The Supreme Court will hear a case this term that could give state legislatures unprecedented power over federal elections and the laws that govern them.

In Moore v. Harper, North Carolina Republicans argue that the state Supreme Court overstepped its constitutional power when it struck down the legislature’s gerrymandered congressional districts as a violation of the state constitution.

The legislators are arguing that a reading of the federal Constitution — a once-fringe idea called the independent state legislature theory — empowers state legislatures to govern federal elections to the exclusion of state courts, neatly eradicating a critical check on the lawmakers’ power. The state judiciary is particularly indispensable in redistricting disputes, since the Supreme Court barred partisan gerrymandering cases from being heard in federal courts.

But the independent state legislature theory, if accepted by the right-wing majority, would not be confined to redistricting. It rests on a super literal reading of two clauses of the Constitution: The Elections Clause giving state legislatures the power to dictate the “times, places and manner” of holding elections, and the Electors Clause giving state legislatures the power to appoint presidential electors in the “manner” they choose.

Proponents of the theory read the word “legislature” in both clauses to exclude all the other machinery of government around the lawmakers. In maximal interpretations, that means no state court authority over election-related laws passed by the legislature, no governor’s veto, no rule-making by the secretary of state, no voter-passed election initiatives, no restraints from the state constitution, no independent redistricting commissions.

The almighty state legislatures, and only the state legislatures, would get to draw maps, pass election laws, concoct voter restrictions — all with no limitations.

Some fear, in light of the Donald Trump-led efforts to overturn the 2020 election, that this theory could be used as pretext for so-inclined state legislatures to toss out lawfully chosen presidential electors in favor of their chosen slate. This specter looms all the larger given that through gerrymandering, Republicans control, sometimes with supermajorities, the legislatures in many states that wield disproportionate power in choosing the President.

Critics have denounced the theory as completely divorced from the founders’ sentiment towards state lawmakers, as well as farcical on its face: the federal government also gives Congress the power to regulate commerce, but no one reads that writ of power as nullifying the President’s power to veto Congress’ legislation. It also requires some mental contortions to believe that state legislatures are not actually bound by the state constitutions that created them.

Nevertheless, we have data points suggesting that at least four of the Supreme Court justices may cosign the theory. Here’s what we know about what the conservative justices think about the independent state legislature theory:

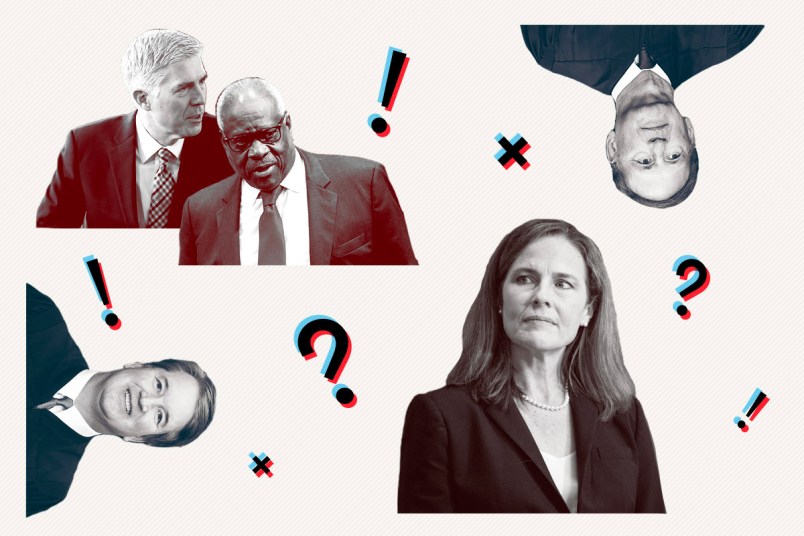

The Fanboys: Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh

These four have left significant evidence in their writings that they support the theory, often urging litigants to get a case before the Court that would let them address it.

Justice Clarence Thomas has been on board since the first time the theory was raised at the High Court, back during Bush v. Gore in 2000.

