Donald Trump’s attorneys in 2020 thought that they had one advantage which nobody — not the Democrats, not lower-court judges, not Congress — could outmatch: the Supreme Court.

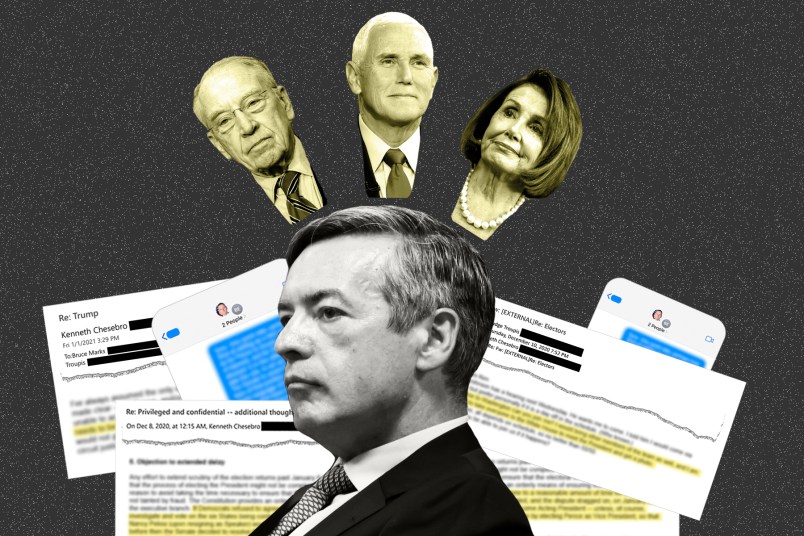

At their most feverish, attorneys for Trump believed that the Supreme Court could eventually be bullied into declaring Joe Biden the loser of the 2020 election and Trump the winner. They deployed a series of strategies, detailed in a trove of documents given to Michigan prosecutors by attorney Ken Chesebro, aimed at stoking a chaotic stalemate in Congress, thereby forcing the Court to act.

The same set of real-time emails and texts between Trump campaign officials and attorneys also shows how the group sought to influence individual justices as they filed lawsuits seeking to overturn Biden’s victory in several swing states. In the trove, attorneys game out which justices would view their claims most favorably, and speculate over how certain claims or lawsuits could create pressure to build a majority on the court.

At times, the Trump attorneys recognized that their play for the Supreme Court was a Hail Mary. It’s from that desperation, the documents suggest, that the push for chaos and delay emerged — a nearly hopeless quest to leave the Supreme Court as the only actor left standing, with Congress buckling under procedural radicalism.

