ATLANTA, GEORGIA — When Georgia State University student Nicholas Perry went to vote for the first time at Atlanta’s Liberty Baptist Church on Election Day, he didn’t understand why poll workers made him cast a provisional ballot. His address on file was for his home in Dacula, Georgia, he was told, but Perry said he had updated his registration to his campus address.

He tried to argue, but the line of people waiting to vote was long and the poll workers’ patience was limited. Even worse, nobody could help him. The poll workers were confused, Election Protection attorneys volunteering to monitor the polling place were confused, and he was confused.

He left the church unsure what a provisional ballot was, why he was given one, and whether his vote would count.

He wasn’t alone. I spoke with many students who cast provisional ballots at the same polling place, and few understood why. Across Georgia, tens of thousands of people experienced problems registering to vote and casting a ballot. Georgia’s election laws were complicated, and voting policies were changing right up until the day of the election. As the votes were tallied and the margin between the two candidates for governor, Democrat Stacey Abrams and Republican Brian Kemp, narrowed, many voters remained unclear whether their ballots had counted. Even more questioned whether the election was legitimate.

As laws making it harder to vote spread across the country, an additional and often unnoticed barrier comes with them: confusion. Georgia wasn’t the only state that created chaos and uncertainty at the ballot box. Similar scenarios played out this year in parts of Missouri and Florida. Two of 2018’s most competitive gubernatorial elections may have swung on voter confusion.

“Anything that causes confusion is a form of voter suppression, whether it’s intentional or whether it’s just unintended consequences,” said Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, a nonprofit organization focused on voter outreach across the South.

The United States’ byzantine election system is governed by overlapping rules on the county, state, and federal levels. Elections in different states and even different cities are held on different days, with polling places in varying locations and voting hours that change from one year to the next.

Together, the laws and procedures result in a chaos that undermines faith in election, and that is easily exploited by politicians in the name of election integrity.

“The confusion creates this fog that then opens up the doors for more blatant forms of suppression,” Albright said. In recent years, strict voter identification laws, the substantial reduction of polling locations and voting hours, and massive purges of voter rolls have all resulted in more confusion.

And while solutions exist, they aren’t always put into practice. Instead, Republicans tout laws they claim combat voter fraud — a problem that is vanishingly rare. Those laws both directly suppress voters and complicate elections to the point where confusion becomes an additional voter suppression tactic, said Rick Hasen, a voting rights expert and professor at the University of California Irvine.

“The more complicated you make things out of a desire to secure the integrity of the process — or at least that’s the claim — the greater the risk, if the rules are complex, that voters and election officials are not going to understand them,” Hasen said.

With hurdles to voting come confusion. This has been the case since a very early hurdle, voter registration, was put in place in the second half of the nineteenth century. As Greg Downs, a history professor at the University of California, Davis, wrote in the first piece of this series, registration alone was enough to dramatically decrease the participation of racial and ethnic minorities.

In the 21st century, lawmakers — specifically, Republicans crying fraud — have sought to put in place new and creative hurdles to casting a ballot. One of the most popular obstacles used in recent years is voter ID. And with each new hurdle comes incidental, or intentional, confusion.

A total of 34 states have laws requiring voters to show some form of ID when they cast a ballot. Research shows that roughly 11 percent of the U.S. population doesn’t have the necessary ID, and that number is even higher among seniors, people of color, people with disabilities, low-income voters, and students.

Many of the restrictive laws have been passed since 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court eliminated the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement. When the requirement was still in place, the Department of Justice had to approve new voting laws from states with a history of discrimination. Now, advocates are forced to challenge the restrictions after they became law.

Civil rights groups have done just that, using the other provisions of the VRA to challenge many of the new voter ID laws in court. Before judges across the country, the organizations have argued that the laws are discriminatory, unconstitutional, and unlawful.

Often, litigation comes down to the wire before critical elections, with groups on both sides filing last-minute emergency motions, seeking to have their way before Election Day. Just this year, a Missouri judge issued a ruling less than a month before the state’s critical Senate election, blocking part of the state’s voter ID law and finding that state officials couldn’t tell voters that they had to show a photo ID to cast a ballot.

