A reporter in Traverse City, Michigan was allegedly assaulted during an anti-mask rally, and now the sheriff’s office is seeking information on one of the two men potentially involved.

Calculating The Costs Of The Afghanistan War In Lives, Dollars And Years

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It first appeared at The Conversation.

The U.S. invaded Afghanistan in late 2001 to destroy al-Qaida, remove the Taliban from power and remake the nation. On Aug. 30, 2021, the U.S. completed a pullout of troops from Afghanistan, providing an uncertain punctuation mark to two decades of conflict.

For the past 11 years I have closely followed the post-9/11 conflicts for the Costs of War Project, an initiative that brings together more than 50 scholars, physicians and legal and human rights experts to provide an account of the human, economic, budgetary and political costs and consequences of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Of course, by themselves figures can never give a complete picture of what happened and what it means, but they can help put this war in perspective.

The 20 numbers highlighted below, some drawn from figures released on Sept. 1, 2021, by the Costs of War Project, help tell the story of the Afghanistan War.

From 2001 to 2021

On Sept. 18, 2001, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 420-1 and the Senate 98-0 to authorize the United States to go to war, not just in Afghanistan, but in an open-ended commitment against “those responsible for the recent attacks launched against the United States.” U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee of California cast the only vote opposed to the war.

In other words, the U.S. Congress took 7 days after the 9/11 attacks to deliberate on and authorize the war.

At 7,262 days from the first attack on Afghanistan to the final troop pullout, Afghanistan is said to be the U.S.‘s longest war. But it isn’t – the U.S. has not officially ended the Korean War. And U.S. operations in Vietnam, which began in the mid-1950s and included the declared war from 1965-1975, also rival Afghanistan in longevity.

U.S. President George W. Bush told members of Congress in a joint session on Sept. 20, 2001 that the war would be global, overt, covert and could last a very long time.

“Our war on terror begins with al-Qaida, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated. … Americans should not expect one battle, but a lengthy campaign, unlike any other we have ever seen,” he said.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Neta C. Crawford, Boston University

The U.S. started bombing Afghanistan a few weeks later. The Taliban surrendered in Kandahar on Dec. 9, 2001. The U.S. began to fight them again in earnest in March 2002. In April 2002, President Bush promised to help bring “true peace” to Afghanistan: “Peace will be achieved by helping Afghanistan develop its own stable government. Peace will be achieved by helping Afghanistan train and develop its own national army. And peace will be achieved through an education system for boys and girls which works.”

The global war on terror was not confined to operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The U.S. now has counterterrorism operations in 85 countries.

The human cost

Most Afghans alive today were not born when the U.S. war began. The median age in Afghanistan is just 18.4 years old. Including their country’s war with the Soviet Union from 1979 to 1989 and civil war in the 1990s, most Afghans have lived under nearly continuous war.

There are, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 980,000 U.S. Afghanistan war veterans. Of these men and women, 507,000 served in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

As of mid-August 2021, 20,722 members of the U.S. military had been wounded in action in Afghanistan, not including the 18 who were injured in the attack by ISIS-K outside the airport in Kabul on Aug. 26, 2021.

Of the veterans who were injured and lost a limb in the post-9/11 wars, many lost more than one. According to Dr. Paul Pasquina of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, of these veterans, “About 40% to 60% also sustained a brain injury. Because of some of the lessons learned and the innovations that have taken place on the battlefield … we were taking care of service members who in previous conflicts would have died.”

In fact, because of advances in trauma care, more than 90% of all soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq who were injured in the field survived. Many of the seriously injured survived wounds that in the past might have killed them.

In all, 2,455 U.S. service members were killed in the Afghanistan War. The figure includes 13 U.S. troops who were killed by ISIS-K in the Kabul airport attack on Aug. 26, 2021.

Afghanistan.

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

U.S. deaths in Operation Enduring Freedom also include 130 service members who died in other locations besides Afghanistan, including Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Philippines, Seychelles, Sudan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uzbekistan and Yemen.

The U.S. has paid US$100,000 in a “death gratuity” to the survivors of each of the service members killed in the Afghanistan war, totaling $245.5 million.

More than 46,000 civilians have been killed by all sides in the Afghanistan conflict. These are the direct deaths from bombs, bullets, blasts and fire. Thousands more have been injured, according to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan.

And while the number of Afghans leaving the country has increased in recent weeks, more than 2.2 million displaced Afghans were living in Iran and Pakistan at the end of 2020. The United Nations Refugee Agency reported in late August 2021 that since the start of that year, more than 558,000 people have been internally displaced, having fled their homes to escape violence.

