Some of the most radical legal theories which animated Donald Trump’s 2020 coup attempt filtered in from a once-obscure Wisconsin attorney.

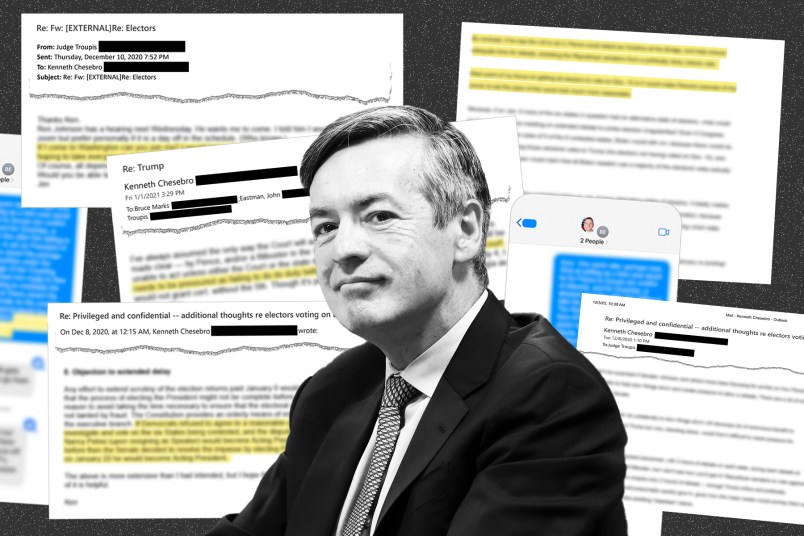

Ken Chesebro, an appellate lawyer and former acolyte of Harvard Law professor Larry Tribe, wound up as an ideas man for the Trump campaign’s last, most desperate grasps at power in late 2020 and early 2021, a trove of documents obtained by TPM shows.

He was the architect of the fake electors plan and, emails, texts, and memos reveal, played a critical role in developing the idea that Mike Pence had the power to gum up Congress on Jan. 6. That, Chesebro claimed, would start a chain reaction that could somehow lead to Trump’s re-inauguration on Jan. 20.

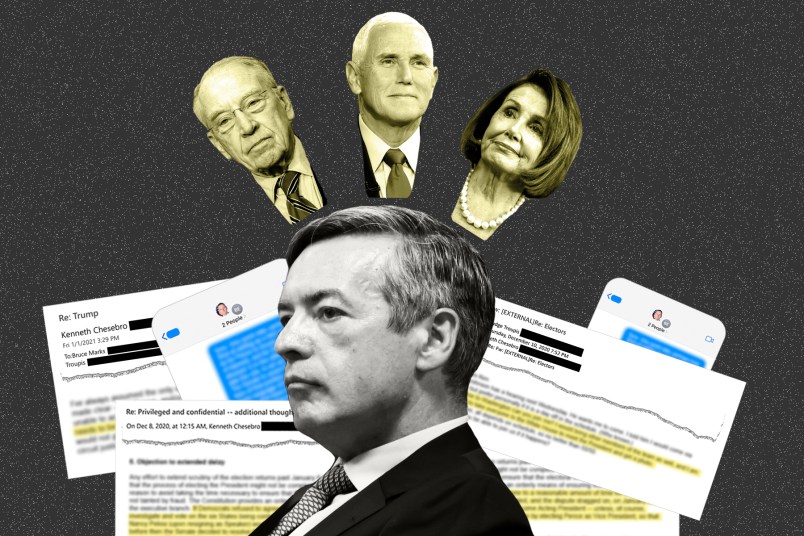

This article shows how some of the most radical ideas now associated with Jan. 6 filtered into the Trump campaign through three people who have been identified as unindicted co-conspirators listed in Jack Smith’s Jan. 6 indictment. They are Chesebro, law professor John Eastman, and a third figure: Boris Epshteyn, a longtime Trump surrogate, attorney, and political consultant who reportedly sent emails matching those sent by a figure described as co-conspirator 6 in the Smith indictment.

The trove of documents obtained by TPM reveals the division of labor between the three. Chesebro was an ideas man. Many of those ideas were divorced from the prior 150 years of practice. But Chesebro outlined a vision of Pence’s role — and of stalemate in Congress — which gave the Trump campaign what it was looking for, with academic laurels to boot: a shot at delaying the formalization of Biden’s win for as long as possible. Epshteyn emerges in this picture as a coordinator, tasking Chesebro with preparing legal memos and connecting him with Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani. Per the emails, Eastman largely begins to propose ideas after the fake elector scheme had been implemented, and complements Chesebro’s ideas while editing them and taking them to Trump’s inner circle.