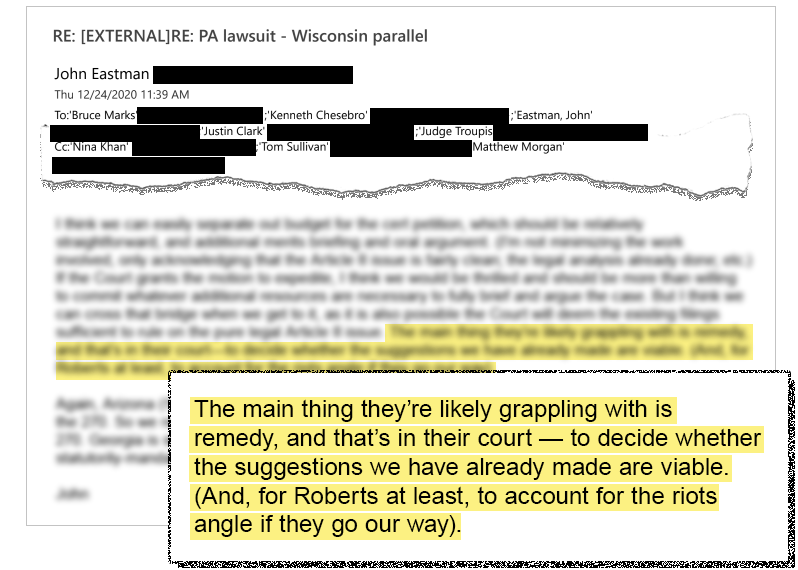

But at other points, the lawyers seemed deadly serious in their speculation. John Eastman, the law professor, wrote in one email that he believed the Supreme Court would probably agree to invalidate Pennsylvania Supreme Court decisions about the election, but that the justices were “likely grappling with” the question of what “remedy” to provide. Chief Justice John Roberts would want “to account for the riots angle if they go our way,” Eastman imagined.

This story largely plays out in the final weeks before Jan. 6, after the Trump campaign had finished convening slates of its own, fake presidential electors who were willing to cast ballots saying Trump, not Biden, had won their state. To the Trump campaign, that scheme, too, was a means to theorize the high court into wrenching states that it lost away from Biden. As Chesebro wrote in late November to several attorneys working on the campaign’s effort to invalidate the Wisconsin result, the point of convening fake electors would be “to benefit from an eventual U.S. Supreme Court ruling” voiding the election result, allowing the Trump electors to swoop in and replace the Biden electors from their state in the Electoral College.

But it wasn’t until mid December, after the fake electors were sworn in — and after the Supreme Court signaled that it would not help the Trump campaign, rejecting on Dec. 11 a lawsuit filed by the state of Texas — that conversations about how to exert pressure on the justices began to accelerate.

The New York Times reported on one of the emails obtained by TPM, in which Chesebro cited “wild chaos” as potentially forcing the Court to act, and another in which he stated that the question of whether to bring suits before the Court was “political.”

The trove of documents obtained by TPM paints a fuller picture. TPM obtained the documents after Michigan prosecutors with Attorney General Dana Nessel (D)’s office sent out a tranche of records provided by Chesebro as part of his cooperation with their investigation. Chesebro supplied the documents, which include emails, texts, and legal memos, to prosecutors. The records do not provide a comprehensive accounting of the Trump campaign’s entire effort to reverse the President’s loss; they reflect what Chesebro provided as he sought to avoid further prosecution.

The documents provide new details about and insights into the Trump campaign’s legal maneuvering before Jan. 6, a story we told in part I and part II of this series. They tell another story, too: how a group of attorneys for the Trump campaign, including Chesebro, sought to use lawsuits before the Court to advance their goal of reversing Trump’s loss, including by:

- Filing lawsuits before SCOTUS challenging the results in enough states to create the impression that more electoral votes were still in play than the margin by which Trump lost

- Forcing SCOTUS to step in by causing a stalemate in Congress on Jan. 6

- Bringing enough lawsuits to SCOTUS so as to pressure friendly justices to act more aggressively

The story picks up in the weeks after the election, when the Trump campaign filed lawsuits across the country, seeking to invalidate or overturn the results in several states. They lost in nearly every case that they brought, and saw dozens more lawsuits dismissed. As time ran out, they had to decide: Which cases should they continue to pursue through appeals to the Supreme Court?

At first, they focused on two lawsuits, one challenging the results in Pennsylvania and another in Wisconsin.