Such legal battles, which are aimed at making it easier to vote and reducing the potential for voter confusion, can sometimes contribute to it. On Election Day, ProPublica and the Huffington Post reported that poll workers incorrectly turned voters away for not providing a photo ID. Signs still hung at polling places with the outdated requirements, and voters said they had to argue with election workers in order to cast ballots. County supervisors reported being understaffed and having minimal time to train poll workers on the changed law.

“We did everything we could given that we were on such short notice,” Franklin County Clerk Debbe Door told ProPublica. “We’ve got election judges that are 70 or 80 years old and we threw something new at them without an opportunity to train.”

This situation is not unique. Courts often introduce new confusion with last-minute rulings before an election.

“Change in itself is a problem,” Hasen said. “Even the Supreme Court has recognized that confusion itself can be a form of disenfranchisement.”

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on the issue of last-minute legal changes and the potential for confusion. In Purcell v. Gonzalez, the high court ruled that an appeals court was incorrect to grant an injunction against the enforcement of Arizona’s photo ID law on October 19, shortly before an election. The court cited the “imminence of the election.”

“Court orders affecting elections, especially conflicting orders, can themselves result in voter confusion and consequent incentive to remain away from the polls,” the court wrote in its opinion. “As an election draws closer, that risk will increase.”

Since then, the Supreme Court has abided by the Purcell principle, frequently deciding not to issue orders that change election rules in the period just before an election.

Given the Court’s precedent on last-minute changes and the potential for voter confusion, voting rights groups have to weigh the risks before they bring litigation seeking to change election laws before an election. It presents a tradeoff: Will the laws they’re challenging disenfranchise more people than the confusion that could result from a last-minute change in the law? Sara Henderson, the executive director of Common Cause Georgia, said her group often debates that decision.

“I feel like litigation is a double whammy, and we use it as a last resort because it does create confusion,” she said. “I’ll also go so far to say it does suppress turnout.” Voters, she said, “hear all of these decisions about votes not being counted, machines not working properly, and so it comes to the public and they look around like, ‘What do we do?’”

Myrna Perez, the deputy director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s democracy program, represented Common Cause in its request for a temporary restraining order in Georgia days before the midterm election. (A judge ultimately agreed that Kemp demonstrated a “failure to properly maintain a reliable and secure voter registration system” and barred the state from certifying the election until all rejected provisional ballots were reviewed.)

Perez agreed that some last-minute legal requests are harder to fulfill than others. Often, like in Georgia this year, the need for litigation in order to secure the right to vote for vulnerable populations wins out. “In the case that we filed, in the relief that we got, the judge was very, very concerned,” she said.

This need has been especially acute since preclearance ended and groups were put in a reactionary position, needing to challenge laws that they claim never should have been allowed in the first place.

“We don’t want to file litigation,” Henderson, of Common Cause Georgia, said. “It’s expensive and a waste of resources, but they really leave us no choice but to do it.”

Ahead of the November election, Georgia became what many were calling “ground zero” in the battle over voting rights. In October, the AP reported that Kemp, then the secretary of state, had marked roughly 53,000 voter registration applications as pending because the information on their registration applications didn’t exactly match the information on file with state agencies. Around 70 percent of the pending applications, the AP said, belonged to black voters. Advocates expressed concerns that voters would get to the polls, unaware that they weren’t eligible to vote.

In response to those concerns, groups including the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda and the New Georgia Project filed a last-minute lawsuit on October 11 seeking to block Kemp from purging people from the rolls. Just five days before Election Day, a federal judge issued a last-minute injunction, allowing some of the purged voters to be eligible to cast ballots.

But five days left little time for the state to communicate the changes to the counties and poll workers running the election, many of whom were trained according to previous standards months before the rulings came down. Without state action, advocacy organizations often attempt to do the work themselves.

“Voters were showing up to the polling places and poll workers weren’t even aware that they needed to check a separate list of pending registrations,” Henderson said. As a result, voters had to argue with their poll workers in order to cast a ballot, exacerbating their confusion.

