On March 13, 1902, as the Alabama River began to rise, a black middle-aged postal clerk named Jackson Giles tried to convince three white registrars in Montgomery, Alabama to add his name to the rolls. Giles had been voting for years, but under the new constitution passed to “establish white supremacy in this State,” he had to register anew. To exclude voters, the constitutional convention turned to literacy tests, poll taxes, felony exclusions, grandfather clauses, and lengthy residency requirements, but perhaps no single measure did more ruthless work than the requirement to register anew. In many ways Jackson Giles was precisely the kind of man of “good character” that the voting “reform” contemplated: a father of two daughters and a son, a widow, a taxpayer, and, newly, a husband to his second wife, Mary. But the registrars turned him out anyway; in Alabama, the criteria for good character was white skin.

Like many other aspiring Montgomery African Americans, Giles lived in a house in Centennial Hill, less than a mile from the state Capitol. Back in February 1861, when Giles was a toddler and a slave, Jefferson Davis moved near those Capitol grounds into the “First White House of the Confederacy” until he, his family, and the Confederate capital decamped in May for Richmond, Virginia. Seventeen years after Giles tried to register to vote, the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church bought a cottage around the corner from Giles’ Watts Street residence, and in October 1954 a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. moved his family into that small house. In January 1956, the neighborhood shook. Terrorists opposed to the Montgomery Bus Boycott had bombed the parsonage while King spoke a mile away at the Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s First Baptist Church.

In 1902, almost exactly halfway between the slaveowners’ rebellion that brought Jefferson Davis to Montgomery and the Civil Rights Movement that apotheosized Martin Luther King Jr., Jackson Giles fought to defend his right to vote. Because of the detective work of historian R. Volney Riser, we know some precious details about the steps he took in the weeks after the registrars refused to enroll him. In late March 1902, as the Alabama River rose 12 feet above the “danger line,” washing out farmland and railroads across the region, Giles and fellow postal clerks James Jeter and Edward Dale created a new organization, the Colored Men’s Suffrage Association of Alabama, to raise funds to take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Already it was clear that Alabama’s registration system had worked all too well. Black registration had fallen to fewer than 3,000. Even 40,000 white men had failed to register. Voter turnout, already declining due to 1890s “reforms,” dropped from 162,302 to 91,863. On its official ballots, the State of Alabama soon printed the Democratic Party motto: “White Supremacy.”

The starkness of those declines makes it easy, too easy, for Americans to talk about Jackson Giles’ story as something that only happened to black Southerners. When Americans treat voter disfranchisement as a regional, racial exception, they sustain their faith that the true national story is one of progressive expansion of voter rights. But turn-of-the-20th-century disfranchisement was not a regional or a racial story; it was a national one. Even though rebels perfected the art of excluding voters, it was yankees who developed the script. During the 1901 convention, Alabama delegates circulated copies of Massachusetts’ voting laws with the Bay State’s grandfather clause, literacy test, registration requirement, and secret ballots, all intended to make voting more difficult for immigrants. These Massachusetts laws worked, if not quite as well as they did in Alabama; voter turnout fell from 55 to 41 percent.

[ Gregory Downs discusses this essay on the Josh Marshall Podcast ]

The tools that broke American democracy were not just the Ku Klux Klan’s white sheets, vigilantes’ Red Shirts, and lynch mobs’ nooses; they were devices we still encounter when we vote today: the registration roll and the secret, official ballot. Along with exclusions of felons and permanent resident aliens, these methods swept the entire United States in the late 19th century, reducing nationwide voter participation from about 80 percent to below 50 percent by the 1920s. Despite the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and increasing voter mobilization, turnout in the United States has never recovered; by one 2018 survey, the country ranks 26th of 32 developed democracies in participation.

