Houston photographer Lynn Lane has voted in every general election and primary over the last five years. He hasn’t changed his address, so he was stunned this year to receive an official letter warning him that he might soon be erased from the rolls.

Lane was one of 4,000 voters whose registrations were personally challenged by a single Republican, Alan Vera, who chairs the Harris County GOP’s “Ballot Security Committee.” This sort of individual challenge is illegal in some states, but Texas law permits it. Republicans blamed the county’s election registrar, a Democrat, for automatically suspending the registrations of 1,700 of those voters — but not before Vera boasted on his Facebook page about what he was up to: Voters whose registrations were suspended for failure to return a confirmation postcard would have to cast provisional ballots, which are “reviewed by the Ballot board,” he wrote, “and I appoint all Republican members of that board.” His “project,” he added, “could make a big difference in the November election results.”

Stories like Lane’s are becoming all too familiar to a growing number of American voters, who are being dropped from the rolls at a rapid clip, particularly in states with histories of voter discrimination. Such purges are the new face of voter suppression, civil rights advocates say. Unlike the Jim Crow laws of yore, which blocked access to the rolls with tests and taxes, voter purges take registered voters — often, voters of color — and make them disappear. And unlike voter ID laws, which at least give voters advanced warning, purges can be sudden, silent, untraceable, and irremediable.

“The big challenge with purges is that they tend to happen in somebody’s office outside of sunlight, with somebody stroking a few keys on the keyboard,” says Myrna Pérez, deputy director of democracy program at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice. “And that makes it really hard to know that anyone has been impacted until they go to the polls. And by that point, it is often too late.”

Everyone agrees that election officials should regularly scrub their rolls of voters who have died, moved elsewhere, or have lost the right to vote to a felony conviction. But purges have a long history of being used to suppress the vote. Even the practice of keeping voter lists originates with post-Civil War efforts to reduce registration among African Americans in the South and immigrants flocking to industrial urban centers. And while death, relocation or felony conviction rates are not dramatically increasing these days, voter purges are way up.

Some 16 million voters were swept off the rolls between 2014 and 2016, compared with 12.3 million between 2006 and 2008 — an increase of almost four million, according to a July Brennan Center report. Still more voters have been purged since the 2016 election, the center found. That includes 648,598 erased in North Carolina — a full 11.7 percent of the state’s total voter roll. Florida dropped 981,569 voters from its rolls, or seven percent, in that same window. Georgia has deregistered 10.6 percent of its voters since 2016, or 692,707 — more than 500,000 of them were wiped out in a single day. The precise number of eligible voters caught up in such purges is impossible to estimate, given that mass voter removals tend to go unannounced and leave no trace. But it’s fair to say that in next week’s midterm elections, tens or even hundreds of thousands of voters who believe that they are registered may turn up to the polls only to discover their names are not on the list.

Voter list controversies and lawsuits over purges abound, many in states with tight, closely watched gubernatorial contests such as Florida, Georgia, and Ohio. Nineteen states have tossup congressional races on the ballot this November that will decide control of the House, raising the stakes still further. And plenty of red flags signal voter list trouble ahead:

- Indiana’s GOP legislature last year cleared the immediate purging of voters flagged by the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program, which purports to identify voters who have moved, but which is best known for its astronomical error rate. A court blocked the removals, following two separate lawsuits from voting rights advocates who said the instant purges violated federal laws that require voters to receive advance notice. Those filing suit say 600,000 voters were run through the “Crosscheck” system, though it’s not known how many were purged as a result. By one estimate, the state has erased 481,235 voters since 2016, and voting rights advocates fear many will not learn they are no longer on the rolls until they turn up on Election Day.