According to the United Nations, in 2021 about a third of people remaining in Afghanistan are malnourished. About half of all children under 5 years old experience malnutrition.

The human toll also includes the hundreds of Pakistani civilians who were killed in more than 400 U.S. drone strikes since 2004. Those strikes happened as the U.S. sought to kill Taliban and al-Qaida leaders who fled and sheltered there in late 2001 after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. Pakistani civilians have also been killed in crossfire during fighting between militants and the Pakistani military.

The financial cost

In terms of the federal budget, Congress has allocated a bit over $1 trillion to the Department of Defense for the Afghanistan War. But all told, the Afghanistan War has cost much more than that. Including the Department of Defense spending, more than $2.3 trillion has been spent so far, including increases to the Pentagon’s base military budget due to the fighting, State Department spending to reconstruct and democratize Afghanistan and train its military, interest on borrowing to pay for the war, and spending for veterans in the Veteran Affairs system.

The total costs so far for all post-9/11 war veterans’ disability and medical care costs are about $465 billion through fiscal 2022. And this doesn’t include the future costs of all the post-9/11 veterans’ medical and disability care, which Harvard University scholar Linda Bilmes estimates will likely add about $2 trillion to the overall cost of care for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars between now and 2050.

The war in Afghanistan, like many other wars before it, began with optimistic assessments of a quick victory and the promise to rebuild at war’s end. Despite Bush’s warning of a lengthy campaign, few thought then that would mean decades. But 20 years later, the U.S is still counting the costs.![]()

Neta C. Crawford is a professor of Political Science and Department Chair at Boston University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article was updated on Sept. 1, 2021 to correct the total death gratuity paid to survivors of service members killed in the Afghanistan war to $245.5 million.

McCarthy And MTG Are Having Meltdowns Over Jan. 6 Records Requests For Some Reason

A lot of things happened. Here are some of the things.

Why U Mad Tho

House Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), who had a call with Trump during the Capitol insurrection, and far-right extremist Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) freaked out yesterday over the House Jan. 6 select committee’s request to telecommunications companies asking for records of certain people, including lawmakers.

- “It’s no longer Republicans versus Democrats. It’s more like Americans versus Communists,” Greene told Fox News host Tucker Carlson.

- Greene threatened revenge come 2022 if her party takes control of the House, saying that the telecommunication companies “better not play with these Democrats” because “Republicans are coming back into the majority in 2022 and we will take this very serious.”

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene on the Jan. 6 select committee requesting lawmakers' phone records from telecommunication companies: "It’s no longer Republicans versus Democrats. It’s more like Americans versus Communists." pic.twitter.com/gcnjESVmp4

— TPM Livewire (@TPMLiveWire) September 1, 2021

- McCarthy made a similar threat earlier in the day, vowing that “a Republican majority will not forget” if telecommunication companies comply with the committee’s request.

My statement on Democrats asking companies to violate federal law: pic.twitter.com/XELEVNbx65

— Kevin McCarthy (@GOPLeader) August 31, 2021

- Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH), who’s admitted to speaking to Trump “more than once” on Jan. 6, said last week that Democrats will be scrutinized by Republicans “if they cross this line.”

- By the way, the committee hasn’t publicly specified which lawmakers’ records they’re seeking.

- CNN has reported that Greene and Jordan are included in that group, but nothing has been confirmed. Additionally, McCarthy’s name wasn’t on the list, according to CNN.

Texas Republicans Score In Their War On Voting

Gov. Greg Abbott (R) is expected to sign the sweeping new restrictions on voting passed by GOP lawmakers after a ferocious battle with their Democratic colleagues, many of whom had earlier fled the state to prevent a vote on the legislation.

Supreme Court Silent As Six-Week Abortion Ban Takes Effect In Texas

With a 6-3 conservative majority, the Supreme Court stayed on the sidelines as Texas’ new six-week abortion ban went into effect last night.

- The high court did not weigh in on the emergency petition to block the law from taking effect.

- The new law is a serious encroachment on Roe v. Wade, banning abortions after six weeks and making no exceptions for rape or incest.

- It allows citizens to file civil lawsuits against doctors or anyone else who provides access to an abortion after that period–including people who merely drive someone to get the procedure.

- It puts a bounty on those who violate the law by ordering them pay the citizen who sued them $10,000.