TPM obtained the trove of documents after Michigan prosecutors received records from Ken Chesebro as part of their investigation into efforts to overturn the 2020 election. Chesebro supplied the documents, which include emails, texts, and legal memos, to prosecutors. It’s one tranche of evidence in a coup attempt that was much broader — it spanned months and involved hundreds of people — and was provided as Chesebro sought to avoid prosecution in Michigan.

The documents provide a look at the anatomy of the portion of the coup attempt which proceeded not through mobs at the Capitol or via angry tirades, but in staid legal briefs and hidebound argumentation, and which cast Vice President Mike Pence in a leading role.

Epshteyn, a prominent Trump surrogate since the 2016 campaign, has largely managed to maintain a lower profile than the other co-conspirators with respect to his involvement in the legal portion of the coup attempt. He wasn’t available for comment for this series. But the records show that he played a leading role in pulling together the legal theories that cast Jan. 6 as a critical date, asking Chesebro on Dec. 12 for “a memo on VP’s powers during Joint Session,” and, after receiving the now-infamous Eastman memo, asking about “steps that have to be taken BEFORE the 6th on this front?”

Chesebro also emerges from the emails and texts as a far more influential figure than previously understood. The records show that he provided substantial edits to the “Eastman memo,” which pushed the idea that Pence could unilaterally reject electoral votes on Jan. 6, and, in the three days before Jan. 6, peppered Epshteyn and Eastman with law review articles about the vice president’s ability to review and count electoral votes.

On a normal Jan. 6, according to the Electoral Count Act, the vice president opens the electoral votes submitted by the states. Before a 2022 reform went into effect, one senator and one representative objecting to a particular state’s results would lead to time-limited debate.

Chesebro volunteered the idea that Pence could throw a wrench in this process by declining to open Biden votes from swing states, instead using the fake electoral slates that Chesebro convened as a reason to not open any votes from those states. He brought this idea to an eager Trump campaign weeks ahead of the climactic series of meetings before Jan. 6 where Eastman and Trump sought to pressure Pence into stoking as much chaos as possible. The possibility that Pence might decline to open Biden votes at all was an option that Chesebro described as a “fairly boss move.”

The documents, combined with a 4.5 hour interview that Chesebro gave to Michigan prosecutors last year reviewed by TPM, also reveal for the first time that the group received an early “no” from Pence’s camp. Chesebro told prosecutors that he walked away from a call with a legal adviser to Pence one month before Jan. 6 with the distinct impression that Pence would not diverge from a single letter of the Electoral Count Act.

Despite that early demurral from Greg Jacob, Pence’s legal counsel, Chesebro spent the following weeks pushing for various ways that Pence could step beyond his authority to refuse to review electoral votes.

‘Horatius at the Bridge’

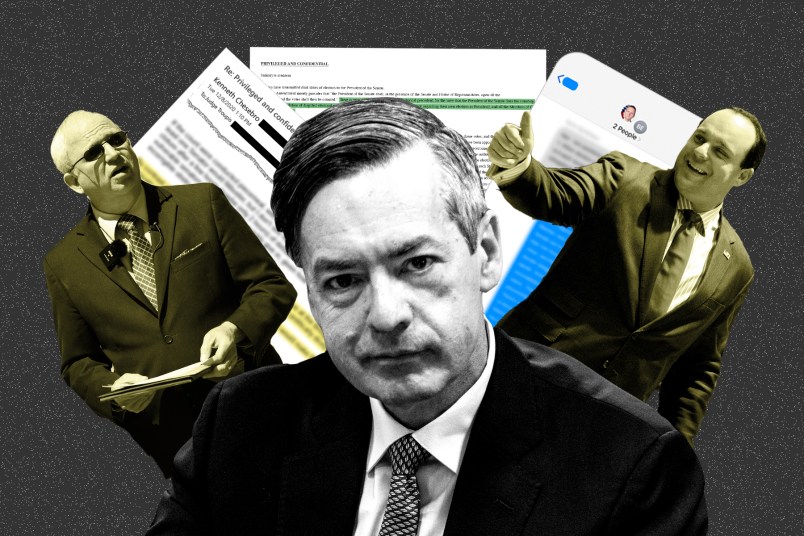

Chesebro had entered the Trump campaign’s post-election legal maneuvering in November via a lawsuit challenging the count in his home state of Wisconsin, an effort he worked on alongside an old friend of his, a former judge named Jim Troupis.

An early outline for “how leverage might be exerted in January” to force Congress to delay Biden’s certification in favor of examining claims of voter fraud came via a previously unreported Dec. 8 email to Troupis.