- After Alabama moved 340,162 voters to an “inactive” list last year because they failed to return a postcard to the state, chaos marred the December special Senate election, which Democrat Doug Jones won by some 20,000 votes. Among those erroneously deregistered was Republican Congressman Mo Brooks, who had run in the GOP Senate primary without success. Voters listed as “inactive” had a legal right to cast regular ballots, say civil rights advocates who were monitoring the polls, but dozens were improperly handed provisional ballots, which often go uncounted. At least one eligible voter was told he could not vote at all.

- In Georgia, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and its allies this month sued Secretary of State Brian Kemp after the Associated Press reported in early October that the state had put 53,000 voter registrations on hold under the state’s exact match” system, 70 percent of them African American. The state’s system, which the Lawyers’ Committee describes as “no match, no vote,” suspends applications if even a typo or missing hyphen creates a mismatch with public records. Ted Enamorado, a Princeton University PhD candidate, has run the numbers and found that nonwhite voters are “especially likely to be harmed.” A subsequent tally showed that fully 75,000 applications were “pending,” though Kemp’s office said about 28,000 were duplicates or clearly ineligible. But that still leaves 46,946, by Georgia Public Broadcasting’s estimate, who may run into a problem on Election Day if their IDs don’t “substantially match” what’s on their voter registration, or who may be forced to cast provisional ballots. And those who don’t resolve the match issue within 26 months — meaning those who don’t vote this year, and don’t otherwise clear up the mismatch with the state — will be removed from the rolls. And even as Kemp oversees the election, he is running in it as the GOP gubernatorial nominee against a Democrat who could become the state’s first African American woman governor.

Could eligible voters kicked off the rolls exceed the margin of victory in close contests? It’s possible. In Indiana, polls show Senator Joe Donnelly leading his opponent, Republican Mike Braun, by as little as one point, which means the election could be decided by several thousand votes.

Purges invariably hit voters of color, students, and low-income voters hardest, for a variety of reasons. Such voters tend to move often, and are less likely to reliably receive or respond to mass mailings requesting verification. Immigrant and African American voters also share many common last names, making them more likely to turn up as double-registered in “Crosscheck.” The upshot is that the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, which includes laws for maintaining voter rolls and was enacted in part to protect voters against discriminatory purges, has been turned on its head to target vulnerable voters instead.

“These purges have been and continue to be racially disparate in their effect,” says Catherine E. Lhamon, who chairs the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The commission, a nonpartisan government agency, released a report last month that identified voter purges as a leading challenge to minority voting access in the U.S. today.

Most election officials tidy up their voter lists with the best of intentions. But many purges go awry, sometimes with disastrous results. From the notorious Florida purge of some 12,000 eligible voters in the 2000 presidential election (ultimately decided by 537 votes), to the 39,000 voters removed from the Virginia rolls based on a faulty database of supposed felons in 2013, the numbers are staggering.

Eligible voters have been deregistered or inactivated in more than a dozen states, from Arkansas to Kansas and North Carolina, according to the Brennan Center, which blames rising purges on multiple factors. These include the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder ruling in 2013. That ruling reversed a Voting Rights Act mandate that had required states and regions with a history of voter discrimination to win Justice Department approval before changing their election rules.

States now freed from “preclearance,” including Georgia, Texas, and Virginia, have been wiping voters from the rolls at a much higher rate than other states, the Brennan Center found. Georgia alone removed 1.5 million voters from its lists between 2012 and 2016 — twice as many as it had between 2008 and 2012, prior to the Shelby ruling.

The Brennan Center also blames “election fraud vigilantes,” who are now filing more purge-related lawsuits than civil rights advocates, and for whom purges have overtaken voter ID laws as the weapon of choice. These include the Public Interest Legal Foundation, led by “election integrity” crusader J. Christian Adams, an allied conservative group confusingly dubbed the American Civil Rights Union, the conservative legal outfit Judicial Watch, and True the Vote, which trains regular citizens to challenge voters personally.

