This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

The death of Jean-Marie Le Pen, former leader of the party once known as the National Front, occurs at a time when the mainstreaming of far-right politics in France seems almost complete.

Le Pen was, for most of his career, considered the devil in French politics. Yet today, his party, headed by his daughter and now called National Rally (Rassemblement National), is at the gates of power.

Le Pen became an MP in France’s national parliament in 1956, when he was just 27. He quickly became the face of the extreme right. After leaving for Algeria to fight against independence and being accused of torture during his military service there, Le Pen returned to French politics in the 1960s.

This was a time of social progress – and therefore a nadir for far-right politics.

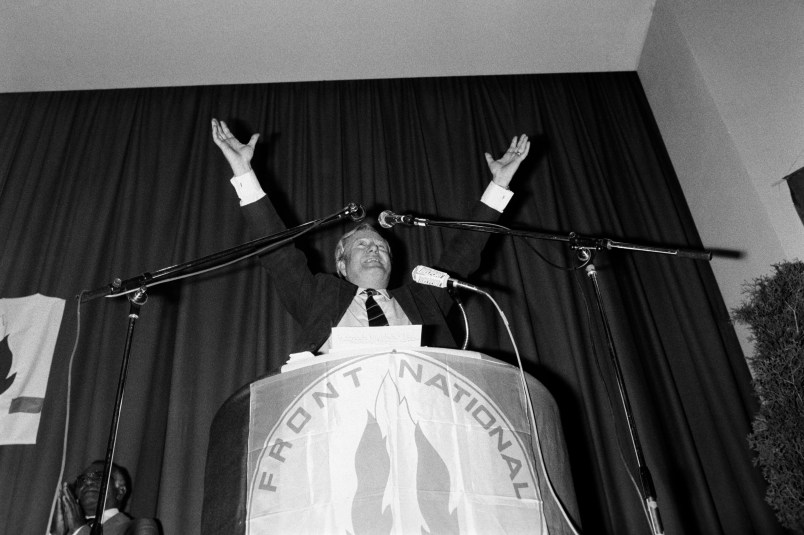

In 1972, Le Pen was part of the group that created the National Front – essentially an attempt to unite various small extreme right organisations under one banner. He became the party’s first president as he was considered the least extreme of the contenders.

This was despite his having been found guilty of war crime apologia in 1971 for republishing a vinyl record of Nazi songs. Le Pen also routinely demonstrated a nostalgic attachment to the Nazi-collaborating Vichy regime of second-world-war France.

Racism was always at the core of Le Pen’s politics. However, as his party sought mainstream acceptance, the core became thinly concealed under veneers of anti-immigration concerns, patriotic pride or even pretence of defending women and France’s system of laïcité (secularism) against Islam.

The beginnings of the National Front were slow and the party struggled to be noticed until the mid-1980s. Its first national breakthrough was greatly aided by Socialist president François Mitterrand, who had been elected in 1981 on a radical platform but quickly turned to austerity to respond to a developing financial crisis.

Mitterrand’s approval ratings took a tumble as a result and, to stem the resurgence of the more moderate right, he actively and consciously helped Le Pen’s then-struggling party. With a view to splitting the vote on the right, Mitterand lent legitimacy to Le Pen’s extreme ideas by giving him a platform on public national media in particular. Most cynical of all, Mitterand changed the electoral system to a proportional one, which gave the National Front 35 MPs and a huge boost in visibility.

2002: Le Pen in the second round

Yet the real shock was to come in 2002 when Le Pen reached the second round of the presidential election. Here again though, this said far more about the state of French politics and democracy than it did of the so-called “irresistible rise” of the National Front.

