway, which means that periodically Mississippi Sound is going to become a freshwater lake,’ then let’s not worry about spending a lot of money trying to restore oyster reefs because you’re just pouring money down a rathole,” Powell said.

Failed Interventions

Oysters reproduce by releasing sperm and eggs into the water during spawning season, which in the Mississippi Sound occurs between May and October. These larvae float freely for two to three weeks before cementing for life to a hard surface.

But as reefs disappear, hard surfaces can be difficult to find. So as the disasters in the Sound escalated, Mississippi poured millions of dollars into physically rebuilding the reefs that oysters need to grow.

Since 2005, Mississippi’s Department of Marine Resources has spent $35.6 million on oyster restoration. And after a federal settlement with BP over its oil spill sent money for economic development and environmental restoration to the region, the state’s Department of Environmental Quality has spent another $19.8 million on the effort.

One $10 million project that the Environmental Quality and Marine Resources departments carried out a decade ago involved spraying limestone mixed with a small quantity of oyster shell from a barge onto 12 western Sound reefs covering 1,430 acres.

The majority of the material was sprayed in spring 2013. A 2016 monitoring report filed by Marine Resources found that on five of those reefs, between 30% and 90% of the material sprayed sank into the mud, where oysters are unable to grow.

A final report filed on the project in July 2021 tells the story: zero adult oysters found in samples from the 12 sites sprayed.

“It’s very unfortunate that our goal was not met,” the report concludes. “Natural Disasters and events beyond our control led to the failure of accomplishing our goal.”

The report attributes the project’s failure to a range of causes including hypoxia, the 2019 Bonnet Carré openings, tropical storms and commercial harvesting that the governing board of Marine Resources allowed on the newly restored reefs.

By January 2021, the Marine Resources Department publicly conceded the “uncertainty” of investing in western Sound oyster restoration because of more frequent Bonnet Carré openings. Marine Resources managers said they had started shifting efforts to the east, where water bottoms suitable for oysters are far more limited, by 2016.

The Environmental Quality agency has had a reef project in the central Sound since 2016. Since it started, the project has struggled with materials, cost and timing. Final results are still pending, but monitoring shows more reef loss than gain in the areas planted. Most of the sites tested so far show live oysters, although they were present in significant numbers on only half the subplots planted with limestone. Marine Resources says the project was intended to test reef material, not grow large amounts of oysters.

Environmental Quality spent almost $2.5 million deploying the limestone. The overall project, which includes mapping, monitoring and other components, is expected to cost $11.7 million.

“The point of this project was to see if this technique would be helpful across the program,” said Valerie Alley, program management division chief of Environmental Quality’s Office of Restoration. “So anything it tells us is good. It’s either we do it this way or we need to find another way, right?”

Another BP-funded oyster project in the eastern Sound was awarded $4.1 million in 2019. Located off the shores of Pascagoula, a city known for building military ships, it will not proceed as originally planned.

Environmental Quality had planned to move oysters from a Pascagoula reef where water is polluted to an area where they could purge themselves and be safe for consumption.

But Environmental Quality Executive Director Chris Wells said that too few oysters were found on the reef for relocation. Instead, the agency hopes to use most of the funding to build up the reef, which would be good for the oysters and for the environment. “If we can replenish that oyster reef, or any oyster reefs over there, you get oysters in the water and they start filtering and that improves water quality,” Wells said.

Should Reefs Be Privatized?

Aaron Tillman used to love fishing for oysters off the shores of Pass Christian. The reefs are close enough to shore that he could catch his limit for the day and be home for dinner.

The 48-year-old is a third-generation fisherman; his nine brothers and stepbrothers were also fishermen, but he’s the only one left in the business.

It hasn’t been easy, and today, he’s running out of the Pass Christian harbor and fishing for oysters. Just not in Mississippi.

Instead, Tillman is fishing private leases that Crystal Seas Seafood maintains in Louisiana, where oyster grounds have been leased to individuals and businesses since the 1800s.

One reef is only 10 miles over the Mississippi-Louisiana state line, and was damaged by freshwater flooding in 2019, but the private lease grounds in Louisiana are producing oysters, while the public grounds he fished in Mississippi are closed because there are too few adult oysters to harvest.

After the die-off caused by the 2019 Bonnet Carré openings, Jenkins said Crystal Seas sprayed clean, dry oyster shell from its processing plant and turned over old oyster shell on its Louisiana reefs so oysters would grow again.