We’re Ending The Forever War Whether The Blob Likes It Or Not

Biden is standing by his decision to pull out of Afghanistan by the August 31 deadline even as war hawks wring their hands:

Biden: I was not going to extend this forever war and I was not extending a forever exit pic.twitter.com/hXm6l20N8W

— Acyn (@Acyn) August 31, 2021

The President declared that the withdrawal was bigger than Afghanistan; it marks a “new era” of American foreign policy.

President Biden says decision to exit Afghanistan is about "ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries"https://t.co/sgXLAj9CPu pic.twitter.com/gLCSIptjl7

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) August 31, 2021

RonJohn Gets RealJohn

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) (privately) admitted that Trump’s lies about the 2020 election being “rigged,” a narrative Johnson himself has been peddling enthusiastically in front of the cameras, are bullshit:

EXCLUSIVE: Sen Ron Johnson blames Trump for losing Wisconsin in 2020 and tells me “there’s nothing obviously skewed about the results.” pic.twitter.com/OeRkVkkVAN

— Lauren Windsor (@lawindsor) August 31, 2021

Doctors are begging him to do the same about the ivermectin “miracle cure” for COVID-19.

Paul Ryan Gets Brave

The GOP ex-House speaker said the 2020 election was “not rigged” and that Trump “lost the election.”

The Musings Of A Facebook Cowboy

Rep. Clay Higgins (R-LA), whose state was pummeled by Hurricane Ida this week, had this to say yesterday as fellow brain geniuses Reps. Louie Gohmert (R-TX) and Lauren Boebert (R-CO) nodded behind him:

When asked about hurricane damage in his home state, Rep. Clay Higgins (R-LA) says, "Let me tell ya what would be a good start for the people of Louisiana: $85 billion worth of military equipment that was left behind in Afghanistan!" pic.twitter.com/LVMrTE0PvP

— The Recount (@therecount) August 31, 2021

It’s not true that the Taliban got ahold of $85 billion worth of U.S. military equipment that Louisianans could’ve used to bomb the hurricane or whatever.

Do you like Morning Memo? Let us know!

McCarthy Issues Trumpy Gripe Over Jan. 6 Panel’s Request To Social Media, Telecom Companies

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) on Tuesday predictably took a Trumpian approach to complaining about the Jan. 6 committee’s requests to 35 social media, email, and telecommunications firms to preserve records that it believes are relevant to its probe into the deadly Capitol insurrection. Continue reading “McCarthy Issues Trumpy Gripe Over Jan. 6 Panel’s Request To Social Media, Telecom Companies”

Hurricane Ida Turned Into A Monster Thanks To A Giant Warm Patch In The Gulf of Mexico

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It first appeared at The Conversation.

As Hurricane Ida headed into the Gulf of Mexico, a team of scientists was closely watching a giant, slowly swirling pool of warm water directly ahead in its path.

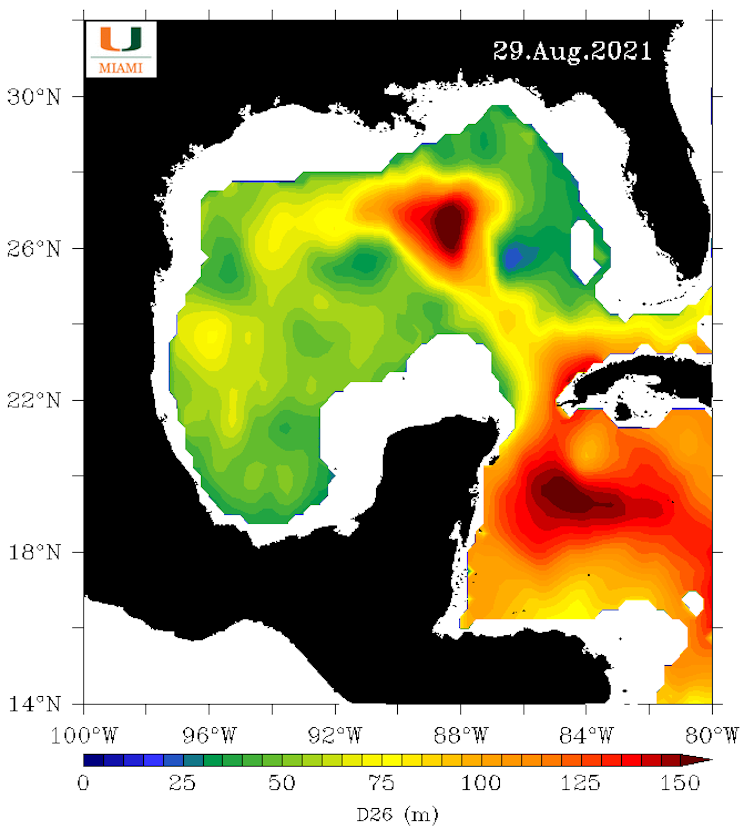

That warm pool, an eddy, was a warning sign. It was around 125 miles (200 kilometers) across. And it was about to give Ida the power boost that in the span of less than 24 hours would turn it from a weak hurricane into the dangerous Category 4 storm that slammed into Louisiana just outside New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2021.

