This morning I was reading this Slate article by Rick Hasen and Dahlia Lithwick on newly released papers which seem to show the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist held on to his segregationist views well into his time as chief justice. (For background, as a SCOTUS clerk in 1952, Rehnquist wrote a memo explicitly defending the constitutionality of Plessy v Ferguson and the segregationist system that was built up on it. He later played a key role in organized voter suppression efforts in Arizona in the 1960s.) Hasen and Lithwick tie Rehnquist to the current Court majority’s view that the 14th Amendment is essentially a warrant for color blindness in the law.

The 14th Amendment particularly has implications which were very much by design that go beyond the fate of post-war ex-slaves. It essentially creates a thing we now take for granted, the status of citizen of the United States. It also has implications beyond things the architects of the amendment could have conceived of. But there are certainly concrete things that are totally clear about it and the other Civil War amendments if you spend even some basic time understanding why they were created, what they mean and what they meant to accomplish. Reading Hasen’s and Lithwick’s piece was helpful, reminding me of this by showing the bust-up collision between the actual Civil War amendments and the theoretical latticework that gets promoted in Federalist Society world and in some ways (albeit often in a much more benign form) in law schools generally. In the latter case, there’s nothing wrong with theory. It has its place. It’s necessary if your aim is not simply historical understanding of the amendments but some level of application to present-day realities.

But the collision with the historical reality tells you that the “color blindness” theory isn’t simply wrong — it’s nearly absurd if you try to reconcile it with that past.

The Civil War was fought fundamentally over slavery and the various roots it put down into American society, economy and culture generally. The result of the war was to abolish slavery, though that’s not the same as saying it was originally fought with that aim in mind. The Civil War amendments were placed in the Constitution first to make the settlement permanent and unchangeable. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was righteous but at least open to question in constitutional terms. So it had to be made permanent, embedded in the Constitution itself. To another degree, the amendments were to make good on all the blood that had been shed. When you have more than half a million people dead you don’t want to settle for half measures. You need to make it really mean something.

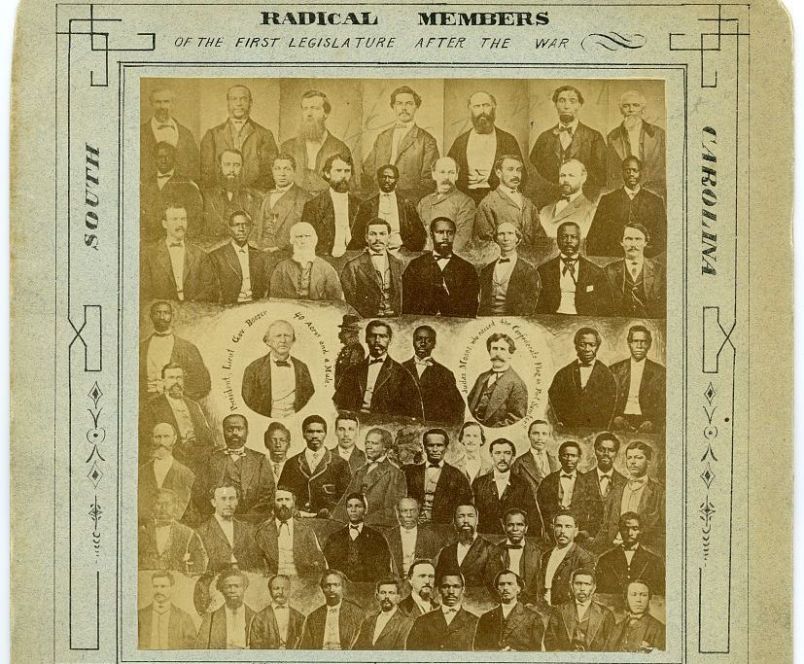

But over the course of the late Civil War and first attempts at Reconstruction, there is a growing recognition that it’s not enough to abolish slavery. If you don’t provide the freed slaves with the full citizenship package they will inevitably fall back into or rather be pushed back into if not slavery than its functional equivalent. This is precisely what Southern white political leaders were doing in 1865 and 1866, creating a new system of de facto slavery. What is key to understand is that this is not simply about principle and rights. There is a strong political and politico-economic reasoning. Republicans (and to some extent pro-Union Democrats, many of whom were later folded into the GOP) realized that they needed the ex-slaves to have political power. That was the only way to prevent what was formerly the “slave power” from reasserting itself.

The point here is not to portray these moves in narrowly political or cynical terms. It’s that the “political” and the constitutional are in constant interaction, now and always but especially in these critical years. It is also only fair and accurate to note that especially in the decade after the Civil War Republicans believed – often with good reason – that the electoral interests of the Republican party were synonymous with those of the country itself and the post-Civil War settlement, that the Democratic party was functionally the post-war embodiment of the Confederacy. In the later years of the 19th century this often become a self-serving Republican conceit but in these early years it was genuinely believed and often reflected reality.

In any case, the political self-interest tells an important story. If you understand the period and intentions it is specifically that the country has to build up the African-American population of the South so that it can stand on its own feet in terms of political power, which requires both economic and social power. Otherwise the whole situation is going to slide back into something like the old pre-Civil War days and the reemergence of the “Slave Power.” That wasn’t only about the loss of rights and freedom for the former slaves but the reemergence of slave power that endangered American freedom generally. Some of these ideas can seem like they’re out of another world. And in a way they are: the past is a different world. But you have to get inside these ways of thinking to understand the period.

This is obviously a complicated topic which I can’t do justice to in a single post. We also know that in fact starting in the 1880s and 1890s, the South did slide back into system of thorough political and economic subordination, if not outright servitude. Without federal troops and a consistent political commitment in the North, the formal protections of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments simply weren’t enough. They weren’t self-enforcing. But of course none of these failures are relevant in terms of what those amendments were meant to achieve, how their authors understood them or what the plain text says.

As I’m sure some wise person once said, constitutioning is hard. Just what these amendments require or make possible today is complicated. But the big picture is not. Any idea that these amendments are about color-blindness before the law doesn’t remotely square with reality.