“The oysters in Louisiana are growing real good,” Tillman said after a recent three-day trip. “Plenty of oysters growing all over.”

There are a lot of differences between the two states: Louisiana has much more water and more harvestable reefs than Mississippi does, and the water flows in different ways, so the impacts of natural and manmade disasters are not the same in both states.

But even accounting for those differences, officials who work on oyster projects in both states said Louisiana’s reefs are healthier in part because of who manages them: Fishermen hold leases on about 400,000 acres of Louisiana water bottoms, while the state maintains 38,000 acres of reefs. The state concedes that the private lease grounds are in far better shape than the state-maintained grounds.

In Louisiana, 99% of the oyster harvest came from private leases in 2021, said Carolina Bourque, oyster program manager for the state Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. In Mississippi, by contrast, records show no harvest of significance on leased reefs since 2016; that year, the catch on privately leased reefs was less than 1% of the total.

The spillway openings did damage in Louisiana, Bourque said. But even though the freshwater damaged some private leases, she said “they were fast coming back.” She said this was possible because private fishermen were able to replace material on the reefs right away.

Mississippi has been slow to expand private leasing, one of many recommendations that were made in the June 2015 Governor’s Oyster Council report. The state Legislature in 2015 expanded lease terms from one to five years and is currently working on a bill to open more areas for private leasing. Marine Resources administrators say they work with private leaseholders in Mississippi, but only a few are active.

One of the upsides of private leasing is that companies are highly motivated to keep their acres in good shape.

“When it’s your money on the line,” Jenkins, the manager of Crystal Seas, said, “you learn fast.”

In Louisiana, Bourque said leaseholders were able to replant quickly after the 2019 Bonnet Carré openings, while states can wait several years for federal disaster funding and depend on Mother Nature to replenish reefs.

Jenkins thinks oysters can still be grown in the western Sound with the right management techniques.

“They’re growing them in Louisiana 3 miles away,” she said, “so there’s no big wall out there that doesn’t allow it to happen here.”

How Cigna Saves Millions by Having Its Doctors Reject Claims Without Reading Them

This article first appeared at ProPublica and The Capitol Forum. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

When a stubborn pain in Nick van Terheyden’s bones would not subside, his doctor had a hunch what was wrong.

Without enough vitamin D in the blood, the body will pull that vital nutrient from the bones. Left untreated, a vitamin D deficiency can lead to osteoporosis.

A blood test in the fall of 2021 confirmed the doctor’s diagnosis, and van Terheyden expected his company’s insurance plan, managed by Cigna, to cover the cost of the bloodwork. Instead, Cigna sent van Terheyden a letter explaining that it would not pay for the $350 test because it was not “medically necessary.”

The letter was signed by one of Cigna’s medical directors, a doctor employed by the company to review insurance claims.

Something about the denial letter did not sit well with van Terheyden, a 58-year-old Maryland resident. “This was a clinical decision being second-guessed by someone with no knowledge of me,” said van Terheyden, a physician himself and a specialist who had worked in emergency care in the United Kingdom.

The vague wording made van Terheyden suspect that Dr. Cheryl Dopke, the medical director who signed it, had not taken much care with his case.

Van Terheyden was right to be suspicious. His claim was just one of roughly 60,000 that Dopke denied in a single month last year, according to internal Cigna records reviewed by ProPublica and The Capitol Forum.

The rejection of van Terheyden’s claim was typical for Cigna, one of the country’s largest insurers. The company has built a system that allows its doctors to instantly reject a claim on medical grounds without opening the patient file, leaving people with unexpected bills, according to corporate documents and interviews with former Cigna officials. Over a period of two months last year, Cigna doctors denied over 300,000 requests for payments using this method, spending an average of 1.2 seconds on each case, the documents show. The company has reported it covers or administers health care plans for 18 million people.

Before health insurers reject claims for medical reasons, company doctors must review them, according to insurance laws and regulations in many states. Medical directors are expected to examine patient records, review coverage policies and use their expertise to decide whether to approve or deny claims, regulators said. This process helps avoid unfair denials.

But the Cigna review system that blocked van Terheyden’s claim bypasses those steps. Medical directors do not see any patient records or put their medical judgment to use, said former company employees familiar with the system. Instead, a computer does the work. A Cigna algorithm flags mismatches between diagnoses and what the company considers acceptable tests and procedures for those ailments. Company doctors then sign off on the denials in batches, according to interviews with former employees who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“We literally click and submit,” one former Cigna doctor said. “It takes all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

Not all claims are processed through this review system. For those that are, it is unclear how many are approved and how many are funneled to doctors for automatic denial.