To understand how voting shrank, we first need to examine how it expanded. The answer used to seem as clear as the image on the twenty dollar bill: Andrew Jackson. The story went like this: the Constitution created a republic, but the Jacksonian Era created democracy for white men. At the national level, this was partly true. But presidential politics were not the center of early American political life. Using data painstakingly compiled by Philip Lampi, historians have discovered that somewhere between half and three-quarters of adult white males were eligible to vote before the Revolution; by 1812, almost the entire adult white male population could cast a ballot. Many of them, however, stayed home on election day. In the early 1800s, as organized political parties began to fight over issues like banking and infrastructure, that changed; turnout rose to 70 percent in local and state elections. Still, presidential polls remained dull and ill-attended. That changed in Jackson’s second run for the presidency in 1828. Heated debates and even-hotter tempers attracted men to the polls who previously only voted for governor or the legislature. Democracy for white men did not, however, spill over to democracy for everyone; in this same period several states rolled back laws that permitted free black men to vote.

For white men, the United States became a democracy by degrees, not by design, and it showed in the chaotic voting systems. While colonial Americans cast beans, peas, and corn into containers or called their vote aloud, in the 1800s most men either wrote the candidate’s name on a blank sheet of paper or turned in a ballot helpfully printed for them by the local political party or newspaper. Outside of Massachusetts, almost no one registered to vote. Even if someone challenged a man’s age or residency, there often was no way to prove it. Voting ran by routine, not regulation.

If not for rumors of nuns in distress, things might have kept bumbling along in this fashion. But in the 1830s, wild tales of forced conversions and sexual torture in nunneries inflamed Protestants already concerned about the trickle of Irish and German Catholics into the country. Between 1834 and 1836, a crowd ransacked and burned the Ursuline convent near Boston; inventor Samuel Morse — still memorialized in the telegraphic code — and prominent minister Lyman Beecher published anti-Catholic pamphlets; and the bestselling “Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk” popularized a fictionalized story of a Protestant Montreal girl forced into sexual slavery. In the anti-Catholic mood, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and New York passed registration laws between 1836 and 1840, although Pennsylvania’s and New York’s only applied to Philadelphia and New York City. But the nativist movement stalled; there simply weren’t enough foreign-born Catholics to sustain those fears.

Had potato tubers not begun to shrivel in the Irish soil in the summer of 1845, nativism might have remained stalled. But in that year, blight wiped out half of Ireland’s potato crop. Perhaps one million islanders — one-eighth of the population — died of starvation, and perhaps two million left, mostly for the United States, where they joined German Catholics fleeing their own food shortages. By the late 1850s immigrants outnumbered U.S.-born citizens in many large cities, and politicians fought over funding for parochial schools and control of church property.

In 1850, a nearly forgotten New York blowhard named Charles B. Allen had enough. To rally Protestants against immigrants, he founded a secret society officially called the Order of the Star Spangled Banner but better known as the Know Nothings. Two years later, Allen had only attracted 43 members, but, over the course of 1854, local political controversies swelled the group to one million, including former president Millard Fillmore. As the Whig Party collapsed in fights over slavery, the Know Nothings’ American Party elected about 100 congressmen, 9 governors, and a majority of the legislatures in several states (including Massachusetts). Four New England states banned state judges from naturalizing immigrants; Connecticut and Massachusetts passed literacy tests; Rhode Island required naturalized citizens to wait two years before voting; Maine forced immigrants to present naturalization papers three months before elections; New York, where the registration law had lapsed, re-enacted it for New York City.

Today, the ubiquity of voter registration blinds us to its impact. It is a price we all pay for voting and so no longer think of as a price at all. But nineteenth-century Americans understood the costs. Registering in person months before the election minimized the chance of fraud but doubled the difficulty of voting and the possibility of interference. “If the law of Massachusetts had been purposely framed with the object of keeping workingmen away from the polls it could hardly have accomplished that object more effectually than it does,” a labor organization later complained. For these reasons, and others, Alexander Keyssar’s excellent history of voting called the 1850s a period of “narrowing of voting rights and a mushrooming upper- and middle-class antagonism to universal suffrage.”