Such groups have been raising the alarm about widespread voter fraud in the U.S. for years, despite a pile of evidence that in-person voter impersonation is virtually non-existent. Now they’ve vaulted to the national stage, thanks to the election of President Donald Trump, who urged his supporters as a candidate to monitor polling places in “certain areas,” and claimed with zero evidence once elected that three to five million illegal votes had cost him the popular vote.

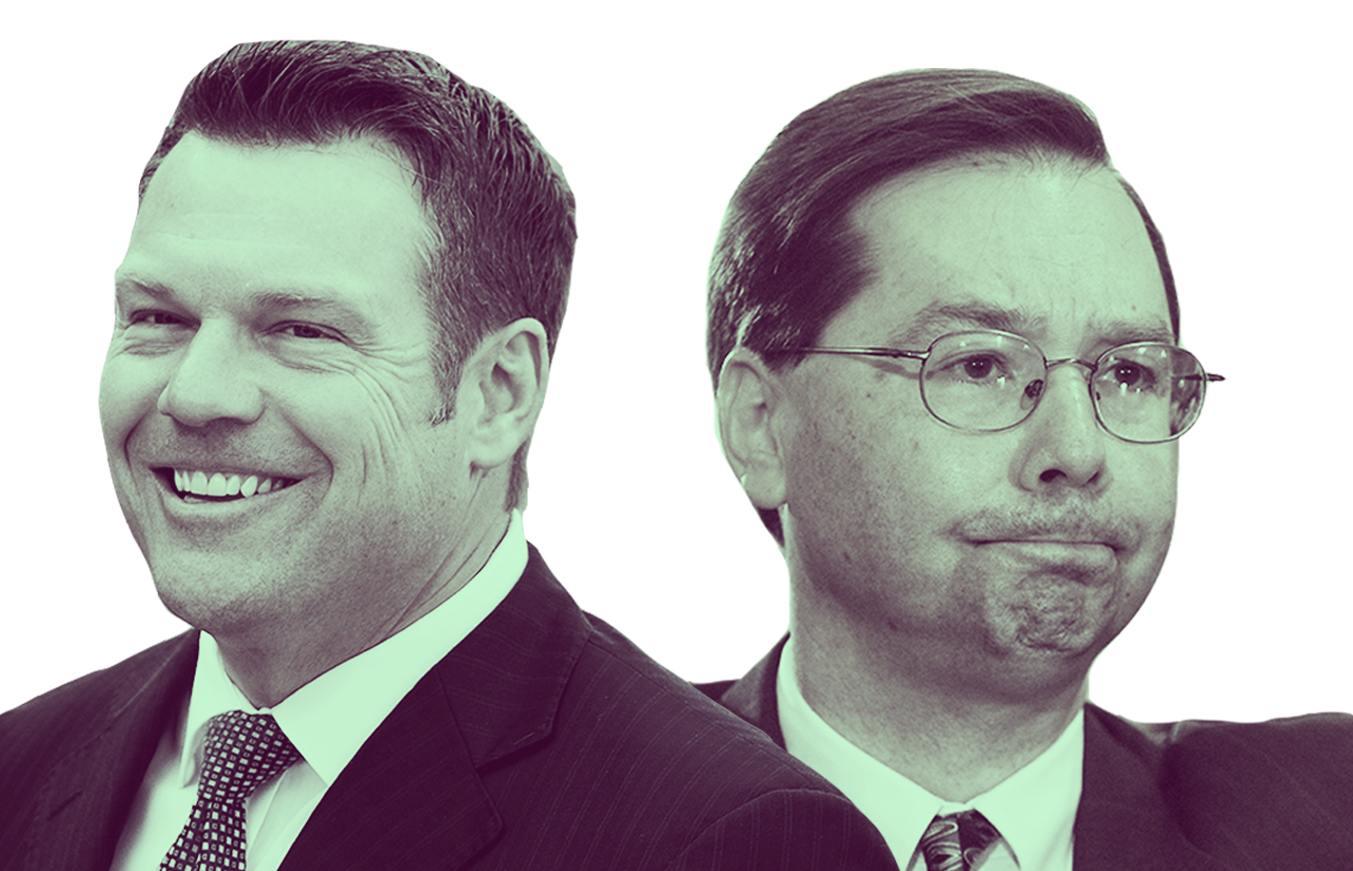

Under Trump, the Justice Department switched from defending voters against blanket purges to demanding that states hand over evidence of how they are deregistering ineligible voters, a possible precursor to sanctions. Trump installed a cast of voter fraud alarmists, including Adams, conservative scholar Hans von Spakovsky, and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, who advocates proof of citizenship for registration, on his so-called Advisory Commission on Election Integrity. That panel placed “cleansing” the rolls at the top of its agenda before collapsing amid lawsuits and disarray.

A Trump-appointed U.S. Attorney has now picked up where that commission left off, demanding millions of voter records from election officials North Carolina, who have fended off the request for now. The Justice Department abruptly reversed itself in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, a Supreme Court case over Ohio’s purge practices: Having previously opposed them during the Obama administration, the DOJ now defended them. Trump also won confirmation to the Supreme Court of an overtly partisan justice in Brett Kavanaugh, who has refused to say whether he believes widespread voter fraud exists.

The Husted case was fraud-obsessed “integrity” watchdogs’ biggest coup so far this year. The June 11 ruling upheld Ohio’s controversial voter purge methods, which removed 200,000 voters from the rolls in 2015 alone.

Ohio initiates the voter purge process for any voter who has skipped a single election. A voter who does not show up at the polls over a six-year period, and does not respond to postcards requesting verification from the Secretary of State, is removed from the rolls. The massive purges removed African American voters in the state’s five largest counties at twice the rate of whites.

The decision triggered hand-wringing on the left, and jubilation on the right, and no anti-fraud group had more reason to celebrate than Judicial Watch, whose 2012 lawsuit challenging the accuracy of Ohio’s voter rolls had forced the state to adopt its aggressive purge practices to begin with. The Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute was “a big institutional win for Judicial Watch,” crowed its president, Tom Fitton, and “should send a signal to other states” to follow suit.