It contained a rough sketch of the pressure campaign that came to pass: the Electoral Count Act, which specified Pence’s role and time limits for debate, was unconstitutional and non-binding on Congress, Chesebro argued. It meant, he theorized, that if Republican senators and Pence cooperated, the Jan. 6 election certification vote could be extended for days, perhaps until Jan. 20, at which point the Senate could “resolve the impasse” by electing Pence vice president.

“By contrast, if he has the will to do it, Pence could stand as Horatius at the Bridge, and help ensure adequate time for debate,” Chesebro wrote in the Dec. 8 email, likening the vice president to an ancient Roman soldier who defended a bridge into Rome during a battle, becoming wounded but saving the city in so doing.

But what might induce Pence to bring Roman virtue into Trumpworld? Chesebro wrote that Pence could find justification for his bold move in fake slates of electors that the Trump campaign could convene from swing states. These electors would create the pretext of disputed victories, allowing Pence to refuse to open the Biden electors and thereby buy Trump, potentially, days — or weeks — of time.

The fake electors “would make Pence’s exercise of his power to set the pace of the count look much more reasonable,” Chesebro wrote.

A quick call with Pence’s lawyer

Chesebro did not wait long to see how his theory would fare in reality.

One day after Chesebro’s email to Troupis, Dec. 9, Epshteyn asked Troupis if he would be willing to prepare sample fake elector ballots for Wisconsin and, if he agreed, to do the same for six other states: Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico.

Troupis said yes, and forwarded Epshteyn’s email to Chesebro: could he or another Wisconsin attorney “do this for the other states?”

“Oh, absolutely!!!” Chesebro replied.

Chesebro, believing, as he put it in a Dec. 9 email to Troupis, that Pence was President of the Senate in 2016, arranged a call with Greg Jacob, Pence’s legal adviser.

Three years later, Chesebro recounted the conversation to Michigan prosecutors during a proffer interview.

“My immediate reaction was, well, I need to see the electoral votes that were cast in 2016. Thinking, well, the President of the Senate — that’s Pence! I’ll reach out to his staff and they’ll have copies,” Chesebro recalled in December 2023. “So I reached out, and eventually Greg Jacob, who’s the key lawyer for Pence, who ended up being in the meetings with Eastman, he and I had a nice discussion, and he explained that actually, the President of the Senate in 2016 was Biden, and they were in his papers, so we don’t have them, and it turned out they were online in the archive.”

Chesebro added that, after that flub, he “gently suggested” that Pence might decline to open the envelopes. Or, Chesebro recalled, that Pence might “skip the states in dispute,” and then “lump” them together at the end of the count to “create a critical mass of states that need to be considered separately, even though that would violate” the Electoral Count Act.

“I detected no enthusiasm,” Chesebro told prosecutors of Jacob’s response.

By that time, emails show, others on the original Wisconsin team had found the certificates Chesebro was searching for on the National Archives website. Three years later in an interview with Michigan prosecutors, Chesebro made his view of Pence clear: “Pence wouldn’t do anything anyway, because his lawyer wouldn’t even take a state out of order.”

Enter Boris

The next day, on Dec. 10, Troupis sent an email directing Chesebro to work with two Trump campaign attorneys: Justin Clark, a deputy campaign manager and attorney, and Boris Epshteyn, an attorney for the President.

Throughout, Epshteyn took on a coordinating role for Chesebro. He introduced Chesebro to Rudy Giuliani, and helped facilitate the fake electors effort. Emails and texts from the days before Dec. 14 — the day the fake electors convened — show Epshteyn coordinating with Chesebro and a coterie of other Trumpworld figures including Mike Roman.

The former mayor and Chesebro spoke on the phone on Dec. 10, the emails indicate.

Epshteyn also began to ask Chesebro to prepare legal arguments about Pence’s role.

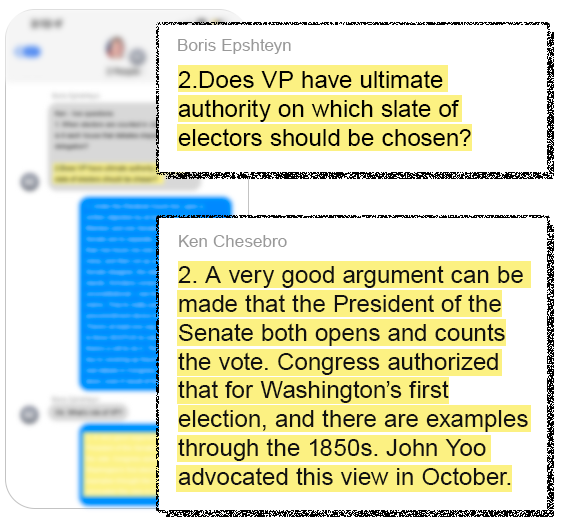

In a Dec. 12 text exchange between Epshteyn, Chesebro, and Trump operative Mike Roman, Epshteyn asked Chesebro whether Pence had the “ultimate authority on which slate of electors should be chosen.”