Nick Shay, an oceanographer at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, was one of those scientists. He explains how these eddies, part of what’s known as the Loop Current, help storms rapidly intensify into monster hurricanes.

How do these eddies form?

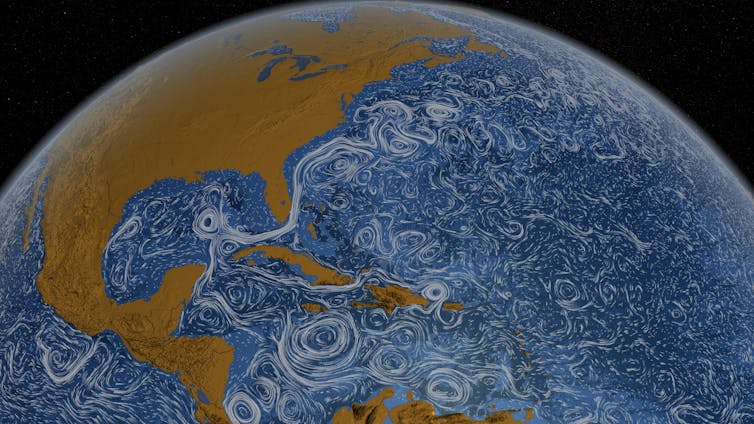

The Loop Current is a key component of a large gyre, a circular current, rotating clockwise in the North Atlantic Ocean. Its strength is related to the flow of warm water from the tropics and Caribbean Sea into the Gulf of Mexico and out again through the Florida Straits, between Florida and Cuba. From there, it forms the core of the Gulf Stream, which flows northward along the Eastern Seaboard.

In the Gulf, this current can start to shed large warm eddies when it gets north of about the latitude of Fort Myers, Florida. At any given time, there can be as many as three warm eddies in the Gulf. The problem comes when these eddies form during hurricane season. That can spell disaster for coastal communities around the Gulf.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Subtropical water has a different temperature and salinity than Gulf common water, so its eddies are easy to identify. They have warm water at the surface and temperatures of 78 degrees Fahrenheit (26 C) or more in water layers extending about 400 or 500 feet deep (about 120 to 150 meters). Since the strong salinity difference inhibits mixing and cooling of these layers, the warm eddies retain a considerable amount of heat.

When heat at the ocean surface is over about 78 F (26 C), hurricanes can form and intensify. The eddy that Ida passed over had surface temperatures over 86 F (30 C).

How did you know this eddy was going to be a problem?

We monitor ocean heat content from space each day and keep an eye on the ocean dynamics, especially during the summer months. Keep in mind that warm eddies in the wintertime can also energize atmospheric frontal systems, such as the “storm of the century” that caused snowstorms across the Deep South in 1993.

To gauge the risk this heat pool posed for Hurricane Ida, we flew aircraft over the eddy and dropped measuring devices, including what are known as expendables. An expendable parachutes down to the surface and releases a probe that descends about 1,300 to 5,000 feet (400 to 1,500 meters) below the surface. It then send back data about the temperature and salinity.

This eddy had heat down to about 480 feet (around 150 meters) below the surface. Even if the storm’s wind caused some mixing with cooler water at the surface, that deeper water wasn’t going to mix all the way down. The eddy was going to stay warm and continue to provide heat and moisture.

That meant Ida was about to get an enormous supply of fuel.

University of Miami, CC BY-ND

When warm water extends deep like that, we start to see the atmospheric pressure drop. The moisture transfers, also referred to as latent heat, from the ocean to atmosphere are sustained over the warm eddies since the eddies are not significantly cooling. As this release of latent heat continues, the central pressures continue to decrease. Eventually the surface winds will feel the larger horizontal pressure changes across the storm and begin to speed up.

That’s what we saw the day before Hurricane Ida made landfall. The storm was beginning to sense that really warm water in the eddy. As the pressure keeps going down, storms get stronger and more well defined.

