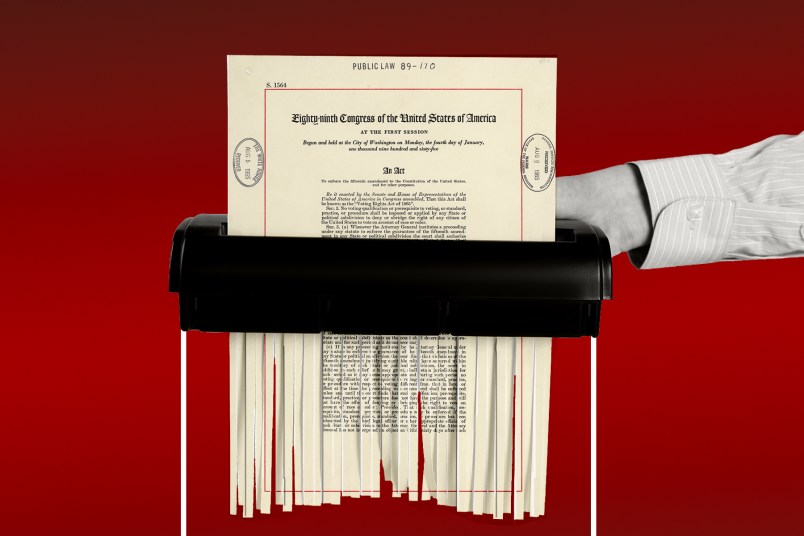

The 8th Circuit Court of Appeals declined to hear a bombshell voting rights case Tuesday, likely putting a case that existentially threatens the Voting Rights Act on track to the Supreme Court.

An 8th Circuit panel had ruled in November that, despite years of precedent, individual voters could not actually bring Section 2 claims under the VRA, the primary method of bringing racial gerrymandering cases at the federal level. Instead, the majority wrote, only the United States attorney general could bring the cases.

The ramifications of this decision, if it continues to hold, are enormous. The vast majority of vote dilution cases under the VRA are brought by individual voters in conjunction with good government and civil rights groups. As one expert told TPM, of the over 200 redistricting cases his organization is tracking following the most recent election cycle alone, the Department of Justice is only involved in three. Under this regime, Republican administrations likely wouldn’t bring any VRA cases at all.

The 8th Circuit is overwhelmingly composed of Republican appointees, with only one active judge appointed by a Democratic president. That judge, Jane Kelly, joined George W. Bush appointee Steven Colloton, who wrote for the dissenters. Fellow Bush appointee Lavenski Smith, who’d dissented at the panel level, also would have granted the rehearing en banc.

“The mistakes in this case are almost entirely judge-driven,” Colloton wrote, singling out both the district judge (a Donald Trump appointee who’d brought up the question of whether individuals could sue under Section 2 himself) and the panel majority that affirmed him.

“The panel’s error is evident, but the court regrettably misses an opportunity to reaffirm its role as a dispassionate arbiter of issues that are properly presented by the parties,” he added.

Colloton echoed many of the arguments Smith had made in his panel dissent, pointing out that Congress had renewed the VRA many times while courts processed VRA cases brought by individuals, and that the Supreme Court, while deciding a case on a different part of the VRA, indicated that Section 2 did have this private right of action. The panel majority had dismissed that Supreme Court record as “mere dicta at most.”

“The panel majority’s unusual notion of ‘dicta,’ and its refusal to treat Morse as controlling precedent for an inferior court, are worthy of further review,” Colloton wrote.

The dissent is also unusually candid about the politics at play, the clear subtext that the right-wing judges are operating under a belief that the new conservative-supermajority Supreme Court might break with what its justices previously thought.

“For this court to proceed on a hunch that a reconstituted Supreme Court would repudiate” those precedential VRA cases, Colloton wrote, “would be too clever by half.”

The plaintiffs in the case may next appeal it to the Supreme Court. The Roberts Court has been legendarily hostile to the VRA, and, over the last decade, has dealt enormous damage to the statute, though it issued a decision supportive of the law last summer that came as a surprise to voting rights experts.

Read the 8th Circuit ruling here:

So lower Court’s get to overrule Supreme Court precedent now too?

I’d love to hear how Alito or Thomas justifies that reasoning.

I’m a bit confused here. Wouldn’t a case like this probably end up before SCOTUS eventually anyway? How does the 8th circuit not hearing it change the eventual outcome in any way?

The Supreme Court can’t hear every case they get a request for each year, so they have to pick and choose which ones. If they decline to hear the case, then the Circuit Court’s ruling becomes the de-facto precedent.

The implication here is that Roberts and Co might decline to take up the case if the 8th Circuit Court ruling (i.e. no private right to sue for VRA violations) is the outcome they want. It’s the sneaky way Court conservatives are using to get their desired policies without the negative headlines for further killing the VRA.

A lot of tepid words that are meaningless in action.

We go to the guillotine on a float of farts billowing from their robes.

Judge-driven mistakes seem to be a calling card of treason party-appointed judges.