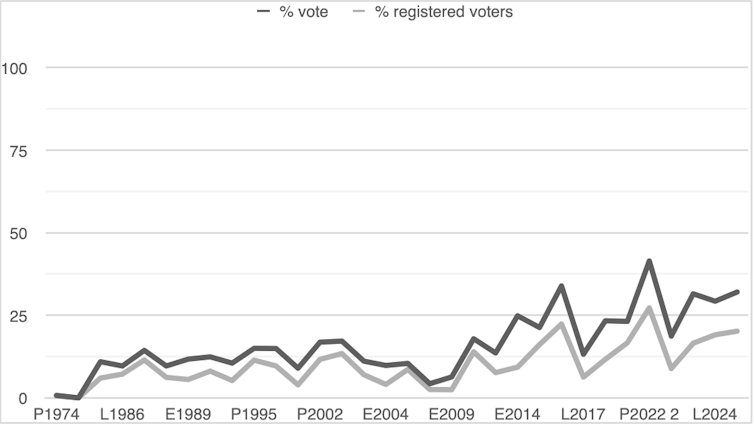

Le Pen’s actual vote had been stagnant since 1988. Although the Le Pen vote appeared to increase by 2.5% between 1988 and 2002, when turnout is taken into account, his share of the vote increased only by 0.19% – or less than 500,000 votes. This is certainly not negligible but far from the perceived “tidal wave”.

Instead, it was the growing unpopularity of the status quo and the major governing parties which paved the way for the earthquake. In 2002, the major centrist parties on the left and right collectively received fewer votes than the abstention rate.

Likewise, perspective is also needed on the 2007 election, which has always been depicted as Le Pen’s downfall and the triumph of the mainstream over the extremists. In reality, Nicolas Sarkozy had siphoned a significant portion of the far-right vote by openly positioning himself as direct competition to Le Pen. Sarkozy’s constant attacks against immigration and Islam earned him the nickname “Nicolas Le Pen” in the Wall Street Journal.

As Marine Le Pen, Jean-Marie’s daughter and – at the time – campaign director, said on the night of the first round when asked how bad a defeat this was: “This is the victory of his ideas!”

So while Jean-Marie Le Pen was seeking to render his politics more palatable by moving away from his most incendiary discourse, the mainstream parties were helping his cause by taking an ambivalent attitude towards his messaging in order to win back his voters. Le Pen also provided a welcome diversion away from the crises mainstream parties proved unable to address.

This situation continued to worsen as Marine Le Pen replaced her father as party leader in 2011. She eventually changed the name of the party to National Rally and evicted him in 2015 when she could no longer defend his comments about gas chambers being a mere “detail” of the second world war.

But by then Sarkozy had mainstreamed much of the FN’s discourse. The election of Socialist François Hollande as president did nothing to turn the tide in 2012 as he also tried to act “tough” on the far right’s pet issues, including immigration and Islam in response to a deadly wave of terrorist attacks.

Arguably no president, however, has proven as zealous as Emmanuel Macron in his attempts to defeat the far right by absorbing its discourse, while claiming to be a bulwark against it. In 2020, he appointed an interior minister who accused Le Pen of being “too soft on Islam”. This marked a new low – the mainstream was outbidding rather than mimicking Le Pen.

2024: a dynasty at the gates of power

Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen has benefited not only from the mainstream’s pandering to her own politics but the hype around her rival on the far right, Eric Zemmour, during the 2022 presidential election campaign. The heightened attention devoted to Zemmour effectively obscured the genuine threat posed by Le Pen and her far-right ideology, which, by comparison, appeared almost moderate and reasonable.

Now, Le Pen, despite being embroiled in a damaging trial, appears the de facto kingmaker, supplying the votes Macron’s government needs to survive in a fractured parliament.

The death of Jean-Marie Le Pen occurs therefore at a time when French politics is facing one of its worst crisis. Far from being a bulwark against the far right, Macron has paved the way for the National Rally by mainstreaming its discourse and politics.

As much of the mainstream elites seem to have accepted that the rise of the far right is irresistible, the only choice left is whether it will be the far right or mainstream politicians implementing far-right politics. These are the options: the bad and the worse. That is until France takes seriously the threat posed by the far right and the need for a radical change.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Some people make the world a better place only when they leave it.

https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/oscar_wilde_100487

As the US is on the cusp of the end of it’s first Republic, the French are racing ahead to their 6th? Let’s all slow down a little bit in this horse race, fellas.

“…the mainstreaming of far-right politics in France [seems almost complete…”

These guys don’t create the right-wing sentiments in their respective countries – France, USA, and earlier, Germany.

They make what we call bigotry, xenophobia, racism, misogyny “legitimate”. Here in the US, the rump victory twice tells us that about half of our citizens are willing to elect an ascendent autocrat. Come out of the closet and I’ll perform some genocide-lite by stuffing people you despise into busses and trains and dumping them in a neighboring country. Some of our followers would like to gas them, but we’ll just exile them.