When I went to bed at midnight that night, the wind speeds were about 105 miles per hour. When I woke up a few hours later and checked the National Hurricane Center’s update, it was 145 miles per hour, and Ida had become a major hurricane.

Is rapid intensification a new development?

We’ve known about this effect on hurricanes for years, but it’s taken quite a while for meteorologists to pay more attention to the upper ocean heat content and its impact on rapid intensification.

In 1995, Hurricane Opal was a minimal tropical storm meandering in the Gulf. Unknown to forecasters at the time, a big warm eddy was in the center of the Gulf, moving about as fast as Miami traffic in rush hour, with warm water down to about 150 meters. All the meteorologists saw in the satellite data was the surface temperature, so when Opal rapidly intensified on its way to eventually hitting the Florida Panhandle, it caught a lot of people by surprise.

Today, meteorologists keep a closer eye on where the pools of heat are. Not every storm has all the right conditions. Too much wind shear can tear apart a storm, but when the atmospheric conditions and ocean temperatures are extremely favorable, you can get this big change.

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, both in 2005, had pretty much the same signature as Ida. They went over a warm eddy that was just getting ready to be shed form the Loop Current.

Hurricane Michael in 2018 didn’t go over an eddy, but it went over the eddy’s filament – like a tail – as it was separating from the Loop Current. Each of these storms intensified quickly before hitting land.

Of course, these warm eddies are most common right during hurricane season. You’ll occasionally see this happen along the Atlantic Coast, too, but the Gulf of Mexico and the Northwest Caribbean are more contained, so when a storm intensifies there, someone is going to get hit. When it intensifies close to the coast, like Ida did, it can be disastrous for coastal inhabitants.

AP Photo/David J. Phillip

What does climate change have to do with it?

We know global warming is occurring, and we know that surface temperatures are warming in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere. When it comes to rapid intensification, however, my view is that a lot of these thermodynamics are local. How great a role global warming plays remains unclear.

This is an area of fertile research. We have been monitoring the Gulf’s ocean heat content for more than two decades. By comparing the temperature measurements we took during Ida and other hurricanes with satellite and other atmospheric data, scientists can better understand the role the oceans play in the rapid intensification of storms.

Once we have these profiles, scientists can fine-tune the computer model simulations used in forecasts to provide more detailed and accurate warnings in the futures.

![]()

Nick Shay is a professor of Oceanography at the University of Miami.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Where Things Stand: Native Tribes Have Been Bucking Anti-Mask Rules For A While

We’ve watched and covered public school districts in red states around the U.S. defying Republican governors’ orders against universal masking in schools for the past several weeks. But as sovereign nations, many Native American tribes around the country have been taking school-related COVID mitigation measures into their own hands for some time.

Continue reading “Where Things Stand: Native Tribes Have Been Bucking Anti-Mask Rules For A While”

Arrest Warrant Out For Angry White Dude Who Confronted Black Reporter During Ida Live-Shot

The white man who angrily confronted MSNBC correspondent Shaquille Brewster, a Black man, during live coverage of Hurricane Ida in Mississippi on Monday is wanted for arrest. Continue reading “Arrest Warrant Out For Angry White Dude Who Confronted Black Reporter During Ida Live-Shot”

Even With The Eviction Moratorium, Landlords Continued To Find Ways To Kick Renters Out

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It first appeared at The Conversation.

Millions of renters in the U.S. lost a key protection keeping them in their homes on Aug. 26, 2021, with a Supreme Court ruling ending a national moratorium on eviction.

The federal stay on evictions was put in place during the coronavirus pandemic to protect renters falling behind on monthly payments and therefore in danger of needing to stay at homeless shelters or with friends or relatives. This pandemic response was designed to keep tenants in their housing, prevent overcrowding in shelters and homes, and reduce the spread of COVID-19.

In early August, 7.9 million renter households reported being in arrears, with 3.5 million saying they were at risk of eviction within two months. The large number of tenants with rental debt and susceptible to displacement underscores the importance of protecting vulnerable renters during the pandemic.

As academic experts on homelessness and low-income housing at the University of Washington, we studied the housing experiences of low-income renters during the coronavirus pandemic. Our research found that even when a ban on evictions was in place, landlords still had ways to force, or at least encourage, renters to leave. Indeed, these so-called “informal evictions” – in which landlords harass tenants out of their homes – may even have increased as a result of the stay on evictions.

Different levels of protection

The federal eviction moratorium imposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in September 2020 – along with similar actions by 43 states and dozens of cities and counties – undoubtedly saved many families from being evicted. Analysis of court records has found these moratoriums prevented millions of eviction filings during the pandemic.