What saved voting, temporarily, was the Civil War. As the issue of slavery tore apart the Know Nothings, many Northern members slipped into the new Republican Party even though Abraham Lincoln and many party leaders repudiated nativist policies. Once the war came, hundreds of thousands of Irish and German immigrants enlisted in the U.S. Army. For a time this flood of foreign-born soldiers swept nativism away. In the years after the Civil War, 12 states explicitly enfranchised immigrant aliens who had declared their intention to become naturalized but had not yet been made citizens. Voting by non-citizens who planned to become naturalized was “widely practiced and not extraordinarily controversial” in this period, political scientist Ron Hayduk argues.

But the Civil War more dramatically transformed the political world of the nation’s four million slaves. By 1862, you could see the dawn of a new era at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, where slaveowners had launched their assault on the United States in April 1861. There, in May 1862, an enslaved wheelman named Robert Smalls gathered his family and other slaves onboard a steamer called the Planter. While the captain and white crew slept on shore, Smalls raised the Confederate Stars and Bars and sailed past the unsuspecting guard at Fort Sumter. Ten miles off the coast, Smalls turned the Planter over to a U.S. clipper ship. Soon he became a celebrity and, thanks to the prize the U.S. government paid him, modestly wealthy. Smalls used his fame to organize freedpeople to protest segregation and to demand their rights.

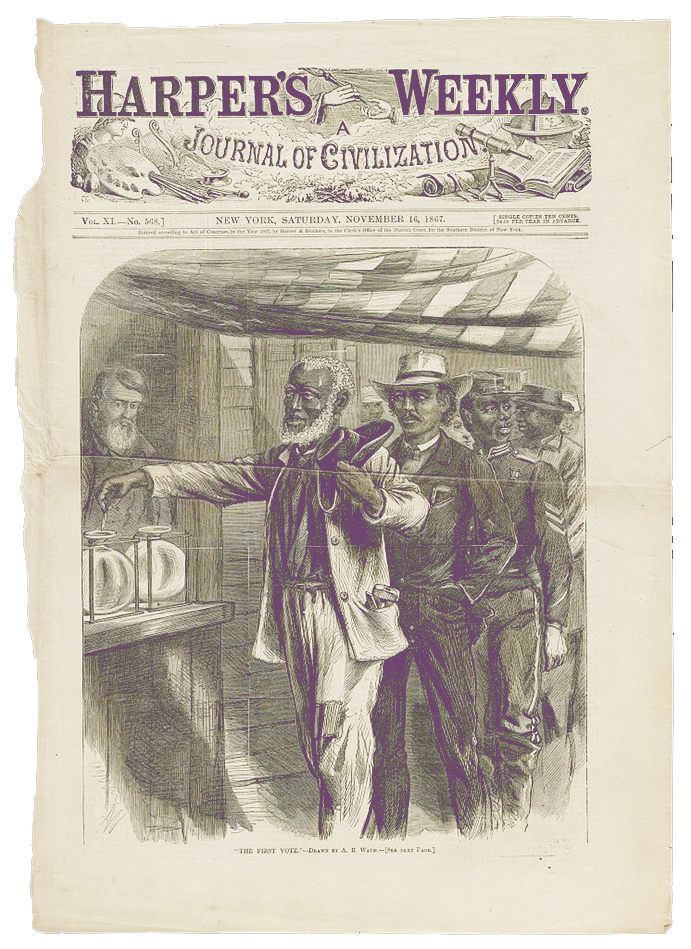

Smalls’ move into politics was part of a vast transformation of American politics. Prior to the Civil War, African-American men could only vote in six Northern states. But the flood of 200,000 black men into the U.S. Army and Navy inspired them — and others — to claim the vote as their due. “If we are called on to do military duty against the rebel armies in the field, why should we be denied the privilege of voting against rebel citizens at the ballot-box?” a delegation of Tennessee African Americans asked in January 1865. Although it took two years — and a winding political path — Congressional Republicans in the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867 enfranchised African-American men in 10 ex-Confederate states (all but Tennessee), put those states under military supervision, and dispatched generals to enroll black male voters and call elections for delegates to create new state constitutions.