Insurance experts questioned Cigna’s review system.

Patients expect insurers to treat them fairly and meaningfully review each claim, said Dave Jones, California’s former insurance commissioner. Under California regulations, insurers must consider patient claims using a “thorough, fair and objective investigation.”

“It’s hard to imagine that spending only seconds to review medical records complies with the California law,” said Jones. “At a minimum, I believe it warrants an investigation.”

Within Cigna, some executives questioned whether rendering such speedy denials satisfied the law, according to one former executive who spoke on condition of anonymity because he still works with insurers.

“We thought it might fall into a legal gray zone,” said the former Cigna official, who helped conceive the program. “We sent the idea to legal, and they sent it back saying it was OK.”

Cigna adopted its review system more than a decade ago, but insurance executives say similar systems have existed in various forms throughout the industry.

In a written response, Cigna said the reporting by ProPublica and The Capitol Forum was “biased and incomplete.”

Cigna said its review system was created to “accelerate payment of claims for certain routine screenings,” Cigna wrote. “This allows us to automatically approve claims when they are submitted with correct diagnosis codes.”

When asked if its review process, known as PXDX, lets Cigna doctors reject claims without examining them, the company said that description was “incorrect.” It repeatedly declined to answer further questions or provide additional details. (ProPublica employees’ health insurance is provided by Cigna.)

Former Cigna doctors confirmed that the review system was used to quickly reject claims. An internal corporate spreadsheet, viewed by the news organizations, lists names of Cigna’s medical directors and the number of cases each handled in a column headlined “PxDx.” The former doctors said the figures represent total denials. Cigna did not respond to detailed questions about the numbers.

Cigna’s explanation that its review system was designed to approve claims didn’t make sense to one former company executive. “They were paying all these claims before. Then they weren’t,” said Ron Howrigon, who now runs a company that helps private doctors in disputes with insurance companies. “You’re talking about a system built to deny claims.”

Cigna emphasized that its system does not prevent a patient from receiving care — it only decides when the insurer won’t pay. “Reviews occur after the service has been provided to the patient and does not result in any denials of care,” the statement said.

“Our company is committed to improving health outcomes, driving value for our clients and customers, and supporting our team of highly-skilled Medical Directors,” the company said.

PXDX

Cigna’s review system was developed more than a decade ago by a former pediatrician.

After leaving his practice, Dr. Alan Muney spent the next several decades advising insurers and private equity firms on how to wring savings out of health plans.

In 2010, Muney was managing health insurance for companies owned by Blackstone, the private equity firm, when Cigna tapped him to help spot savings in its operation, he said.

Insurers have wide authority to reject claims for care, but processing those denials can cost a few hundred dollars each, former executives said. Typically, claims are entered into the insurance system, screened by a nurse and reviewed by a medical director.

For lower-dollar claims, it was cheaper for Cigna to simply pay the bill, Muney said.

“They don’t want to spend money to review a whole bunch of stuff that costs more to review than it does to just pay for it,” Muney said.

Muney and his team had solved the problem once before. At UnitedHealthcare, where Muney was an executive, he said his group built a similar system to let its doctors quickly deny claims in bulk.

In response to questions, UnitedHealthcare said it uses technology that allows it to make “fast, efficient and streamlined coverage decisions based on members benefit plans and clinical criteria in compliance with state and federal laws.” The company did not directly address whether it uses a system similar to Cigna.

At Cigna, Muney and his team created a list of tests and procedures approved for use with certain illnesses. The system would automatically turn down payment for a treatment that didn’t match one of the conditions on the list. Denials were then sent to medical directors, who would reject these claims with no review of the patient file.

Cigna eventually designated the list “PXDX” — corporate shorthand for procedure-to-diagnosis. The list saved money in two ways. It allowed Cigna to begin turning down claims that it had once paid. And it made it cheaper to turn down claims, because the company’s doctors never had to open a file or conduct any in-depth review. They simply denied the claims in bulk with an electronic signature.

“The PXDX stuff is not reviewed by a doc or nurse or anything like that,” Muney said.

The review system was designed to prevent claims for care that Cigna considered unneeded or even harmful to the patient, Muney said. The policy simply allowed Cigna to cheaply identify claims that it had a right to deny.

Muney said that it would be an “administrative hassle” to require company doctors to manually review each claim rejection. And it would mean hiring many more medical directors.