There’s nothing innately wrong with removing voters from the rolls, of course. The National Voter Registration Act of 1993 set out both to expand voter registration and enhance election security. The law was a balancing act, requiring states to offer registration at motor vehicle departments and other public agencies (hence the moniker “Motor Voter” law), but also to make “a reasonable effort” to cull ineligible voters.

And there are plenty of improperly registered voters. A 2012 report by the Pew Center on the States — widely cited by fraud-fearing conservatives — uncovered some 1.8 million deceased voters on the rolls, about 2.75 million people registered in more than one state, and 24 million registrations that were “no longer valid or significantly inaccurate.”

Even the label “voter purge” is “a loaded term in many ways,” says David Becker, executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and research. Election administrators prefer the term “list maintenance,” which they say allows them to run elections more smoothly and cost-efficiently, avoiding long lines and better predicting turnout. Election officials “just want accurate data,” says Becker. “They know there are people on their lists who shouldn’t be on, and they want to get them off.”

Nor is the fight over registration rolls all about delisting voters. Voter erasures are taking place amid a countervailing movement to add voters to the list. Even as Georgia flagged tens of thousands of voters as ineligible, the state added more than half a million voters to the rolls between 2016 and 2018, thanks to an automatic voter registration system put in place under GOP Governor Nathan Deal that has boosted active voters by 15 percent, including substantial upticks among voters of color. The system automatically registers people seeking or renewing driver’s licenses unless they opt out, a process election officials say improves accuracy and makes verification failures less likely.

Georgia is now one of 13 states, along with the District of Columbia, with automatic voter registration. Also taking off is same-day voter registration, the ultimate backstop for voters who discover they are off the lists on Election Day. Same-day voter registration has grown from only six states in 2000 to 17 plus D.C. today, and takes effect in an eighteenth, Washington State, next year.