Part of the issue was that even the court ruling was confusing. People whose registrations had previously been purged could cast regular ballots if their ID’s showed a “substantial match” with what was on the state’s voter roles. That term was not defined by the court. “I don’t know how many of those that showed up were properly handled when it comes to this ‘substantial match’ makeshift rule,” he said.

An unknown number of voters were also forced to cast provisional ballots, including many Atlanta-area students like Perry. Voters, poll workers, and election protections volunteers were all unclear what would happen with provisional ballots. Some voters were told that if they voted out-of-precinct, their votes for statewide office would count, but that turned out to be false.

Georgia State University student and 18-year-old Noelle Higgins said poll workers initially told her she’d have to cast a provisional ballot because her student ID wasn’t a valid form of voter ID. “They told me I couldn’t vote because it didn’t have my birthdate on it,” she said.

In Georgia, student IDs from many schools, including Georgia State, are a valid form of ID to cast a ballot.

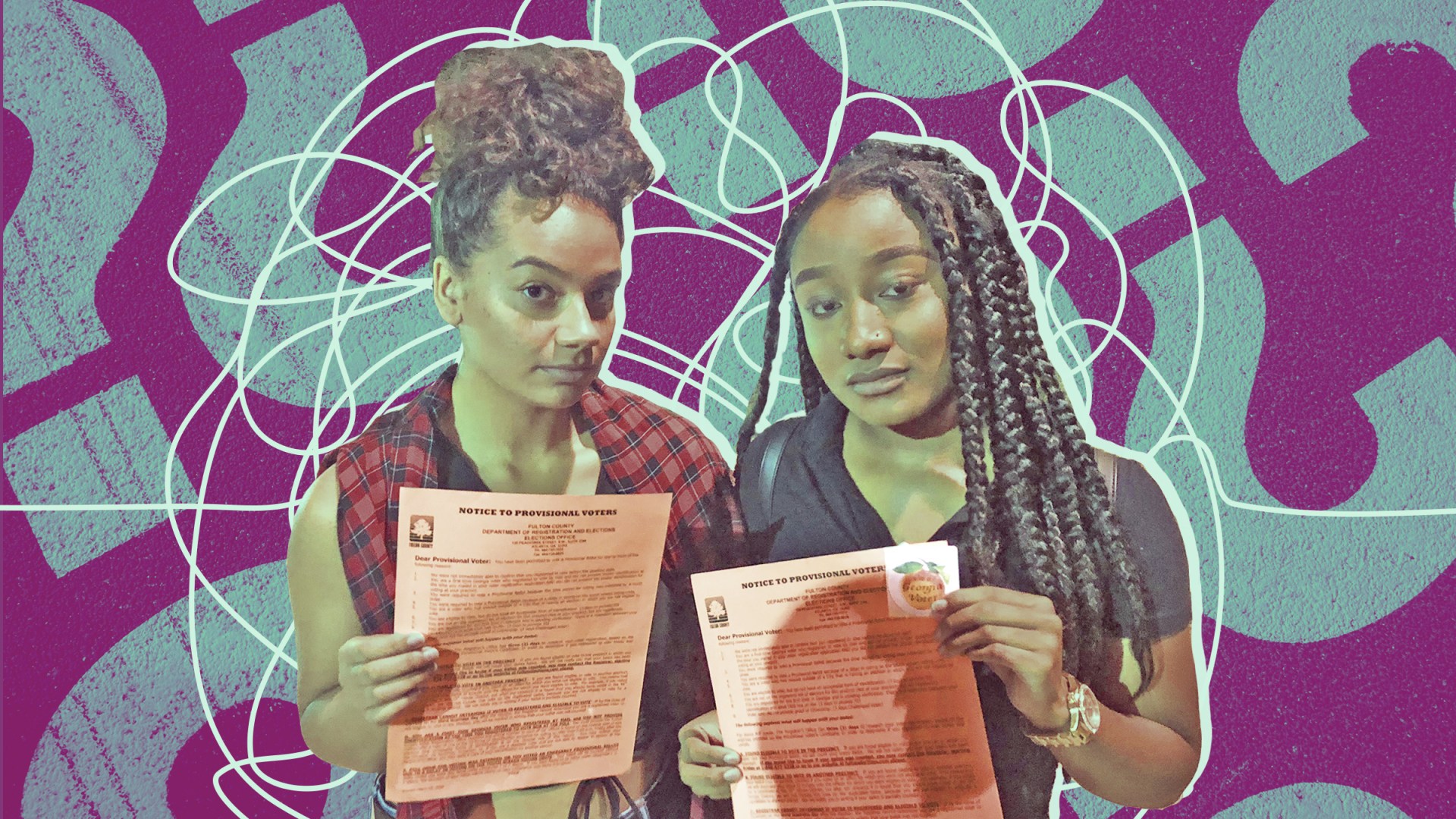

“So I came out here to the election representatives and they sorted it out so I could vote,” Higgins told me. She was able to cast a regular ballot thanks to Election Protection volunteers, but I watched many like her leave polling places in Atlanta with orange papers in their hands — the telltale sign that they were forced to vote provisional (Poll workers gave an orange paper to provisional voters that explained how they could follow up to make sure their votes counted.)

At the Atlanta University Center — the home of the historically-black Clark Atlanta University, Spelman College, and Morehouse College — many young voters left their polling place and walked across the leafy green campus clutching their orange papers. None could explain why the weren’t able to cast regular ballots.

.@joshua_eaton and I are spotting students with these orange papers — provisional ballot info — across Atlanta. These two Clark Atlanta University students say they registered at their campus address but we’re forced to vote provisional anyway pic.twitter.com/ExOFKxGWnF

— Kira Lerner (@kira_lerner) November 7, 2018

“The laws are so confusing and change so much that even our poll monitors have a hard time deciphering all the ins and outs,” Henderson said. “Let’s be honest, if you’re a poll worker at a polling place on Election Day with two to three hour lines and you’re tired, the easiest solution is to offer a provisional ballot.”

In other parts of Georgia, voters had to wait four and a half hours to cast ballots because of broken machines. Some of them left their polling places, expressing concern about the situation and whether the lines would be shorter later in the day.

