A divided federal appellate panel took a pipe to the knees of the Voting Rights Act Monday, handing down an eyebrow-raising decision that would severely curtail the effectiveness of the landmark civil rights law.

Two of the judges on the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals panel — one appointed by Donald Trump and one by George W. Bush — ruled that individuals can no longer bring lawsuits under the VRA. They assert that only the U.S. attorney general can bring enforcement actions under the law.

If the decision holds, VRA cases would nosedive even under Democratic administrations due to limited resources, and would likely stop completely under Republican ones. Currently, voting rights organizations usually collaborate with individual voters to bring VRA claims, one of the last tools with which to challenge gerrymandering on the federal level.

Chief Judge Lavenski Smith, another Bush appointee, dissented and would have preserved the private right of action under the VRA.

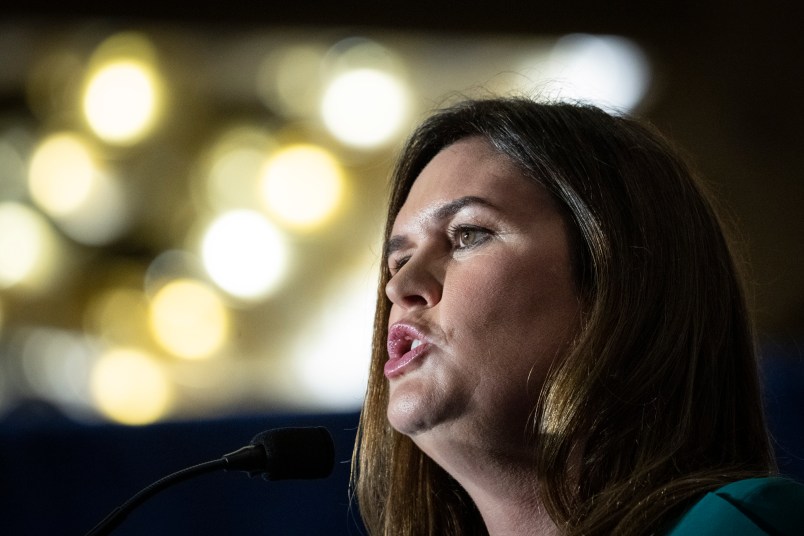

The case originated as a VRA lawsuit brought by the Arkansas State Conference NAACP and Arkansas Public Policy Panel alleging racial gerrymandering in the map dividing the districts for the Arkansas House of Representatives. It names state officials, including Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders (R), as defendants.

Judges Raymond Gruender and David Stras, in changing the nature of the VRA as we know it, rejected both Supreme Court guidance on the topic as well as legislative history. The justices had discussed Section 2 — the part of the law under which vote dilution cases are brought in court — in a 1996 case over a different part of the VRA. They rested that decision on their assumption that the private right of action applied to Section 2 as well.

But that wasn’t enough for Gruender and Stras.

“Taken at face value, these statements appear to create an open-and-shut case that there must be a way to privately enforce § 2,” they wrote. “If five Justices assume it, then it must be true. The problem, however, is that these were just background assumptions — mere dicta at most.”

They also make short work of the legislative history. Both the Senate and House Judiciary Committees in 1982, when Congress amended the statute, wrote that Congress had “clearly intended” for individuals to be able to sue under Section 2 of the law.

“There are many reasons to doubt legislative history as an interpretive tool,” they shrugged, adding: “Nor is it clear how the 1982 Congress could possibly have known what a different set of legislators thought 17 years earlier.”

For Smith, those two data points cut very differently. He wrote that the Supreme Court writings — coupled with Congress’ reupping of the statute without changing it, amid years of VRA cases litigated under the assumption that such lawsuits are allowed — created a weight of precedence.

He asserted that the central question should be left to the Supreme Court, and seemed troubled by how it arose in this case, at the district judge’s own prompting.

“Given the weight of precedent, it is not surprising that the ‘[d]efendants in this case did not initially argue that Section 2 lacks a private right of action until prompted by the district court,’ an issue that the district court raised sua sponte,” he wrote.

The district court judge who raised the question and dismissed the advocacy groups’ case on the basis of the entire category of lawsuits being invalid is Lee Rudofsky, a Trump appointee.

The case will likely reach the Supreme Court, a venue that has been particularly hostile to the VRA under John Roberts’ stewardship, but which batted back a major challenge to the law in a surprising decision last session. The VRA, even one weakened by the Supreme Court, remains so essential to this kind of litigation because the Court shut the federal courthouse doors to partisan gerrymandering cases, leaving only racial ones available.

“Until the Court rules or Congress amends the statute, I would follow existing precedent that permits citizens to seek a judicial remedy,” Smith wrote. “Rights so foundational to self government and citizenship should not depend solely on the discretion or availability of the government’s agents for protection.”

Read the opinion here:

Oh yes, back to the old “states rights vs federal issue” dodge.

Aren’t they concerned we’re going to see through this 3-card monte act after a while?

No! Because of *Supremes” and all that sh!te. Lifetime appointments for federal judges. Yay!

Pushing for that minority rule.

WTF?? What is more sacred and necessary for a functioning democracy than the right to vote?

Of course, it’s always been essential to ensure the “right” people have the right to vote…

John Roberts hates nothing more than when lower courts try to overrule SCOTUS from below. Same 5-4 split as last year’s VRA case, I’d wager.