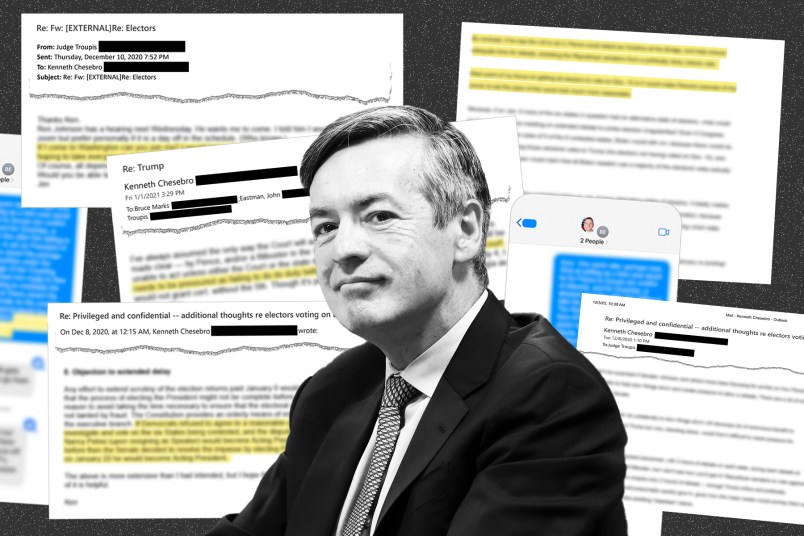

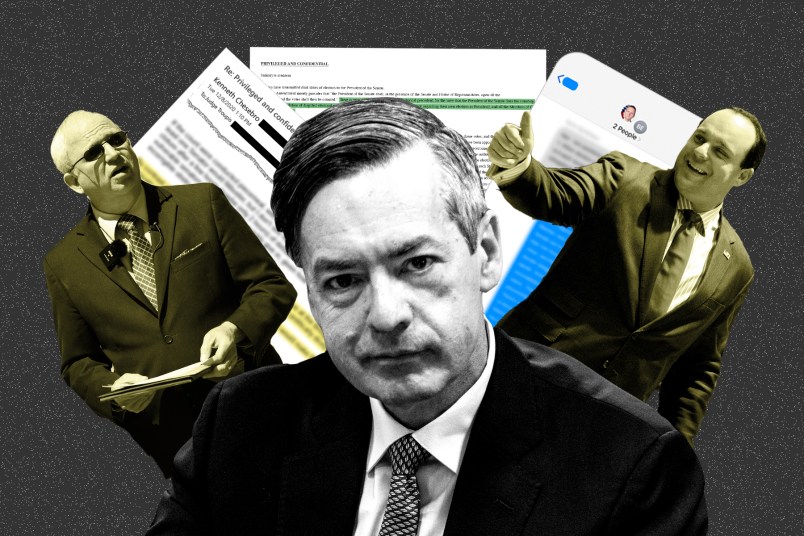

Chesebro had entered the Trump campaign’s legal world via his work on the Wisconsin case, which the state Supreme Court dismissed on Dec. 14. On Christmas Eve 2020, Chesebro found himself trying to persuade Trump campaign officials to give the green light on asking the Supreme Court to intervene in the matter.

Bruce Marks, a lawyer and former politician from Pennsylvania, was counsel, along with John Eastman, on a lawsuit the Trump campaign had filed asking the Supreme Court to hear a case that sought to reverse the result in Pennsylvania.

Marks had his own unique background: in the early 1990s, he lost a state Senate race, only to have a federal judge overturn the result and order him into office upon a finding of massive fraud in the election.

Marks’ story became a north star of Trump’s legal efforts in 2020, serving as an example of what the courts had the power to do, if they only had the will.

On the morning of Dec. 24, Trump campaign official Justin Clark emailed Marks, Chesebro, and other attorneys with an inquiry: If they brought their cases to the Supreme Court, what did they think the odds of winning were? And how much would pursuing the Wisconsin case before SCOTUS cost?

Marks replied that he believed bringing cases from additional states — including Wisconsin — before the Supreme Court would help his Pennsylvania case.

“While it is difficult to estimate success on Cert petitions, the success of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are intertwined,” Marks wrote to the group, copying Eastman on the exchange. “Wisconsin is an important step to getting to challenging 37 electoral votes.”

“Odds?” Eastman chimed in, responding to Clark’s request. He gave them odds: 10-20 percent that the Court would take the Pennsylvania case; “having Wisconsin in probably pushes that more towards the 20% side of the range or higher.”

“Odds of the Wisconsin case getting granted? ZERO if we don’t file,” Eastman added.