Chesebro, forever lawyerly, cited the election of George Washington, “numerous examples from the 1850s,” and an October 2020 column from John Yoo to give a qualified answer: yes.

Hours later, Epshteyn told Chesebro that he had briefed Giuliani. He then said “a memo on VP’s powers during Joint Session would be vital to have,” reminding him in a separate thread about the memo and peppering Chesebro with questions once it came through.

In his exchange with Epshteyn and Roman, Chesebro also mentioned that days before, on Dec. 9, he held a phone call with Jacob, Pence’s counsel. Chesebro was sparse on details in the texts to Epshteyn and Roman.

Three years later, Chesebro would tell prosecutors that he tailored his legal advice based on what Jacob told him: that Pence was not likely to do anything that Chesebro was proposing.

Editing Eastman

It’s not clear whether Chesebro’s Dec. 12 Pence memo, ordered by Epshteyn, went anywhere. The idea that Pence should do anything other than count the votes does not surface again in the documents shared with prosecutors until Dec. 23, when law professor John Eastman begins to work on the idea with Chesebro in his now-infamous Eastman memo.

Drafts in the trove show that Chesebro added chunks of text to the document highlighting Pence’s role, including a line citing “very solid legal authority” for the idea that Pence could both count and resolve “disputed electoral votes,” while “all the Members of Congress can do is watch.”

“Do we need to add any steps that have to be taken BEFORE the 6th on this front?” Epshteyn asked in a Dec. 23 response.

Chesebro, in a lengthy email 13 minutes later, replied that the Senate could hold hearings ahead of Jan. 6 on election fraud and the invalidity of the Electoral Count Act, but Eastman shot that idea down, writing: “Better for them just to act boldly and be challenged.”

Three years later, Chesebro would tell Michigan prosecutors that he knew at least some of their work made it to Trump’s inner circle via Epshteyn, who he described as “funneling” it out to GOP senators.

Chesebro spoke dismissively of Eastman in the interview with prosecutors, calling some of his legal ideas “ridiculous” and complaining that he had to send Eastman “basic law review articles on the Electoral Count Act and the 12th Amendment that he apparently had never looked at,” and that he was trying to “educate” Eastman about “stuff he was talking to the Vice President about.”

As Jan. 6 approached, Chesebro showered Eastman and Epshteyn with law review articles, including one where, Chesebro wrote, the author “sketched how Republicans in a setting like the one we now have could plausibly rely on the view that the President of the Senate counts the votes, to totally gum up the count.”

He also forwarded Eastman the Dec. 13 memo on Pence’s powers which Epshteyn had told him to write, and sent both Eastman and Epshteyn a Twitter thread featuring law professor Jed Shugerman, which, he said, “features a good summary of the other side. Jed is a rare honest liberal scholar.”

It’s not clear from the emails why Chesebro was sending these, though he told prosecutors in the interview three years later that Eastman had asked him to do so. Eastman met with Pence and Greg Jacob on Jan. 5, where he failed to persuade them to adopt the plan.

Nearly all of the law review articles were focused on the critical question: does the vice president count? For them, it was abstract. For the rest of the world, it was very real.

So, in reality, Mike Pence has Chesebro to thank for sending a mob after him that nearly lynched him on January 6.

I’ve never been clear on why New Mexico was included in the fake electors scheme. Biden won the state by nearly 11%.

Did the r’s think that the cowboys for trump would just lasso and brand the majority in New Mexico? That one’s a head scratcher.

Great job with this series, Josh.

To me, all the proof required to negate Trump’s whole legal argument is that they only sought to prove fraud in states that would have made a difference to him politically.

Fraud in Missouri? Don’t care. Hmmm.

Fraud that would necessitate Republicans who won having to be recounted? Don’t care.

This whole things is naked. He’s clothing himself in bullshit fast enough to seem like he’s wearing anything at all.

Corporate media is a mindless monster.

Or a mindful one.

Trump would have found a way. They were the justification end of an argument that he said he already won.

Probably a lot more gambits out there. I mean, Roger Stone at the same time is in the same hotel room as the coordinated attack teams from the Oath Keepers sent round lighting fires.

For the record, this:

. . . is the part of the Constitution where monkeys fly out of trump’s butt. There’s nothing whatsoever that gives the Senate any such authority. So the core of Chesebro’s entire scheme is just fucking up Congress’s shit so they can do a coup. I look forward to his forthcoming federal indictment and prison sentence.