In 1867, during what historian Julie Saville called “registration summer,” hundreds of veterans and activists like former 54th Massachusetts Infantry sergeant William M. Viney traveled “all through his District holding meetings.” Although freed women could not vote, they lobbied, cajoled, argued, brandished weapons, and even held sex strikes to convince kin and neighbors to register. “[R]egistration was their newly acquired badge of citizenship,” one government agent said. By the fall of 1867, more than 80 percent of eligible African-American men had registered. During the subsequent elections, at least 75 percent of black men turned out to vote in five Southern states. Democracy has a long history, but almost nothing to match this story.

Robert Smalls won a seat in South Carolina’s 1868 constitutional convention and then in the new state legislature. In conventions and subsequent state legislatures, Smalls and his compatriots tore down racial barriers; established public school systems, hospitals, orphanages, and asylums; revised tenancy laws; and tried (sometimes disastrously) to promote railroad construction to modernize the economy. Reconstruction governments also provided crucial votes to ratify the 14th Amendment, which is still the foundation of birthright citizenship, school desegregation, protection against state limits on speech or assembly, and the right to gay marriage.

Like every revolution, Reconstruction inspired a counter-revolution. One hundred eighty miles north of Robert Smalls’ hometown of Beaufort, South Carolina, the counter-revolution was brewing in the upcountry by summer 1868. Ku Klux Klans and other vigilantes there assassinated Benjamin Franklin Randolph, a wartime chaplain, constitutional convention member, and newly elected state senator, as well as three other African-American Republican leaders. Nevertheless black South Carolinians turned out in force, carried the 1868 election, and helped elect Ulysses S. Grant president. In Louisiana and Georgia, however, terrorists succeeded in scaring most African-American men from the polls.

In his March 4, 1869 inaugural, Grant called on states to settle the question of suffrage in a new 15th Amendment. Anti-slavery icon Frederick Douglass said the amendment’s meaning was plain. “We are placed upon an equal footing with all other men.” But the 15th Amendment did not actually resolve the question of who could vote or establish any actual right to vote. It merely prohibited states from excluding voters based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Its own language acknowledged that states could legitimately strip the vote away for other reasons. African-Americans and some Republicans had pressed for a broader amendment that would “protect everybody,” but proposed prohibitions on literacy, education, property, or religious tests died at the hands of northeastern and western Republicans who feared expanding the power of Irish and Chinese immigrants.

No one was more disappointed by the Fifteenth Amendment than Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She and other female suffragists hoped to “avail ourselves of the strong arm and the blue uniform of the black soldier to walk in by his side.” But abolitionist Wendell Phillips warned them that it was the “Negro’s hour,” and Republicans did not support them. Although women suffragists would soon prevail in Western territories, it would be fifty years before the Constitution protected women’s right to vote.

Nor did the 15th Amendment protect voters against terrorism. As Smalls and other African-American Republicans gained seats in Congress, they and their white allies tried to defend black voting through a series of enforcement acts that permitted the federal government to regulate registration and punish local officials for discrimination. But the Supreme Court soon undercut those laws. After a federal court indicted two white inspectors in Lexington, Kentucky for barring William Garner from voting in a city election, the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Reese overturned sections of the enforcement acts. In a sister case (U.S. v. Cruikshank) the court dismissed indictments against three white Louisianans for massacring dozens of African-Americans in a political coup in the town of Colfax. Without hope of victory, federal prosecutions for voting crimes fell by 90 percent after 1873.

