The Supreme Court asked for an additional round of briefings on what it should do with a major, potentially mooted election law case out of North Carolina over a month ago. Since then, crickets.

The case, Moore v. Harper, grew out of a contested North Carolina redistricting process, but has since become shorthand for the independent state legislature theory (ISLT), a right-wing idea that state legislatures are entitled to sole authority over administering federal elections. A maximal reading of this notion excludes state courts, state constitutions and even governors’ vetoes.

The Court’s May 4 request for extra guidance — its second, after an initial call on March 2 — corresponds with the extraordinary twists and turns the underlying case has taken. During the 2022 midterms, North Carolina Republicans won a lopsided 5-2 majority on the state Supreme Court, the first time they controlled the bench since 2016.

The new, Republican-controlled court wasted little time undoing the work of the former, Democratic-controlled bench. In a nakedly partisan move, they decided to rehear that initial redistricting dispute, in which the old court had struck down the congressional and legislative maps as an unconstitutional gerrymander just a year prior. Surprising no one, this new bench ultimately reversed that decision, despite the fact that none of the underlying facts had changed.

That left the U.S. Supreme Court, which had heard oral arguments in the case in December 2022, in an odd spot. The relitigating at the state level also focused almost exclusively on the maps, and not the ISLT, which barely came up during oral arguments.

The parties in their supplemental briefs urged the Supreme Court in both directions, sometimes creating odd bedfellows as good government group Common Cause and the North Carolina Republican House speaker both urged the Court to decide on the ISLT anyway (Common Cause to avert the issue being decided during emergency 2024 litigation, the speaker because he wants to control elections). Others, including the Justice Department, argued that the Court no longer has jurisdiction over the case.

Since the latest raft of briefings were submitted on May 11, the Court’s silence has become conspicuous. Some legal observers at first predicted it might dismiss the case as moot. But if it was going to do so, we likely would have had that one- or two-sentence order by now.

“The longer this goes, the more likely it is that at least one Justice is writing an opinion,” Doug Spencer, an associate professor of law and election law expert at the University of Colorado, told TPM. “It could be that the Court does dismiss the case as expected, but that one or more Justices dissent from that dismissal and are writing a lengthy dissent laying out their argument. Or it could be that the Court will rule on the merits of the case, with or without a dissent.”

The silence implies that some kind of writing is happening, dragging out the process. The question is what is being written.

“I think one of two things is happening: (1) they’re going ahead and deciding it on the merits or (2) there is at least one justice who thinks they should be deciding it on the merits and so is writing a dissent to the dismissal,” Carolyn Shapiro, law professor and founder of Chicago-Kent’s Institute on the Supreme Court of the United States, agreed.

The ramifications of those two things are obviously very different: A decision on the merits is binding, whereas a dissent to a dismissal is not.

It could also cut in a slightly different way.

“The conventional wisdom is that it’s going to be a lot of concurring-in-the-judgment opinions that nevertheless opine on the merits of ISLT in some fashion,” Jon Sherman, litigation director and senior counsel at the Fair Elections Center, told TPM. “‘If we still had jurisdiction, then ISLT should blah blah blah.’ One would think conservative jurists would adhere to the strict prohibition on issuing advisory opinions when there is no longer a case or controversy.”

Federal courts are not allowed to issue advisory opinions when there’s no case or controversy left to decide.

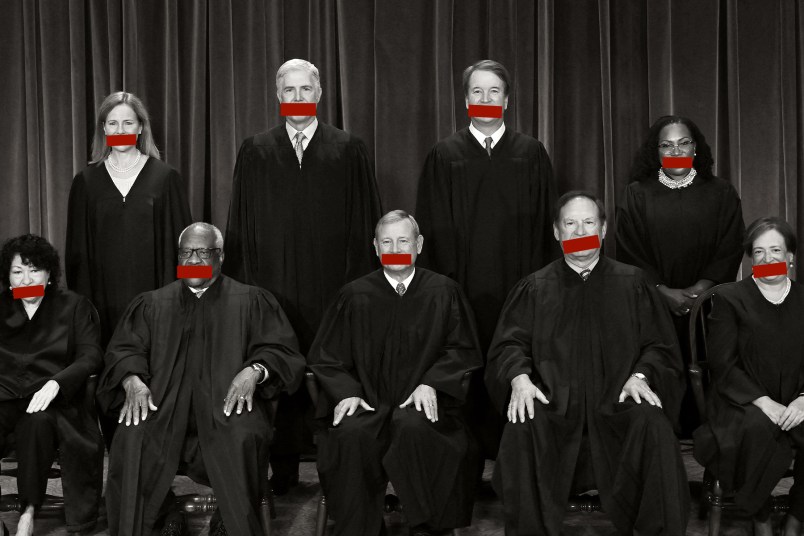

There are at least four justices we know to be amenable to the ISLT to varying degrees, based on their previous writings: Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. That leaves Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett as the potential swing voters.

Both Roberts and Barrett (and Kavanaugh, to a lesser degree) expressed skepticism towards North Carolina’s position during oral arguments, seeming to indicate that they weren’t on board with at least a maximal interpretation of the ISLT. But this case will also come down to the more nuts and bolts question of jurisdiction, and whether the majority thinks it still has any control over this case.

“My own view is the case is dead as a doornail,” Sherman said. “Anything that happens after this point is just Weekend at Bernie’s.”

I’m up way too early. But here’s a lynx.

OT (as if a lynx isn’t), here’s some more bad news for the mango Mussolini:

A continuing legal beat down is just so marvelous.

Ok, maybe this is before caffeine, but what does this mean? “North Carolina” doesn’t have a position in this case. It’s an intrastate dispute. And what is a “maximal interpretation of the ISTL”?

I would think a maximal interpretation of the ISTL means a legislature can do anything they want. But the paragraph before explains the usual suspect regressive justices are fully on-board with ISTL. And since I don’t know who “North Carolina” is in this sentence, I’m left confused as to what oral arguments hinted at with regard to the positions of Roberts and Barrett (and Kavanaugh).

He doesn’t know when to just STFU.

Conservative jurists think about outcomes, not process. If they can deliver an early 2024 win to the GOP, they would do so.