Georgia was also unique because advocacy groups claimed that Kemp, the state’s elections director, was ignoring his duties as secretary of state in order to run for governor. Kemp dismissed the claims. “People lose sight that the counties run the elections. They’re counting the votes, they’re tabulating, they’re uploading them to our site,” he told the Atlanta journal Constitution. “None of them brought this up in 2010 or 2014. So what’s changed now?” Kemp did eventually resign — but only after declaring victory, and once a lawsuit by the group Protect Democracy demanded his recusal.

In the days after the election, before the race was officially called, Abrams’ campaign continued to speak out about the number of uncounted provisional ballots that could force the race into a recount or a runoff.

Later, after Abrams conceded, she launched a new organization that almost immediately filed a lawsuit seeking to overhaul the state’s elections. Unlike other lawsuits which target specific laws or elections rules, Abrams’ organization’s lawsuit claims that the state “grossly mismanaged” the entire election, causing low-income citizens and people of color to be denied their right to vote.

While the complaint doesn’t specifically discuss voter confusion, Abrams’ campaign manager and Fair Fight Georgia CEO Lauren Groh-Wargo said it’s at the heart of all of it.

“The 2018 Georgia elections were marred by the Secretary of State’s gross mismanagement of our elections, leading to mass confusion for voters in communities across the state and large scale irregularities that trampled Georgian’s constitutional right to vote,” she said.

In Georgia and Missouri, voter confusion was caused by lawmakers and elections officials who purposely passed laws making it more difficult for certain voters to cast ballots and the legal battles that followed. In other words, the confusion was intentional.

Often, though, confusion is caused unintentionally.

“Much of the reason that voters end up being disenfranchised, or not casting an effective vote, has nothing to do with intentional actions on the part of Republicans or any others to stop them from voting, but has to do with incompetence in the election system,” Hasen said.

In Broward County, Fla., for example, elections officials designed the ballot for the November 2018 election with the Senate race tucked in a corner under the instructions, which many voters overlooked. According to MCI Maps, about 3.7 percent of voters — 30,896 people — skipped voting for U.S. senator. That number is as much as 2.5 percent more than in most other counties, according to the a column in the Washington Post by the co-founders of the Center for Civic Design, a non profit that advises elections officials on ballot design. The authors noted that in Broward County, more people voted for the commissioner of agriculture and county CFO than for their U.S. senator.

