On March 15, 1965, a week after Alabama state troopers brutally attacked civil rights protesters in Selma, President Lyndon Johnson delivered a stirring speech to a joint session of Congress introducing a bill to end voter discrimination against blacks.

The law that it gave birth to, the Voting Rights Act, now hangs in the balance, with oral arguments next week before the Supreme Court. Five conservative justices are skeptical that a centerpiece of the nearly-half-century-old law is constitutional.

“I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy,” Johnson said that night, nearly half a century ago. “A century has passed, more than a hundred years, since equality was promised. And yet the Negro is not equal. A century has passed since the day of promise. And the promise is unkept. The time of justice has now come.”

Days later, he submitted legislation to Congress aimed at taking stringent, unprecedented steps to end voter discrimination and disenfranchisement. As Congress took it up, opponents rebelled.

“I said it was worse than the Thaddeus Stevens legislation during Reconstruction, sir, and it is,” said Leander Perez, a pro-segregation Louisianan, at a subsequent Senate hearing. “It is the most nefarious — it is inconceivable that Americans would do that to Americans.”

Despite its intensity, the opposition failed. The Voting Rights Act overwhelmingly passed Congress that summer and was signed into law by Johnson on Aug. 6, 1965. A key part of the law, Section 5, required a slew of state and local governments with a history of voter discrimination to receive preclearance from the Justice Department before changing their voting laws. Today it is widely credited for helping minority voters participate equally in elections. The law played a key role in ending voter suppression tactics such as literacy tests and poll taxes.

“After a century of flouting the 15th Amendment, Congress acted to use its powers to protect the right to vote from racial discrimination,” said David Gans of the liberal-leaning Constitutional Accountability Center. “It is now seen as probably the most important federal civil rights law — one that sought to realize the promise of multiracial democracy.”

South Carolina soon led a legal challenge to key portions of the law, including Section 5. Recourse was sought directly from the Supreme Court, bypassing the lower federal courts. The Supreme Court accepted the case.

“Congress has attempted to suspend South Carolina’s literacy requirement regardless of race,” read the state’s brief. “Under the Act, at the Defendant’s direction, both white and Negro illiterates are now being registered to vote. Race, under the Act’s suspension, is not a factor. The Act absolutely grants the right to all illiterates in South Carolina to participate in her elections.”

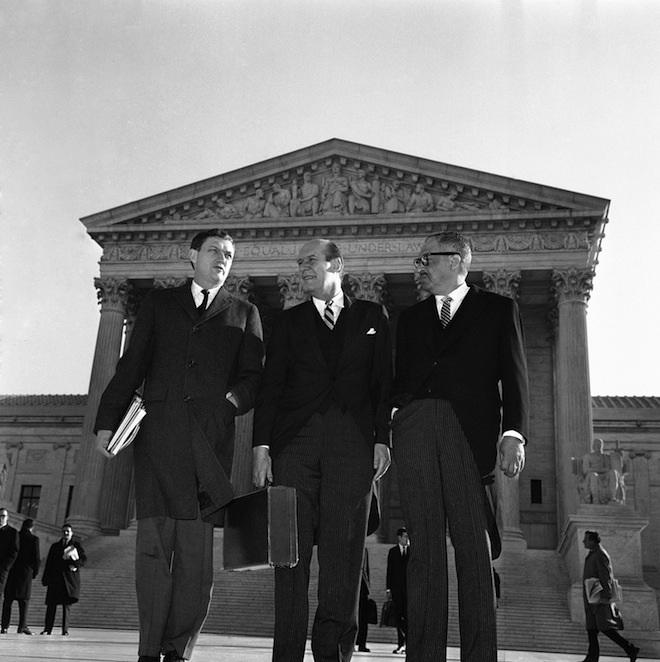

The solicitor general who defended the law on behalf of the federal government was Thurgood Marshall. Some dozen years earlier Marshall, as chief counsel of the NAACP, had argued and won the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school segregation case. A year after defending the Voting Rights Act, Johnson would name Marshall to the Supreme Court, making him the nation’s first black justice.

“In these states, there has been a policy of overt or covert obstruction with respect to the enforcement of the 15th Amendment [which prohibits voter discrimination],” Marshall said during the 1966 oral argument before the Supreme Court, referring to the states covered by the Section 5 preclearance provision. “Moreover, as a matter of common sense and reasoned judgment, it would be extreme optimism or naivete to assume that in states where there has been long enduring policies of racial discrimination, that even well disposed officials could assure the fair administration of such tests on a local level.”

The legal challenge to the Voting Rights Act in South Carolina v. Katzenbach failed, 8-1. The court proceeded to reaffirm the validity of the law three more times — in 1973, 1980 and 1999. Meanwhile, Congress repeatedly reauthorized it, with Section 5 intact, most recently in in 2006, for a period of 25 additional years.

That monument of history faces its toughest test yet next Wednesday in the Supreme Court.

Lawyers for Alabama’s Shelby County will argue for invalidating Section 5 before the most conservative bench since the law passed. Five justices have signaled their misgivings with that provision, notably Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy in 2009 when the high court ruled in favor of a Texas jurisdiction seeking an exemption from preclearance.

The challengers today concede that the Voting Rights Act was necessary at the time to rectify the scourge of racism in voting laws. But they argue that the preclearance requirement has worked so well it now discriminates against the mostly southern regions that are covered.

“There should be no question that this is constitutional, and the fact that this idea [that it might be overturned] has been raised is a reflection that we have a very ideological court,” said Caroline Fredrickson, president of the American Constitution Society, a liberal law and public policy group which supports the Voting Rights Act. “I’m hoping wiser heads prevail and the Court recognizes that it needs to be deferential to Congress’ actions.”