International Workers’ Day, or May Day, comes on the heels of one of the worst periods for workers in quite some time. In the last six weeks, more than 30 million Americans filed for unemployment. At the same time, the S&P 500 gained more than 12 percent and recorded its best month since 1987.

For more than 100 years, May Day has seen celebrations of workers and workers’ rights, and has commonly been a day on which demonstrations and protests occur. Today, workers at Amazon, Whole Foods, Instacart, Walmart, FedEx, Target, and Shipt are protesting unsafe working conditions amid the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, the governors of both Texas and Iowa stated that when businesses are allowed to open back up, those who do not report to work can be terminated, even if they stay at home due to safety concerns. Dick Kovacevich, who ran Wells Fargo & Co., said that “we’ll gradually bring those people back and see what happens. Some of them will get sick, some may even die, I don’t know. Would you rather take an economic risk or a health risk? You get to choose.” Mitch McConnell flat out said he wants to shield businesses from lawsuits related COVID-19.

We’re supposed to believe that saving the economy is a concern on par with slowing the pandemic, and that in order to save the economy, we have to send people back to work. This is not the case as evidenced by the responses of many other countries. Denmark and the Netherlands each announced plans to pay up to 90 percent of wages for workers at companies affected by the pandemic. Great Britain also stepped in to pay wages. Meanwhile, our insufficient and poorly executed response has created loopholes for irresponsible actors and massive corporations to benefit.

It’s a response that only exacerbates longstanding trends — all of which are worth noting this May Day. America is a place where corporations and shareholders have immense power and workers do not. This is partly because of an erosion of social insurance programs. It’s also because unions, the primary tool by which employees can have some say over how their workplace functions, have been under assault for decades. Unionization peaked in 1954 at 28.3 percent percent of the workforce. Now, only 10.3 percent of all workers and only 6.2 percent of private workers are in a union. Unions have traditionally been the most effective way for workers to effect change in their workplace.

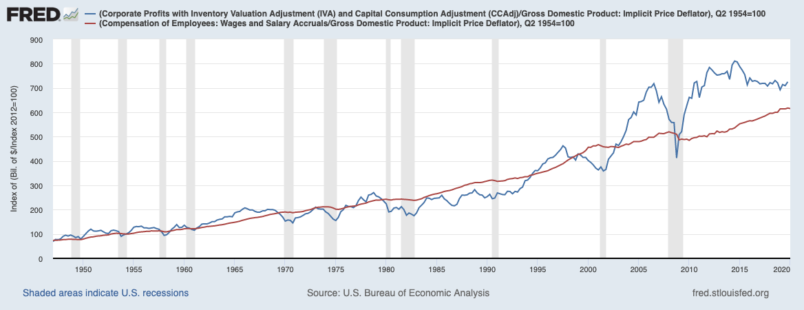

One result of this increase in corporate power is an increase in the share of profits going to those who own corporations. Over the last few decades, profits have shifted away from workers and toward shareholders.

Another effect of this shift is the ability of those who already have financial and political power to amass further financial and political power — also, often, at the expense of workers.

“Over the past two decades, administrative agencies have used legal rules, guidance documents, and court orders to mandate that private firms in these and other industries perform the duties of a public regulator,” explains a new paper published today from the Virginia Law Review. Titled “The New Gatekeepers: Private Firms as Public Enforcers,” it explains how we’ve allowed some corporations to become so big, and have so much power, the government essentially needs them to regulate aspects of society.

What could go wrong when large companies who are profit-driven regulate themselves? “By public mandate, Facebook monitors app developers’ privacy safeguards, Citibank audits call centers for deceptive sales practices, and Exxon reviews offshore oil platforms’ environmental standards,” Rory Van Loo, the author of the paper, notes.

As we face the most severe public health crisis of our lives, ask yourself: Do you want private businesses such as these regulating themselves? We should use this time to seriously evaluate the political power private companies wield. Instead, we are handing more over.

I’ve written extensively about why many bad media executives are so bad. It’s often because they don’t understand journalism as a product and therefore can’t build a business around it. In some cases, they aren’t even interested in journalism as a product at all, they just want to cut costs by any means necessary to generate profits.

This isn’t limited to the media industry though. Across industries, the modern CEO essentially has one job: grow profits.

That helps explain why the airline industry recently came to terms with the Trump administration for a $25 billion bailout package — after the major four airlines spent more than $43 billion on share buybacks, essentially using profits to simply buy the company’s own shares to increase the share price

Unfortunately for workers, a good way to generate profits is to spend as little money as possible. It’s far easier to pay people as little as possible when you don’t need to offer benefits and can keep wages low. If you can gain enough market share that you don’t really have competitors, like Amazon, even better. Lobbying the government in ways that create legal monopolies or reduce regulatory costs are also wonderful. It’s natural, then, for workers’ rights to be trampled, or to be ignored.

Trump’s recent decision to reopen meat packing plants is a perfect distillation of large private businesses working in tandem with government and ignoring workers. Contrast these two sentiments from a recent Associated Press article:

“They are so thrilled,” Trump said Wednesday after getting off a call with meatpacking executives. “They’re so happy. They’re all gung-ho, and we solved their problems.”

And now, a worker:

“Does it make sense to have meat in the markets if it takes the blood of the people who are dying to make it every day?” asked Menbere Tsegay, a worker at the Smithfield Foods plant in South Dakota, where more than 800 workers have confirmed cases of COVID-19. Two people have died, and the plant has been shut down since mid-April.

Part of the myth of the American identity is the extreme loathing of government. Somewhere in our history, government came to mean, specifically, the state. Private government, or the private sector, was positively not the government. The idea of private government, i.e. an institution that controls a large portion of our lives, has never been more important than it is now.

In “Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (And Why We Don’t Talk About It),” Elizabeth Anderson discusses at length how the free market, as imagined by 18th and 19th century thinkers such as Adam Smith and Thomas Paine, was supposed to be a “levelling” force that gave more liberty to individuals. They imagined a society comprised mostly of people who worked for themselves, or companies that were quite small. Smith’s famous pin factory in which he explained his theory of division of labor had 10 people and it was thought to be large. The massive corporations of today and the power they exert do not reflect that vision. But, as Andersen explains:

We do not live in the market society imagined by Paine and Lincoln, which offered an appealing vision of what a free society of equals would look like, combining individualistic libertarian and egalitarian ideals. Government is everywhere, not just in the form of the state but even more pervasively in the workplace. Yet public discourse and much of political theory pretends this is not so.

In our quest to eschew one form of tyranny, Anderson explains, we have created another.

Tyranny is a strong word. But it’s difficult to conjure a more accurate term for a system in which you have to show up somewhere suspecting you may then become gravely ill, or face punishment. While many on the right may eschew the state, they certainly don’t mind powerful governments forcing you to do things you don’t want.