The number of votes separating former Sen. Bill Nelson (D) and Rick Scott, who ultimately won, was far smaller than the number of people who skipped voting in the race. Many questioned whether poor ballot design, and the resulting voter confusion, ended up costing Nelson his seat in the Senate. But that confusion was likely unintentional, Hasen said.

“I haven’t seen any indication that [Broward County Supervisor of Elections] Brenda Snipes or any other Broward official were trying to discourage people from voting in the Senate race by hiding the Senate race in the corner,” he said.

Hasen said he usually explains this phenomenon using the principle of Hanlon’s razor. “Don’t attribute to malice that which can be explained by incompetence, and there’s plenty of incompetence to go around,” he said.

But the confusion was still avoidable, especially given Florida’s history of poor ballot design. In the 2000 election, the now infamous “butterfly ballot” left many voters confused and caused some who intended to vote for Democrat Al Gore to instead vote for Pat Buchanan, a conservative third-party candidate.

Given past challenges, especially in Florida, the Brennan Center’s Perez said that localities and states should do a better job to test their ballot design and election materials for usability.

“This is not rocket science,” she said. “Not only are there knowable conventions — things that more often than not are going to be the right way to handle it — it’s also not impossible to test it.”

Issues like those in Broward County this year point to how many different kinds of problems cause confusion, and how many different kinds of problems need to be addressed.

“There are some that are just straight-up intentional suppressing of certain communities,” Perez said. “There’s mistakes that are made because people are not resourced or they’re not trained or they’re moving too quickly and they don’t have enough fact checks. And then there’s this third category of mistakes that happen when folks are told they’re going to have these types of problems and they don’t invest the resources anyway.”

“At what point does it actually become something close to intentional for them not to do something about it?” she asked.

Of all the issues with U.S. elections, the fact that voters are disenfranchised by a confusing system might be the hardest to fix. After all, confusion is both a byproduct of a broken election system and a deliberate mechanism of restricting the electorate.

Confusion stems from countless poorly designed laws and regulations on the local, state, and federal level. It stems from poorly trained poll workers and understaffed election departments. It stems both from lawmakers who wish to confuse and lawmakers who want to undo that confusion and end up causing even more in the process.

Together, it’s resulted in a country where voters have lost faith in elections.

Still, experts say solutions are possible. One major way to simplify elections, and to create fail-safes for voters who might be confused, is to expand opportunities to cast ballots. That includes lengthening early voting periods and hours and allowing people to register to vote on the same day that they cast a ballot.

Currently, 17 states and the District of Columbia offer same-day registration and three more states plan to implement it soon. Evidence shows that allowing voters to register on Election Day increases turnout, as voters — especially those who may be confused about deadlines — are offered the chance to remedy any registration issues when they cast a ballot.

Automatic voter registration provides another way to simplify elections. If eligible citizens are automatically added to the rolls when they turn 18, they no longer will have to worry about figuring out the steps needed to ensure that they are on the rolls.

Like same-day registration, automatic registration is slowly spreading across the country. Currently, 16 states and the District of Columbia have authorized automatic registration. Advocates say the reform will increase turnout, although there’s not enough evidence yet to know for sure.

Voters will also have to elect elections officials who prioritize access to the ballot, rather than fearmongering about nonexistent voter fraud. States and localities need to invest money in elections and treat them with the same level of seriousness as other critical government services. And advocates will have to remain vigilant, challenging provisions that might confuse and conducting educational campaigns to ensure that voters are as informed as possible heading into an election.

“There’s not going to be one silver bullet,” Perez said. “It’s a bunch of silver bullets.”

When asked about potential solutions, Albright, of Black Voters Matter, laughed. “Just revamping all of American democracy, no big deal,” he said. He explained that first and foremost, Americans need to recognize that elections can and should be less complicated.

“In what’s supposed to be the greatest democracy in the world. This just shouldn’t exist.”

Kira Lerner is a reporter for The Appeal focused on criminal justice, voting, and civil rights issues.

Made possible by