It was a carpe diem approach to seeking review from the Supreme Court, and one echoed by Chesebro, who wrote 10 minutes later that “you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take” and that he would defer to Eastman’s “personal insight” into which justices were the most distressed by the Trump campaign’s claims.

“A campaign that believes it really won the election would file a petition as long as it’s plausible and the resource constraints aren’t too great,” Chesebro wrote.

This intersected directly with the Trump campaign’s quest to find 270 electoral votes using non-electoral means. As Eastman wrote in a message a couple of hours later, a lawsuit to overturn the results in Arizona and Bruce Marks’ suit in Pennsylvania had already been filed before the Supreme Court — 31 electoral votes out of Biden’s lead of 36. Eastman wrote that Wisconsin, with 10 electoral votes, was “the most viable option to fill this gap.”

Earlier on in the Christmas Eve exchange, Wisconsin attorney and former judge Jim Troupis had warned the group: The path to success was “unclear” and “ill-defined.” The attorneys, he wrote, should be concerned about the “obligations” that come with asking the Supreme Court to hear a case. “I have made clear from the outset that I would strongly oppose any Petition where the goal is purely political,” Troupis wrote in an attachment cited by Chesebro.

“I don’t disagree with Judge Troupis’s comments here,” Chesebro replied, before going on to sketch out a theory over several emails throughout the day, proposing a plan to pressure the Supreme Court to overturn the election: the campaign could file enough Supreme Court cases to persuade the justices that they held the power to “change the electoral outcome.”

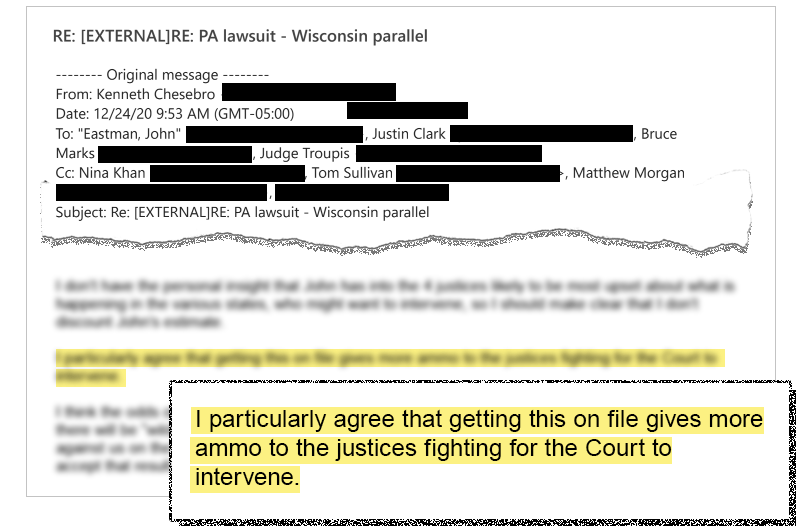

“Why intervene if it can make no difference in the end,” he wrote, apparently channelling what he hoped enough justices would come to believe. In a separate message that same day, Chesebro suggested to the group that Trump should file the lawsuit to sway internal Court politics, saying “getting this on file gives more ammo to the justices fighting for the Court to intervene,” he wrote.

Eastman wrote that he believed the campaign was on solid legal ground, and so the odds were based not on “the legal merits, but an assessment of the Justices’ spines,” before exhorting the group to help the justices who were “willing to do their duty” by filing the Wisconsin case.

After more back-and-forth, Eastman shared the theory that Chief Justice Roberts would likely be concerned, if the Court ruled in favor of Trump, about “the riots angle” — a premonition of what might come after handing Trump an election he lost.

Clark, the campaign official, wrote in to the sprawling thread two hours after Eastman’s “riots” email with some skepticism: he said that the campaign wouldn’t pay the attorneys “unless we get some wins,” and, worse for Chesebro and Eastman, that his impression was that the odds of success in Wisconsin were zero. He also echoed Chesebro’s theory that, if the election certification in Congress could be derailed, Jan. 6 could extend for days, writing “it also sounds like Jan 6 is a hard deadline for legal recourse unless congress doesn’t count the votes one way or another.”