Each moratorium gave tenants different levels of protection. Some prevented landlords from filing eviction lawsuits in housing court, while others suspended only the final stage of eviction: the removal of tenants and their possessions by law enforcement.

John Moore/Getty Images

Forced out of homes

We studied the experiences of low-income renters between October 2020 and February 2021 in the state of Washington, considered to have one of the strongest eviction moratoriums in the country. Put in place on March 18, 2020, it prohibited landlords from filing, or threatening to file, evictions for unpaid rent – and banned rent increases and late fees.

Despite these protections, we found that some low-income renters were still being forced out of their homes, outside the formal legal process.

Landlords use a variety of tactics that put pressure on tenants to leave, such as harassing tenants through verbal abuse or making repeated requests to inspect or enter the rental unit, often without proper notice. Other landlords refuse to make necessary repairs or, conversely, initiate noncrucial construction work on the unit, disrupting things while the tenant is living there.

Such practices can put low-income tenants in an unenviable position: Either they leave their home or they continue to face nuisances and harassment from their landlord. Those who opt to remain may find themselves facing even more severe pressure.

Stephen Zenner/Getty Images

Illicit eviction tactics

The moratorium on evictions offered legal cover to tenants who refused their landlord’s order to leave. Tenants could contact the Washington State Attorney General’s Office for assistance in preventing an unlawful eviction. However, there are no substantive consequences for landlords who tell tenants to vacate their rental units – prosecutions are very rare.

Tactics such as changing front door locks to prevent tenant access and removing tenants’ possessions are illegal, but many renters don’t have the knowledge or resources to fight violations in a housing court and end up deciding to leave, even though they have the legal right to stay.

We spoke with an older couple who had rented from the same landlord for more than a decade. During the early months of the pandemic, they could manage to make only partial, but consistent, rent payments. In June 2020 – two weeks after asking for an extension on the next month’s rent – they came home to find that their landlord had changed the locks on their front door without informing them. He then refused to allow the couple to retrieve their possessions, leaving them to sleep in their car until they found a new place to live.

A low-income single mother with two children told us her landlord refused to fix a leaking roof that caused a severe problem with black mold. She believed the refusal was a result of her having missed multiple months of rent.

Another tenant we interviewed was visited by their landlord, sometimes with only 20 minutes’ notice, more than a dozen times in a few weeks shortly after they lost their job and could no longer pay full rent.

In all, with support from Violet Lavatai, executive director of the Tenants Union of Washington State, we spoke to 25 low-income tenants and analyzed 410 survey responses. All of our respondents had reached out to a tenants’ rights hotline at least once in the past few years.

[Over 110,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

In 2017, a national study estimated that 4.5% of all renters faced an informal eviction that year. For every one formal eviction there were up to 5.5 informal evictions.

Our research suggests that the stays on evictions during the pandemic might actually be driving an increase in informal evictions. Results of our survey indicate that informal evictions more than doubled during the pandemic compared with the prior year.

Vulnerable to coercive landlords

The Supreme Court’s decision to block the federal eviction moratorium leaves millions of renters in states that have no similar protection in place at risk of eviction, especially those who have not yet received rental assistance. Even for renters who are protected by state moratoriums, these protections are set to expire before the end of September 2021, including in Washington state.

Our research suggests that stays of evictions alone are not the solution to housing insecurity. Tenants who find themselves unable to pay rent are still vulnerable to the unlawful tactics of landlords determined to force them out.

The imposition of clear penalties for illicit evictions and greater support for low-income tenants could help many more low-income tenants stay in their homes.![]()

Matthew Fowle is a Ph.D. candidate in Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington.

Rachel Fyall is an associate professor of Public Policy & Governance at the University of Washington.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Feds Charge FL Developer In Alleged Gaetz Extortion Plot As Sex Probe Grinds On

As the federal investigation into Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) reportedly continues, there’s been a related charge in Pensacola, Florida: a man who allegedly tried to turn the Gaetz investigation into a personal payday.

Continue reading “Feds Charge FL Developer In Alleged Gaetz Extortion Plot As Sex Probe Grinds On”

Doctors Beg RonJohn To Stop ‘Horsing Around’ With Ivermectin Propaganda

Wisconsin physicians urged Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) during a virtual meeting on Monday to stop promoting ivermectin — the dewormer typically used on horses — as a treatment for COVID-19. It is not. Continue reading “Doctors Beg RonJohn To Stop ‘Horsing Around’ With Ivermectin Propaganda”