If purges are up, so are new registrants — this year, a record 800,000 new voters signed up on National Voter Registration Day, twice what organizers had anticipated. And Kobach’s Crosscheck system is now on hold, following the disclosure of numerous security weaknesses, and the withdrawal of more than half a dozen states. In the meantime, states are flocking to use ERIC, a bipartisan Electronic Registration Information Center that allows states to check voter information against numerous government databases. In contrast to Crosscheck, which principally compares voters’ names and dates of birth (shared by thousands of voters) ERIC draws on broader data sources such as Postal Service and driver records, resulting in fewer errors. States also use ERIC not just to prune lists, but to identify voters who should be registered and help get them on the rolls.

Even the Supreme Court’s Husted ruling had a silver lining, say civil rights advocates: The majority opinion by Justice Samuel Alito upheld Ohio’s purge practices, but also reaffirmed a crucial pillar of the voter registration laws: That voters must receive notice before being delisted. This affirms that instant purges such as the one Indiana tried last year for voters flagged by “Crosscheck,” for example, are patently illegal.

Some purges are more about ineptitude than partisan or racial targeting. One of the worst botched purges in recent memory was in New York City, which admitted last year as part of a settlement agreement that election officials had “knowingly and illegally” purged more than 200,000 voters from the rolls, most of them Brooklyn dwellers, before New York’s 2016 presidential primary. The state sent notices to voters who had not voted since 2008, but failed to wait two federal elections, as required under the NVRA, before erasing them. The purge hit voters in Hispanic majority election districts the hardest, but was nevertheless attributed to administrative mismanagement, not animus.

For all that, many purges today are taking place without proper safeguards, based on bad data, and at the behest of deep-pocketed conservative groups whose voter fraud warnings are not grounded in fact.

Voter list maintenance is like surgery, says law professor Justin Levitt — precision is the key. “When your surgeon knows what they’re doing it can be life-saving,” says Levitt, who served in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Barack Obama. “But when my neighbor offers to operate on me with a chainsaw on a rickety table in the yard next door, that is not medical care I am inclined to pursue.”

Increasingly, that chain saw has been wielded by the likes of Adams, Kobach, True the Vote President Catherine Engelbrecht, and a growing citizen brigade. Their war on supposed voter fraud deploys a two-part strategy to “cleanse” the rolls. One: bully election administrators through threatening letters and lawsuits that allege their voter records are error-riddled and violate the NVRA’s requirement to make “reasonable efforts” to keep lists up to date. Two: train average citizens to challenge their fellow voters, both at the polls and in local election offices.

Key to their efforts are private voter challenges, which are permitted in 39 states, and which require supporting documentation in only 15 of those states. The NVRA also allows “civil enforcement and private right of action,” clearing the way for private lawsuits. In the past, purge-related suits were mostly brought by civil rights advocates alleging that voters were erased in violation of the NVRA’s requirement that removals be “uniform, nondiscriminatory,” and in compliance with the NVRA, which also bans purges in the 90-day window before an election. But lately, the bulk of purge-related suits challenge election officials for failing to maintain accurate lists.

As early as 2010, Adams boasted that, thanks to the NVRA’s private right of action, “I have given sixteen states the legal notice required to alert them that they have violated Section 8 of Motor Voter. I am working with private citizens across the nation to help ensure that the elections in November aren’t plagued by ineligible voters.” Last year the group sent 248 letters to county election officials, threatening that if they didn’t cull their rolls of voters who had died or moved away, they would face legal action.

“If you make a high-profile example out of one county, then others have a very good chance of following it,” explains PILF spokesman Logan Churchwell. Typically, the letters alert county officials that they have more registered voters on their rolls than citizens, based on Census records.