“That adds administrative expense to medicine,” he said. “It’s not efficient.”

But two former Cigna doctors, who did not want to be identified by name for fear of breaking confidentiality agreements with Cigna, said the system was unfair to patients. They said the claims automatically routed for denial lacked such basic information as race and gender.

“It was very frustrating,” one doctor said.

Some state regulators questioned Cigna’s PXDX system.

In Maryland, where van Terheyden lives, state insurance officials said the PXDX system as described by a reporter raises “some red flags.”

The state’s law regulating group health plans purchased by employers requires that insurance company doctors be objective and flexible when they sit down to evaluate each case.

If Cigna medical directors are “truly rubber-stamping the output of the matching software without any additional review, it would be difficult for the medical director to comply with these requirements,” the Maryland Insurance Administration wrote in response to questions.

Medicare and Medicaid have a system that automatically prevents improper payment of claims that are wrongly coded. It does not reject payment on medical grounds.

Within the world of private insurance, Muney is certain that the PXDX formula has boosted the corporate bottom line. “It has undoubtedly saved billions of dollars,” he said.

Insurers benefit from the savings, but everyone stands to gain when health care costs are lowered and unneeded care is denied, he said.

Speedy Reviews

Cigna carefully tracks how many patient claims its medical directors handle each month. Twelve times a year, medical directors receive a scorecard in the form of a spreadsheet that shows just how fast they have cleared PXDX cases.

Dopke, the doctor who turned down van Terheyden, rejected 121,000 claims in the first two months of 2022, according to the scorecard.

Dr. Richard Capek, another Cigna medical director, handled more than 80,000 instant denials in the same time span, the spreadsheet showed.

Dr. Paul Rossi has been a medical director at Cigna for over 30 years. Early last year, the physician denied more than 63,000 PXDX claims in two months.

Rossi, Dopke and Capek did not respond to attempts to contact them.

Howrigon, the former Cigna executive, said that although he was not involved in developing PXDX, he can understand the economics behind it.

“Put yourself in the shoes of the insurer,” Howrigon said. “Why not just deny them all and see which ones come back on appeal? From a cost perspective, it makes sense.”

Cigna knows that many patients will pay such bills rather than deal with the hassle of appealing a rejection, according to Howrigon and other former employees of the company. The PXDX list is focused on tests and treatments that typically cost a few hundred dollars each, said former Cigna employees.

“Insurers are very good at knowing when they can deny a claim and patients will grumble but still write a check,” Howrigon said.

Muney and other former Cigna executives emphasized that the PXDX system does leave room for the patient and their doctor to appeal a medical director’s decision to deny a claim.

But Cigna does not expect many appeals. In one corporate document, Cigna estimated that only 5% of people would appeal a denial resulting from a PXDX review.

“A Negative Customer Experience”

In 2014, Cigna considered adding a new procedure to the PXDX list to be flagged for automatic denials.

Autonomic nervous system testing can help tell if an ailing patient is suffering from nerve damage caused by diabetes or a variety of autoimmune diseases. It’s not a very involved procedure — taking about an hour — and it costs a few hundred dollars per test.

The test is versatile and noninvasive, requiring no needles. The patient goes through a handful of checks of heart rate, sweat response, equilibrium and other basic body functions.

At the time, Cigna was paying for every claim for the nerve test without bothering to look at the patient file, according to a corporate presentation. Cigna officials were weighing the cost and benefits of adding the procedure to the list. “What is happening now?” the presentation asked. “Pay for all conditions without review.”

By adding the nerve test to the PXDX list, Cigna officials estimated, the insurer would turn down more than 17,800 claims a year that it had once covered. It would pay for the test for certain conditions, but deny payment for others.

These denials would “create a negative customer experience” and a “potential for increased out of pocket costs,” the company presentation acknowledged.

But they would save roughly $2.4 million a year in medical costs, the presentation said.

Cigna added the test to the list.

“It’s Not Good Medicine”

By the time van Terheyden received his first denial notice from Cigna early last year, he had some answers about his diagnosis. The blood test that Cigna had deemed “not medically necessary” had confirmed a vitamin D deficiency. His doctor had been right, and recommended supplements to boost van Terheyden’s vitamin level.

Still, van Terheyden kept pushing his appeal with Cigna in a process that grew more baffling. First, a different Cigna doctor reviewed the case and stood by the original denial. The blood test was unnecessary, Cigna insisted, because van Terheyden had never before been found to lack sufficient vitamin D.