[ Prime Essay by Gregory Downs: “19th Century Republicans Have A Lesson For 21st Century Democrats” ]

African-American Republicans fought back against terrorists by banding together for self-protection. Former slave William Heard knew the difference politics made; it was the Republican Party that opened the doors of the University of South Carolina to him and other black students for a brief window in the 1870s. In 1876, in the same county where vigilantes murdered Benjamin Randolph eight years earlier, Heard gathered black people on election eve. They “sang and prayed, drank coffee and ate sandwiches all night” then marched “at daylight” to “the polls and stood in line until we had voted five hundred Republican votes….Every man was armed with some kind of weapon.” Days later, when Heard tried to get affidavits attesting to the Republican victory, Democrats tied him up, carried him into the woods, and threatened to kill him.

Keeping African-American people away on election day was difficult, and potentially bad publicity, so white Democrats over the 1870s and 1880s passed registration laws and poll taxes, and shifted precinct locations to prevent black people from coming to the polls at all. In 1882, the South Carolina legislature required all voters to register again, making the registrar, as one African-American political leader said, “the emperor of suffrage.” Republican voting in the state dropped from 58,071 in 1880 to 13,740 in 1888. While Robert Smalls held onto his congressional seat, other black office holders disappeared. To disfranchise rural laborers, Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, North Carolina, and other Southern states doubled residency requirements.

Another way to bar African-American men was to expand the number of disfranchising crimes. Cuffie Washington, an African American man in Ocala, Florida, learned this when election officials turned him away in 1880 because he had been convicted of stealing three oranges. Other black men were barred for theft of a gold button, a hog, or six fish. “It was a pretty general thing to convict colored men in the precinct just before an election,” one of the alleged hog thieves said. In Richmond, Virginia, 2100 African-American men were disfranchised for felony convictions. According to historian Pippa Holloway, every Southern state except Texas added petty theft or other crimes associated with black men to the list of disfranchising felonies.

But the South was not the only region where disfranchisement was on the march in the 1870s and 1880s. The same Republicans who tried to protect black Southern voters from violence and fraud increasingly aimed to crack down on immigrant voting in the North, sometimes through those same federal enforcement acts. Northern cities had indeed changed dramatically. After immigration stalled in the late 1850s, nearly 25 million immigrants entered the United States between the Civil War and World War I, and many supported Democratic political machines like New York City’s Tammany Hall. “A New England village of the olden time . . . would have been safely and well-governed by the votes of every man in it,” historian Francis Parkman wrote in “The Failure of Universal Suffrage, “but now that the village has grown into a populous city [filled with] foreigners for the most part, to whom the public good is nothing . . . the case is completely changed.” In industrializing Providence, Rhode Island, property qualifications blocked 80 percent of adult men from voting in city elections. New Jersey Republicans imposed registration on the state’s cities in 1866 and 1870. California in 1878 purged registered voters in San Francisco until only 54 percent of adult males were on the rolls. Other states cracked down on paupers, even excluding impoverished Civil War veterans who lived in state-supported homes. Voting rights for permanent resident aliens were repealed in several states. Still, total voting in the North dropped only at the margins.

So it might have remained were it not for a bitter rivalry between two New York Democrats, reform-minded President Grover Cleveland and Tammany Hall-backed Governor David Hill. In 1888, Hill carried the governor’s election by almost 20,000 votes but his fellow Democrat Cleveland lost the state — and thus the presidency — by almost 15,000. The culprit, reformers decided, was not just Governor Hill but the ballot itself. Up to this election, voters still cast pre-printed ballots they received from party officials or precinct captains. In New York City, Hill’s backers had distributed tens of thousands of ballots that listed the Democrat Hill for governor and Republican Benjamin Harrison for president. Incensed reformers in both New York and Massachusetts went to work.