But those claims of inflated voter rolls are often exaggerated or flat-out wrong, concludes a recent Brennan Center report that examined the activities of four groups leading the voter purge charge: The American Civil Rights Union, the Public Interest Legal Foundation, Judicial Watch and True the Vote. Together, those groups have sent letters to 450 jurisdictions since 2012 urging more aggressive purges.

In three counties in California and Texas, for example, PILF maintained that registered voters outnumbered eligible voters. But the Brennan Center, in a data analysis with two allied groups, found that the opposite was true. PILF also had a tendency to count “inactive” voters as “registered,” the report found. The conservative groups were also more likely to file suit in regions where African American and Latino voters predominate.

When the American Civil Rights Union demanded a few years back that the heavily African American county of Noxubee, Mississippi, send postcards to verify the eligibility of all 9,000 of its voters, election official Willie Miller balked.

“It was going to disenfranchise my voters,” says Miller, observing that most such cards end up gathering dust on a bureau, and that the ACRU was demanding that the cards be labeled “non-forwardable,” meaning they would not reach voters who moved at their new address. The county eventually reached a settlement agreement with the help of a pro bono lawyer that involved a less onerous review of voter records.

“I felt that they were picking on us because we were a majority black county, and we did not have the finances to protect ourselves by getting a lawyer,” says Miller, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher. “And this was just going to be an easy rollover, and they were going to go on to bigger places.”

Such lawsuits from the right have yielded mixed results, in part because voting rights advocates like the ACLU, Common Cause, Demos, the Lawyers’ Committee, the League of Women Voters and the NAACP have successfully fought back in court. Private groups defending voters have filed more suits to protect voters than the Justice Department itself in recent years.

But voter purges led by local grassroots activists are harder to police, as when volunteers with a North Carolina outfit called the Voter Integrity Project started carrying boxes full of thousands of voter challenge forms into state election offices in 2016. The man behind the challenges was retired Air Force veteran Jay DeLancey, who founded the Voter Integrity Project on the model of True the Vote. DeLancey maintained that his group “followed North Carolina law scrupulously” in filing 6,000 voter challenges in Moore and Cumberland counties, based on a mass, private postcard mailing.

But the North Carolina branch of the NAACP successfully sued, arguing that the state’s purge of 3,500 to 4,000 voters in 2016, which partially resulted from the Voter Integrity Project’s efforts, violated the NVRA because it took place within 90 days of the election. A judge said the county’s process for removing challenged voters was “insane,” and sounded like “something that was put together in 1901.”

In Virginia, PILF and Adams face a defamation and voter intimidation lawsuit by the League of United Latin American Citizens of Richmond and allied groups, following the release of two “bombshell” reports distributed in Virginia that purported to list the names of more than 1,000 “illegal registrants” who turned out to be eligible voters. Sporting sensational illustrations of flying saucers on their covers, the “Alien Invasion” reports listed voters by name and in many cases included their personal identifying information.

One of the voters named in the suit, an African American woman named Luciania Freeman, first registered to vote when she was 18 but “will not re-register to vote until the court tells PILF to stop what they’re doing, because she’s scared,” says Allison Riggs, senior attorney in the voting rights section of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which joined in the suit. Another voter, Eliud Bonilla, had considered running for office one day, but now fears that being wrongly accused as a felon and non-citizen will subject him to “birther” conspiracies, the suit states.

“This is what modern-day voter intimidation looks like,” says Riggs.

“Those are not our lists of names,” responds Churchwell, of PILF, when asked about the defamation suit. “Those are state names.” What critics “are glossing over,” he argues,

“is that these are people that the State of Virginia kicked off the voter rolls, and called them noncitizens while doing it. So the messenger is getting shot here.”

On July 20 of last year, Georgia graduate student Jennifer Hill received a letter from the Chatham County Board of Registrars. It read: “You are hereby notified that the City of Thunderbolt has challenged your right to vote in their municipal election on November 7, 2017.” The letter instructed her to contact the City of Thunderbolt and summoned her to an August 30 public hearing, stating: “Before your name may be removed from the list of registered voters, a hearing must be held to determine that you are no longer qualified.”

