As Republicans came before the Supreme Court Tuesday to get rid of one of the last regulations governing our wild west campaign finance system, the colloquies fell flat.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor took on the “slippery slope” role. She reminded listeners of the Watergate-era corruption that gave rise to the regulation that the petitioners in this case, the National Republican Senatorial Committee and JD Vance, want to do away with, and how little will be left if the limits on these donations to parties are wiped away too. But it had the feel of a skirmish after the war had already been lost.

This Supreme Court has obliterated campaign finance regulations, most notably through Citizens United, which flooded our elections with dark money and gave rise to monstrous Super PACs that donors can give to in unlimited amounts with very little transparency. (Justice Samuel Alito complained Tuesday that the infamous decision has been “much” and “unfairly maligned.”)

Tuesday’s case, NRSC v. FEC, deals with how much donors can give to parties for coordinated expenditures with the candidate, and in this landscape, feels almost quaint. (Vance was left over on the case after his 2022 primary run when he struggled to raise money from all but mega-donors like Peter Thiel.)

And even within these dregs of campaign finance regulations that still remain, the Court has limited its interest in corruption and bribery to quid pro quo arrangements. As Sotomayor scathingly pointed out, the barrier against even that myopic category of bribes is flimsy.

“You mean to suggest that the fact that one major donor to the current president — the most major donor to the current president — got a very lucrative job immediately upon election from the new administration does not give the appearance of a quid pro quo?” Sotomayor asked former Trump Solicitor General Noel Francisco.

After feigning confusion about who she was referring to, Francisco implied that Elon Musk’s government paycheck paled in comparison to his endless wealth, which Sotomayor cut across, pointing to his government contracts.

The liberals went through the motions, Justice Elena Kagan pointing out that parties, unlike Super PACs, can coordinate directly with candidates, so nixing the restriction would give donors an advantage they don’t currently have.

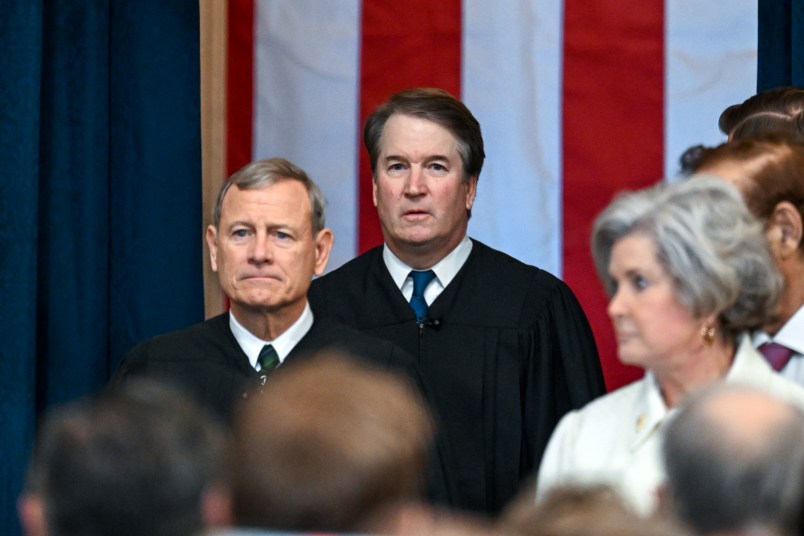

One of the more interesting discussions came from an unlikely source, as Justice Brett Kavanaugh started a conversation with Francisco about whether he’d be back in a year to challenge the other remaining restrictions he said would mitigate the danger of getting rid of the coordinated expenditure limits.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson picked up on the thread: “In McCutcheon, your clients filed a brief saying the sky wouldn’t fall if the Court struck down aggregate limits because we still have coordinated expenditure limits, and now here we are today with your clients saying no more coordinated expenditure limits. And so I’m wondering if, and others have sort of raised that concern as well, we’re gonna be back here with the other kinds of limits with you making the same kinds of arguments.”

Still, the odds that the Court’s right-wing majority will rouse itself to care about abuse in campaign finance now cut against years of work in the opposite direction. Alito complained later on in the arguments that Kavanaugh and Jackson’s concerns about the continuing pattern of incrementally fighting regulations was “speculative” and not something the Court should consider.

Sotomayor captured the lay of the land best when borrowing a metaphor from her “sister,” the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She compared campaign finance regulations to an “umbrella,” arguing that the lack of evidence of bribery was proof that the regulations work, not a reason to toss away the umbrella in a rainstorm.

Ginsburg initially penned the line when the Court struck down a key component of the Voting Rights Act, ushering in a flood of voter restrictions that profoundly distorted American democracy. The Court heard a different case this term that could render the landmark civil rights act just as toothless as campaign finance restrictions, another resounding legacy of the Roberts Court.

The legacy of the Roberts court will in large part be ensuring the primacy of money, and those who have it, over all the other considerations of a civil society.

Once, just once in my lifetime I want to read about an other Justice turning to Alito and saying, “Jesus Christ, you insufferable snot-goblin, you really are an asshole.”

It’s one thing to be a part of some of the decisions which have most harmed American democracy but it takes a special type of arrogance for him to then act as though everyone else is too stupid to understand how great those decisions really were.

I still fail to understand the dubious logic that money is the equivalent of speech. More money = more undue influence = more corruption, in my thinking.

Add to $$$$ = speach, corporations are people.

ETA. Santa Clara County vs Southern Pacific RR, 1886(?). The height of the gilded age. We are in the same place today.

Yes, Mitt Romney, aka “Etch-A-Mitt” reminded us of that!