“Records did not show you had a previously documented Vitamin D deficiency,” stated a denial letter issued by Cigna in April. How was van Terheyden supposed to document a vitamin D deficiency without a test? The letter was signed by a Cigna medical director named Barry Brenner.

Brenner did not respond to requests for comment.

Then, as allowed by his plan, van Terheyden took Cigna’s rejection to an external review by an independent reviewer.

In late June — seven months after the blood test — an outside doctor not working for Cigna reviewed van Terheyden’s medical record and determined the test was justified.

The blood test in question “confirms the diagnosis of Vit-D deficiency,” read the report from MCMC, a company that provides independent medical reviews. Cigna eventually paid van Terheyden’s bill. “This patient is at risk of bone fracture without proper supplementations,” MCMC’s reviewer wrote. “Testing was medically necessary and appropriate.”

Van Terheyden had known nothing about the vagaries of the PXDX denial system before he received the $350 bill. But he did sense that very few patients pushed as hard as he had done in his appeals.

As a physician, van Terheyden said, he’s dumbfounded by the company’s policies.

“It’s not good medicine. It’s not caring for patients. You end up asking yourself: Why would they do this if their ultimate goal is to care for the patient?” he said.

“Intellectually, I can understand it. As a physician, I can’t. To me, it feels wrong.”

Annual Sign Up Drive Around the Corner

This is just a reminder that our annual TPM membership sign up drive is coming up soon. If you’re already a member, it’s an opportunity for us to thank you once again for being part of our team and making everything we do possible. If you haven’t signed up, please take the opportunity to do so during our drive. It’s pretty cheap to join for a Prime membership, not much more than the cost of one snazzy cup of coffee per month. You get access to every article we publish along with fewer ads. You also support our work, our place in the media ecosystem and you help us do even more of it. So during our drive we’re going to be talking about what we do, how we consistently punch above our weight as an organization and have the freedom to cut through a lot of the cant, unjustified assumptions and misbegotten and outdated rules we can happily violate.

As part of this I’m going to be asking existing members what makes TPM a must-read for them, where does TPM fit into the political news ecosystem for you. So look forward to that. Thanks to existing members and if you’re considering joining please do so during our drive!

Texas Has Been Spending Federal COVID Money On A Big Border Display Of Force

The Texas lawmaker sponsoring a sweeping effort to give the state unprecedented new powers to enforce the border says that his proposal is about a few things only: fentanyl, the cartels, and saving money.

Continue reading “Texas Has Been Spending Federal COVID Money On A Big Border Display Of Force”All Reporters Agree: DeSantis is Toast!

NBC just moved this story: RON DESANTIS’ DONORS AND ALLIES QUESTION IF HE’S READY FOR 2024. I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that this is becoming an example of the kind of press groupthink we often, very rightly, view with disdain. But it’s still remarkable how quickly many of DeSantis’s biggest backers, or most significant potential backers, have decided he’s not ready for prime time. The piece is based on comments by, interviews with and reports about a range of GOP bigwigs. But it largely focuses on the GOP megadonors who increasingly dominate GOP campaigns as the GOP small-donor world has atrophied. They’re talking about taking a “pause,” pumping the “brakes.” It’s embarrassing and frankly humiliating for DeSantis, who has experienced several such dignity-draining moments of late. But this is all a product of the last two weeks. It’s a rapid shift in conventional wisdom that is driven in large part by groupthink. It’s like a run on the National Bank of DeSantis. The difference is that, in this case, it’s a rapid shift in the direction of a more realistic take on DeSantis’s prospects.

Continue reading “All Reporters Agree: DeSantis is Toast!”Through A Year Of Drama, The Manhattan DA Investigating Trump Has Vowed To ‘Execute And Prosecute’

Alvin Bragg has spent a long time now in the eye of the storm — or, rather, a series of storms.

Continue reading “Through A Year Of Drama, The Manhattan DA Investigating Trump Has Vowed To ‘Execute And Prosecute’”A Lot of People are Rooting for DeSantis to Fail

One thing to consider as we watch Ron DeSantis’s campaign get started is just who is for him. Or perhaps there’s a better way to put it: Is anyone for him? My point here isn’t aggregate support. Polls suggest he currently has the support of between a quarter and a third of GOP primary voters. That’s a lot. But here I mean support in a more visible sense — among party and political elites, in the media, among fellow elected officials.

Continue reading “A Lot of People are Rooting for DeSantis to Fail”