To solve the problem, reformers looked to the deep, deep South: Australia. In the 1850s, politicians there created the kinds of government-printed ballots we still use in many states. Voters received a pre-printed, official slate of names and generally put a check by the one they preferred. By the 1880s, this so-called “kangaroo voting” seemed the solution to every political problem. Reformer Henry George and Knights of Labor leaders hoped the Australian ballot would free workingmen from intimidation, while reformers in Boston and New York hoped it might eliminate fraud and make it difficult for illiterate men to fill out ballots. Massachusetts leapt first in 1889, and by the 1892 election a majority of states had passed the bill. In Massachusetts, turnout dropped from 54.57 to 40.69 percent; in Vermont from 69.11 to 53.02. One statistical survey estimated that voter turnout dropped by an average of 8.2 percent. The Australian ballot’s “tendency is to gradual disfranchisement,” the New York Sun complained.

At first it may be surprising that such a simple change could have such an impact. Checking the box next to a preferred candidate hardly seems like much of an obstacle. But by stripping political parties’ names from the ballot, the reform made it difficult for illiterate voters, still a sizable portion of the electorate in the late 19th century. But even more profoundly, the effort to eliminate “fraud” turned election day from a riotous festival to a snooze. Over time many people stayed home. In New York, voter participation fell from nearly 90 percent in the 1880s to 57 percent by 1920. “American ingenuity has done much with the primitive Australian form,” one journalist commented. The effort to save democracy from fraud had curtailed democracy.

The 1888 election was almost a very different turning point for voting rights. As Republicans gained control of the House, Senate, and White House for the first time in a decade, they tried to bolster their party by establishing federal control of congressional elections so they could protect African-American voting rights in the south (and, Democrats charged, block immigrant voting in northern cities). The bill’s dual purposes were embodied in its manager, anti-immigrant, pro-black suffrage Massachusetts Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge. Although the bill passed the House, it died in a Senate filibuster. Democrats swept the House in the fall 1890 elections and soon repealed many of the remaining voting rights provisions.

Those Lodge Bill debates failed to change the national law, but they did convince Mississippi Senator James George that his state should eliminate African-American voters before the federal government stepped in. George orchestrated a state constitutional convention that dramatically lengthened residency requirements, imposed a $2 poll tax, added a literacy test, expanded felonies that disfranchised voters, and added the Australian ballot. “It will never come to pass that the neck of the white man shall be under the foot of the negro, or the Mongolian, or of any created being,” George promised the U.S. Senate. African-American registration in Mississippi soon fell from 190,000 to 9,000; overall voter participation dropped from 70 percent in the 1870s to 50 percent in the 1880s to 15 percent by the early 1900s. Soon almost every other Southern state followed suit. The Australian ballot law “neutralized to a great extent the curse of the Fifteenth Amendment, the blackest crime of the nineteenth century,” an Arkansas official bragged. When states rewrote or amended their constitutions, they — like Alabama — looked to Massachusetts as a guide to restricting votes. “We have disfranchised the African in the past by doubtful methods,” Alabama’s convention chairman said in 1901, “but in the future we’ll disfranchise them by law.” In South Carolina Robert Smalls, one of a handful of black men in the new constitutional convention, pleaded with delegates not to undo his work at the 1868 enfranchising convention, but his arguments fell on deaf ears.

These laws and constitutional provisions devastated voting in the South. When Tennessee passed a secret ballot law in 1889, turnout fell immediately from 78 percent to 50 percent; Virginia’s overall turnout dropped by 50 percent. For African-American voters, of course, the impact was even more staggering. In Louisiana black registration fell from 130,000 to 1,342. By 1910 only four percent of black Georgia men were registered. White planters used their newfound power to create a system of Jim Crow peonage. “If they couldn’t slave the nigger back like he used to be, [disfranchisement] was pointin the nigger in that direction,” Alabama tenant farmer Ned Cobb said. Poll taxes, intimidation, fraud, and grandfather clauses all played their part, but the enduring tools of registration and the Australian ballot worked their grim magic, too, and made voters disappear.