Reading the letter aloud from her front porch on a Facebook Live video, Hill interrupted herself at one point to declare: “Wow. I am so angry.” The comments started rolling in. Read one: “Contact the ACLU now.” As it happened, the ACLU contacted Hill, ultimately restoring her and 300 other eligible voters to the rolls in Thunderbolt and nearby Tybee, after it was determined that election officials had flagged them for removal simply because their names had failed to turn up on the county’s water bills.

I'm reposting this because I was just TODAY interviewed for this story AGAIN! It's not going away. Georgia has issues that need addressing for the voters. RESIST AND SHARE. If I can get a letter like this, you can. FYI, with the help of Sean Young of the ACLU Georgia I won my suit against the state and the attorney general had to rewrite the rules for challenging a voters standing to vote. I was so surprised I HAD to live post this! THIS is how they actively set about disenfranchising and taking your right to vote!

Posted by Jennifer Hill on Thursday, July 20, 2017

But for Hill, the incident still stings. “I couldn’t get more American if I tried,” says Hill, 46, who is an Army veteran and former police officer. “I’ve still never received an official explanation.”

Voter frustration and disillusionment are among the insidious side effects of voter purges, say civil rights activists. Overzealous purges are part of a broader voter suppression strategy, says Stuart Naifeh, senior counsel at Demos.

“First, you make it harder for people to vote by imposing ID requirements, or proof of citizenship requirements,” says Naifeh. “And then when they don’t vote because you have been successful in keeping them away from the polls, you purge them for not voting.”

The problem is compounded when election officials combine purges with stern-sounding letters, calls to hearings, and even visits from police. Three years ago, the majority-white board of elections for Hancock County, Georgia, challenged the eligibility of 17 percent of the voters in the town of Sparta, virtually all of them African Americans, amid a hotly-contested local election that pitted black versus white candidates.

“The sheriff’s office was deployed to the homes of targeted voters who were issued summonses requiring that they come down to the local office to provide proof of their right to vote,” according to one account. A settlement agreement following a lawsuit by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law restored those voters to the rolls.

“They claim they are promoting election integrity,” says Naifeh of groups like PILF, “but when you kick people off the rolls who are legitimate, or when you are targeting particular communities, the result is people feel like the elections are stacked against them, which reduces turnout.”

The resulting confusion and wait times for those standing in long lines behind voters haggling with election officials also hurt voter confidence.

“There are people who have every intention to vote, plan to vote, get to a polling place and then are not able to vote,” says Lhamon, of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “It can be embarrassing. It discourages active participation in democracy in the future.”

On Election Day, by far the most common problem that voters report when they call in to the national Election Protection Coalition, say civil rights advocates, is some version of an increasingly familiar complaint: “I thought I was registered to vote, but I’m not on the list.” This year, civil rights groups are both battling voter purges and registration suspensions in court, and urging voters repeatedly to check their registration status.

In some states, such as Ohio, voting rights advocates have actually tried to track down eligible voters who have been or may be purged, and help them get back on the rolls. It’s a tall order, given that the state has 88 boards of election, says Mike Brickner, Ohio state director for All Voting is Local, a voting rights campaign spearheaded by the Leadership Conference Education Fund.

Brickner and his team have been combing voter data to identify voters who missed an election and were mailed a postcard by the state asking them to confirm their eligibility — the first step in removing voters from the rolls. Some 500,000 Ohioans fall into that category, says Brickner, and his groups has been texting each one to urge them to check and update their registrations. It’s laborious work, Brickner acknowledges, but he notes that an eligible voter turned away once may lose confidence in the system, and never vote again: “It’s incredibly damaging.”

Eliza Newlin Carney writes the Democracy Rules column for The American Prospect.

Made possible by