“In most cases, comity and respect for federalism compel us to defer to the decisions of state courts on issues of state law,” Chief Justice William Renquist wrote in a concurring opinion, joined by Thomas and the late Justice Antonin Scalia, adding: “But there are a few exceptional cases in which the Constitution imposes a duty or confers a power on a particular branch of a State’s government. This is one of them.”

In 2015, Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito both dissented in a case where the majority found that an independent redistricting commission, born from a ballot initiative in Arizona, was constitutional. The Arizona legislature had sued, arguing that it was an unlawful removal of its power over elections.

“If ‘constitutional tradition’ is the measuring stick, then it is hard to understand how the Court condones a redistricting practice that was unheard of for nearly 200 years after the ratification of the Constitution and that conflicts with the express constitutional command that election laws ‘be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof,’” Thomas griped, also using the opportunity to bemoan the right to same-sex marriage handed down in Obergefell just days earlier.

Alito did not write independently in that case, joining instead in a fiery dissent penned by now-Chief Justice John Roberts (more on him later).

But there’s no question as to where Alito stands. His interest in the theory was made explicit in his 2022 dissent from the majority’s decision not to stay a congressional map drawn by the North Carolina Supreme Court (the same dispute that has become the case on the docket now), which was joined by Thomas and Gorsuch:

“If the language of the Elections Clause is taken seriously, there must be some limit on the authority of state courts to countermand actions taken by state legislatures when they are prescribing rules for the conduct of federal elections,” he wrote. “I think it is likely that the applicants would succeed in showing that the North Carolina Supreme Court exceeded those limits.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch voiced his opinion directly too, in a 2020 concurrence over Wisconsin extending its absentee ballot deadlines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The Constitution provides that state legislatures—not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials—bear primary responsibility for setting election rules,” he wrote, waxing lyrical about the state legislature as a more democratic organ than its judicial counterpart.

He was joined in his concurrence by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who has occasionally been a degree more tempered than the other three.

But Kavanaugh also wrote separately in the Wisconsin case, giving the clearest shot at how he feels in a footnote.

“As Chief Justice Rehnquist persuasively explained in Bush v. Gore … the text of the Constitution requires federal courts to ensure that state courts do not rewrite state election laws,” he wrote.

The Conflicted: Roberts

Roberts has been inconsistent in his position on the theory.

In 2015, he attacked the independent Arizona redistricting commission in an opinion that seemed to squarely endorse the idea.

“An Arizona ballot initiative transferred that authority from ‘the Legislature’ to an ‘Independent Redistricting Commission,’” he wrote. “The majority approves this deliberate constitutional evasion by doing what the proponents of the Seventeenth Amendment dared not: revising ‘the Legislature’ to mean ‘the people.’ The Court’s position has no basis in the text, structure, or history of the Constitution, and it contradicts precedents from both Congress and this Court.”

But just four years later, in the infamous case where the conservative majority ruled that federal courts could not hear partisan gerrymandering claims, Roberts pointed to independent commissions as an agreeable option.

“Indeed, numerous other States are restricting partisan considerations in districting through legislation,” he wrote. “One way they are doing so is by placing power to draw electoral districts in the hands of independent commissions.”

Critically, he also explicitly expressed his approval of state courts’ role in adjudicating such cases.

“Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” he wrote.

The Mystery: Barrett

Justice Amy Coney Barrett is the only justice in the conservative majority who has not opined on the theory.

As Dave Daley, former editor of Salon and author of two books on redistricting and voting rights, told TPM: “A lot is riding on how Justice Barrett views decades of judicial precedent and her love for free and fair elections in a representative democracy.”

I liked this article… but there is one thing that could have been added that would give a really good view as to how they conservatives might rule:

What does Leonard Leo think?

Yes the man of power behind the SC.

Why should the Court care about niceties like checks and balances when it has the power to enshrine permanent (Republican) minority rule?

Hello? Supremacy Clause calling!

Welcome to the Independent States of America!