Jim Crow stripped away Jackson Giles’ vote and that system lasted long enough to shape the world of current U.S. Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III. In Spring 1965, when Sessions was a senior in high school, two-thirds of the residents of his home county in Alabama were black, and none of them could vote. The Civil Rights Movement’s successful lobbying for the Voting Rights Act changed the South quickly and dramatically. Here’s one piece of evidence: Sessions has openly defended the Confederate flag and ultra-segregationist George Wallace, but he has apparently never spoken publicly in favor of the men who disfranchised Jackson Giles and tens of thousands of other Alabamans.

Four months before Jackson Giles tried to register to vote, a white Columbia University graduate student named Walter Fleming wrote to Alabama’s governor, asking for evidence that the constitution was race neutral. Fleming, a native Alabaman, was puzzled that his New York Republican friends “seem to think” that the new state constitution disfranchised “at once and forever all negroes, whether educated, or property-holders, or not.” Alabama was not being racist, in his view; it was simply applying laws already tried in New York and Massachusetts. Fleming’s apologies for Alabama did not end in graduate school. Over an impressive scholarly career, Walter Fleming would denounce “Africanization in government” during Reconstruction and praise the Ku Klux Klan for trying “to regulate the conduct of the blacks” to protect “honor, life, and property.” Fleming’s accounts helped shape high school and college instructions for decades, and his name persists in a prestigious lecture series given at Louisiana State University each year. He has been dead for more than 85 years, but the question he asked Alabama’s governor still persists.

Was the story of Alabama — of the South — the story of the United States? Which is another way of asking this: Was the United States a democratic nation? In the landmark case Shelby County v. Holder, Chief Justice John Roberts turned the disfranchisement of the 1890s into a racial and regional exception, one that had since been overwhelmed by the national tide of democracy. “Our country has changed,” Roberts wrote in the majority opinion. This is part of what political scientist Alexander Keyssar critically called the “progressive presumption” that there is an “inexorable march toward universal suffrage” interrupted only by anomalous, even un-American, regional and racial detours. Is it better to think that the United States is democratic when it isn’t distracted by racism? Or to think that the United States might not be democratic at all?

But the tools that disfranchised Jackson Giles were not all Southern and not only directed at African-American men. When the United States conquered Puerto Rico and the Philippines, it imposed the Australian ballot there, too. Registration, Australian ballots, and precinct placement still form the basis of our political system.

Like many contemporary Democrats, Jackson Giles looked to the courts to save him. But in 1903, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, a Massachusetts native, denied Giles’ appeal on the grounds that the court could not intervene in political questions. If citizens like Giles suffered a “great political wrong,” Holmes intoned, they could only look for help from the same political system that had just disfranchised them. The great writer Charles Chesnutt wrote that “In spite of the Fifteenth Amendment, colored men in the United States have no political rights which the States are bound to respect.” It was a “second Dred Scott decision,” white and black activists lamented.

When word came down about the Supreme Court decision in spring 1903, the Alabama River had already crested in Montgomery. By the time Giles and his fellow activists called a mass protest, the annual floods had receded. Giles too would soon recede into the darkness of history; scholars still struggle to discover when and where he died. But at this moment, he represented perhaps the last, best hope to save democracy in the United States. As he called the activists’ meeting into session, he began to hum a “plaintive rendition” of “One More River to Cross.” Like all spirituals, this song survives in several versions, but many begin the same way: “O Jordan bank was a great old bank!/There ain’t but one more river to cross.”

In the voting rights struggles of the current moment, detailed in the upcoming essays in this series, we might ask whether we have yet safely crossed that river to the safe shore of democracy. History can tell us how the tools we use today have been used in the past, but it cannot answer these questions: When the floods of disfranchisement reach the danger line, will we make it safely to the other side? Will we flail to keep our head above water? Or will we drown?

[ Read Gregory Downs’ list of sources and recommended reading ]

Gregory Downs is a Professor of History at University of California, Davis, and the author of two books on Reconstruction, including After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War. He is currently completing a book on the Civil War as the second American revolution. He is also the author of a book of short stories and co-author (with Kate Masur) of the National Park Service’s first-ever Theme Study on Reconstruction.

Made possible by