This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

As tractors became more sophisticated over the past two decades, the big manufacturers allowed farmers fewer options for repairs. Rather than hiring independent repair shops, farmers have increasingly had to wait for company-authorized dealers to arrive. Getting repairs could take days, often leading to lost time and high costs.

A new memorandum of understanding between the country’s largest farm equipment maker, John Deere Corp., and the American Farm Bureau Federation is now raising hopes that U.S. farmers will finally regain the right to repair more of their own equipment.

However, supporters of right-to-repair laws suspect a more sinister purpose: to slow the momentum of efforts to secure right-to-repair laws around the country.

Under the agreement, John Deere promises to give farmers and independent repair shops access to manuals, diagnostics and parts. But there’s a catch – the agreement isn’t legally binding, and, as part of the deal, the influential Farm Bureau promised not to support any federal or state right-to-repair legislation.

The right-to-repair movement has become the leading edge of a pushback against growing corporate power. Intellectual property protections, whether patents on farm equipment, crops, computers or cellphones, have become more intense in recent decades and cover more territory, giving companies more control over what farmers and other consumers can do with the products they buy.

For farmers, few examples of those corporate constraints are more frustrating than repair restrictions and patent rights that prevent them from saving seeds from their own crops for future planting.

How a few companies became so powerful

The United States’ market economy requires competition to function properly, which is why U.S. antitrust policies were strictly enforced in the post-World War II era.

During the 1970s and 1980s, however, political leaders began following the advice of a group of economists at the University of Chicago and relaxed enforcement of federal antitrust policies. That led to a concentration of economic power in many sectors.

This concentration has become especially pronounced in agriculture, with a few companies consolidating market share in numerous areas, including seeds, pesticides and machinery, as well as commodity processing and meatpacking. One study in 2014 estimated that Monsanto, now owned by Bayer, was responsible for approximately 80% of the corn and 90% of the soybeans grown in the U.S. In farm machinery, John Deere and Kubota account for about a third of the market.

Market power often translates into political power, which means that those large companies can influence regulatory oversight, legal decisions, and legislation that furthers their economic interests – including securing more expansive and stricter intellectual property policies.

The right-to-repair movement

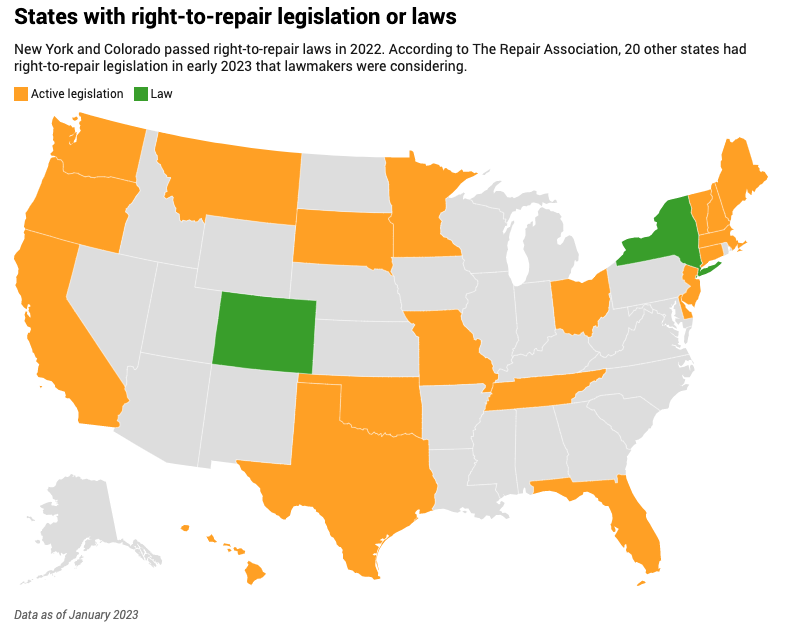

At its most basic level, right-to-repair legislation seeks to protect the end users of a product from anti-competitive activities by large companies. New York passed the first broad right-to-repair law, in 2022, and nearly two dozen states have active legislation – about half of them targeting farm equipment.

Whether the product is an automobile, smartphone or seed, companies can extract more profits if they can force consumers to purchase the company’s replacement parts or use the company’s exclusive dealership to repair the product.

One of the first cases that challenged the right to repair equipment was in 1939, when a company that was reselling refurbished spark plugs was sued by the Champion Spark Plug Co. for violating its patent rights. The Supreme Court agreed that Champion’s trademark had been violated, but it allowed resale of the refurbished spark plugs if “used” or “repaired” was stamped on the product.

Although courts have often sided with the end users in right-to-repair cases, large companies have vast legal and lobbying resources to argue for stricter patent protections. Consumer advocates contend that these protections prevent people from repairing and modifying the products they rightfully purchased.

The ostensible justification for patents, whether for equipment or seeds, is that they provide an incentive for companies to invest time and money in developing products because they know that they will have exclusive rights to sell their inventions once patented.

However, some scholars claim that recent legal and legislative changes to patents are instead limiting innovation and social benefits.

The problem with seed patents

The extension of utility patents to agricultural seeds illustrates how intellectual property policies have expanded and become more restrictive.

Patents have been around since the founding of the U.S., but agricultural crops were initially considered natural processes that couldn’t be patented. That changed in 1980 with the U.S. Supreme Court decision Diamond v. Chakrabarty. The case involved genetically engineered bacteria that could break down crude oil. The court’s ruling allowed inventors to secure patents on living organisms.

Half a decade later, the U.S. Patent Office extended patents to agricultural crops generated through transgenic breeding techniques, which inserts a gene from one species into the genome of another. One prominent example is the insertion of a gene into corn and cotton that enables the plant to produce its own pesticide. In 2001, the Supreme Court included conventionally bred crops in the category eligible for patenting.

Historically, farmers would save seeds that their crops generated and replant them the following season. They could also sell those seeds to other farmers. They lost the right to sell their seeds in 1970, when Congress passed the Plant Variety Protection Act. Utility patents, which grant an inventor exclusive right to produce a new or improved product, are even more restrictive.

Under a utility patent, farmers can no longer save seed for replanting on their own farms. University scientists even face restrictions on the kind of research they can perform on patented crops.

Because of the clear changes in intellectual property protections on agricultural crops over the years, researchers are able to evaluate whether those changes correlate with crop innovations – the primary justification used for patents. The short answer is that they do not.

One study revealed that companies have used intellectual property to enhance their market power more than to enhance innovations. In fact, some vegetable crops with few patent protections had more varietal innovations than crops with more patent protections.

How much does this cost farmers?

It can be difficult to estimate how much patented crops cost farmers. For example, farmers might pay more for the seeds but save money on pesticides or labor, and they might have higher yields. If market prices for the crop are high one year, the farmer might come out ahead, but if prices are low, the farmer might lose money. Crop breeders, meanwhile, envision substantial profits.

Similarly, it is difficult to calculate the costs farmers face from not having a right to repair their machinery. A machine breakdown that takes weeks to repair during harvest time could be catastrophic.

The nonprofit U.S. Public Interest Research Group calculated that U.S. consumers could save $40 billion per year if they could repair electronics and appliances – about $330 per family.

The memorandum of understanding between John Deere and the Farm Bureau may be a step in the right direction, but it is not a substitute for right-to-repair legislation or the enforcement of antitrust policies.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.