Pete Seeger had been a really old guy for as long as I can remember. One of those people who simply don’t die. Like Nelson Mandela. Of course, our perceptions of age change with time. Even so, nearing 45 myself, Pete Seeger was legitimately old for most of my life. For me, because of my own interests and affinities, I cannot help seeing Seeger somewhat through the prism of Bob Dylan who he crossed paths with, dramatically, for just three or four years in the early 1960s. But of course he was much, much more than that and managed to touch an amazing number of different courses and rivulets of American history over almost a century of life.

Seeger was born into music. His father, Charles Seeger, was a composer and also a founder of the academic discipline of ethnomusicology. That put him in contact, as Seeger himself was, with the various recorders and musicologists who traversed the South and Appalachia in the early party of the 20th century making recordings of a whole world of white and African-American ‘folk’ music which formed the basis of a lot of what we call folk music, blues, country, and eventually Rock n’ Roll. People like the father and son team of John and Alan Lomax who trekked through the South making recordings for the Library of Congress. They ‘discovered’ Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter) in Louisiana’s Angola Prison Farm in 1933. A towering musician and force in American history whose echoes you can hear in all sorts of modern music who also had a bad habit getting into fights in which he sometimes killed people.

Some of this sense of ‘folk’ music was an illusion of the musicologists themselves, imagining they were finding an untouched ‘folk’ tradition which had actually been cut through for decades by a recording and music publishing tradition they were at least initially unaware of. Still, it brought a whole body of American music to a national and elite and even international audience.

Guthrie performing with Leadbelly. Chicago, 1940.

Out of prison and with various recording careers, Leadbelly was a fixture of the mid-40s New York City folk music scene with folks like Sonny Terry and Woody Guthrie and a still quite young Pete Seeger. It was actually a Leadbelly song “Goodnight, Irene” which was Seeger’s group, The Weavers’, massive hit in 1950. It peaked at #1 and was on the Billboard charts for 25 weeks. This was only a few years before Seeger’s career went into steep eclipse after being blacklisted in the 1950s.

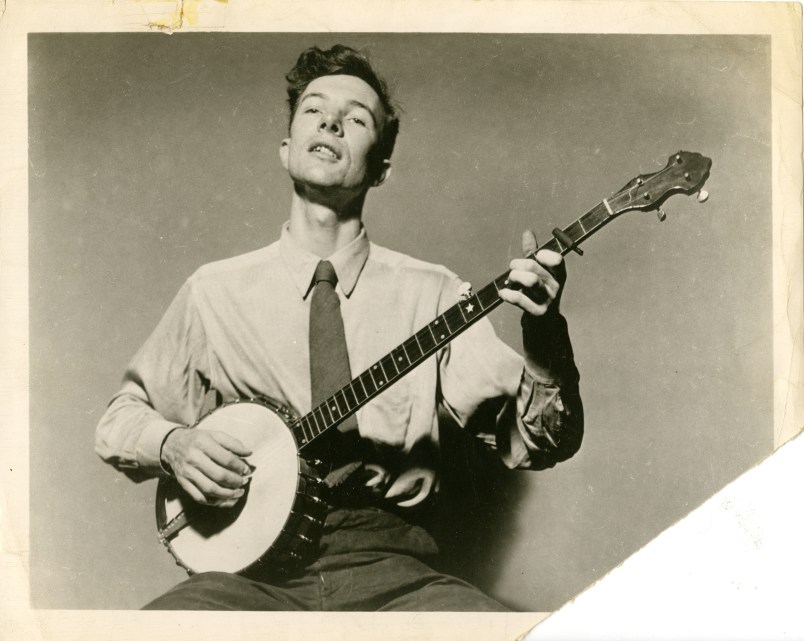

Pete Seeger performs for Eleanor Roosevelt and others at a racially integrated Valentine’s Day party in honor of the opening of a CIO hall. Washington, 1944. (Credit: Joseph Horne, Office of War Information)

But it’s that connection back to Woody Guthrie and that thread of folk music and radicalism stretching back to the 1930s and beyond that’s the thread that strikes the deepest chord for me. Folk music can mean a lot of things. But in the Guthrie-Seeger-Sonny Terry-Josh White sense it was as much a political ethos as a kind of music, and all mixed up with Labor radicalism, anti-racism, popular front politics, a deep stream of fellow-traveling. In the very nostalgia-drenched world of folk music there was a belief in something almost like an apostolic succession from Woody Guthrie on to Pete Seeger and then on to Bob Dylan. Or at least that’s what was supposed to happen. But the last part didn’t. And that’s what was behind all that crazy Folkie sense of betrayal about Dylan ‘going electric’ and ditching the whole Folk thing in 1965.

There is a real element (see A Mighty Wind) of the folk music tradition that can seem precious and vaguely ridiculous when looked at from the outside. Frankly, it can seem that way sometimes from the inside, too. A lot of the Dylan betrayal stuff brought that into the highest relief. Folk is a real and deep thing too, though, a deep river of America. Yet there was seldom much of any of that preciousness or heavy nostalgia in Seeger himself. And it was Seeger who turned out to be that thread and succession stretching out over 70 years.

The Weavers, 25th anniversary reunion, 1980. (AP/Richard Drew)

Guthrie, a complicated and tragic figure, was one of those folk icons who genuinely appeared to rise up out of the earth from nowhere, born into a sort of boomtown prosperity which was soon shattered by financial disaster, maternal loss, insanity and profound poverty. Seeger was blessed with good genes (his father lived to 92, he to 94), born to a Harvard-educated academic. They were completely different sorts of people and yet connected up in this channel of folk music and radicalism.

Woody Guthrie, 1943

There are so many different Pete Seegers over that span of years and yet all the same. He turns up in freedom movements in all these different places and points in time. You read through the history and think, Wow, he was there, too? Tied in with that movement or effort?

One little nugget: It was Seeger who changed the cardinal lyric from “We will overcome” to “We shall overcome”, which he said “opens up the mouth better.” And if you sing it to yourself you can hear how it does. A tiny little thing, far tinier than most of his achievements. But another of these little centralities. If you look back at the fabric of folk music and 30s labor radicalism, the civil rights movement and modern environmentalism, you see that if you pull the Seeger thread from it the fabric doesn’t quite fall apart but it’s simply not the same.

We all have thoughts and memories and values grafted onto us by our parents, often very early in life and thus in an archaic form. Seeing Seeger in something like hallowed terms is something I got from my father who had a special kind reverence for him, as many people of his generation and outlook did.

Pete Seeger, center, Bruce Springsteen, right, and Seeger’s grandson Tao Seeger, perform Woody Guthrie’s ‘This Land is Your Land’ at the ” We Are One: Opening Inaugural Celebration at the Lincoln Memorial” (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

A highlight for me goes back to President Obama’s first inauguration, a heady time filled with hope and aspiration. As part of the inauguration festivities Seeger, Bruce Springsteen, and Seeger’s grandson Tao sang This Land is Your Land, Guthrie’s best known song which is a sort of – was conceived as a sort of – counter national anthem. And Seeger sang it, as he would, with the more subversive lyrics (which you may not be familiar with) intact.

So here you have Seeger, connecting back to Guthrie and himself an avatar of the Civil Rights Era connecting forward to Springsteen, with his own anthemic qualities and political activism, there singing America’s counter-anthem in celebration of the country’s first black president. There are many currents of what America is. For a certain one, perhaps for many, that was a transcendent moment of connection.