The campaign eventually assented. On Dec. 29, Rudy Giuliani sent a certification authorizing the attorneys to ask the Supreme Court to hear the Wisconsin case.

The Trump attorneys were also reviewing the option of Georgia. At 16 electoral votes, it was a potentially lucrative prize to be stolen; but as Eastman had written in the Wisconsin thread, the campaign’s lawsuit in the state was “stuck in a quagmire with the state trial courts not even assigning a judge” to consider it.

The group decided to file a federal version of the Georgia lawsuit, seeing it as a way to get around what they regarded as an infuriating cold shoulder from the state judiciary. But a question continued to hang over their efforts, even as they continued into 2021: What was the point?

The attorneys had to keep themselves going — every day that the Supreme Court continued to ignore their filings was a reminder of just how unlikely their success was. Marks, the Pennsylvania attorney, wrote an email to attorneys involved in the Georgia case on New Years Eve asking if the federal judge could issue an injunction allowing the state legislature to appoint the Trump electors.

Chesebro replied within minutes that he saw an added benefit with Marks’ gambit: Georgia federal courts are in the 11th Circuit, which is overseen by Justice Clarence Thomas.

Again, Chesebro wrote, the point was to make a statement via the Court.

“Merely having this case pending in the Supreme Court, not ruled on, might be enough to delay consideration of Georgia, particularly if Pence has the legal ability and will to insert himself at least enough to win delay,” he wrote. “Realistically, our only chance to get a favorable judicial opinion by Jan. 6, which might hold up the Georgia count in Congress, is from Thomas — do you agree, Prof. Eastman?”

“I think I agree,” Eastman replied. All the Court needed to give was a “likely,” he wrote — some suggestion that a ruling which signaled some chance of winning down the line might be enough. After all, Eastman said, he was talking to Georgia lawmakers and Jan. 6 was one week away: all they needed was a small push to decertify Biden’s win in the state before the big day.

By that point, the emails suggest, even the most optimistic Trump attorneys were losing hope of a clear-cut win before the Supreme Court. In talking points for members of Congress emailed among Clark and the attorneys on New Year’s day, Eastman added rhetoric to that effect.

“The Supreme Court has made it clear that it has no intention of addressing this illegal and unconstitutional conduct,” he wrote. “So upholding the rule of law now falls to other constitutional actors who have constitutionally assigned roles.

At this point,” he concluded, “the best we can likely hope for is a strident dissent from Thomas or Alito that maps out the illegal conduct and the constitutional actors who can provide a remedy.”

Reading this finally makes it clear why the Electoral College will never, ever be repealed. Ever. The answer is simple. Money. In a simple popular vote, you add up the votes across the country and whoever got the most, wins. Period. End of conversation. All this bullshit with slates of electors and one layer of redundant pointlessness atop another is nothing more than a gold mine of legal fees. That’s right folks, the reason we will NEVER get rid of the Electoral College is because there is a massive legal infrastructure in every state that funnels gargantuan amounts of money to lawyers to litigate this bullshit. Millions of people vote even though their vote is irrelevant in their state, or risk disenfranchisement while the country faces the very real possibility of a fascist takeover, all so a handful of very well-connected lawyers can keep raking in mountains of cash arguing inane rhetorical points. American Exceptionalism my ass.

I can’ wait to read this. Kovensky’s series has been great so far!

Sixty-first time is the charm.

So they figured out the supremes would not be the immediate answer. They needed Pence to hew to the absurd scenarios of bullshit legalese in order to win the election. Thus follows Trump’s push via the insurrection to force Pence to delay or follow the illegal means to change the electoral vote.

You left a word out: “former.” Please do not fall into the trap of referring to him as the president. That’s sloppy and wrong.