Health care reformers have a number of arguments for the public option, but the main one is this: that by injecting fairness and competition into the market the public option will lower premiums for everybody, including those paying for private plans. Unfortunately, a new CBO study finds that it may not have that effect at all.

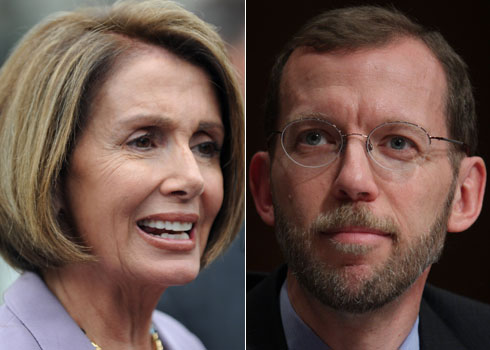

The theory behind the public option is that, by injecting a major non-profit insurer into the marketplace, it will force private competitors to cut down on administrative waste and other excesses, and, therefore, drive premiums down for everybody. Last week, when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was on the verge of losing the fight for a muscular public option, she said “There’s no philosophical difference between a robust public option and negotiated rates. It’s just a difference in money.”

But is that true? Yesterday, in an analysis of House health care legislation, the CBO concluded that the six million people expected to enroll in the public option by 2019 will be paying, on average, higher premiums than will people buying private plans.

“[A] plan paying negotiated rates would attract a broad network of providers but would typically have premiums that are somewhat higher than the average premiums for the private plans in the exchanges,” wrote CBO chief Doug Elmendorf.

The rates the public plan pays to providers would, on average, probably be comparable to the rates paid by private insurers participating in the exchanges. The public plan would have lower administrative costs than those private plans but would probably engage in less management of utilization by its enrollees and attract a less healthy pool of enrollees. (The effects of that “adverse selection” on the public plan’s premiums would be only partially offset by the “risk adjustment” procedures that would apply to all plans operating in the exchanges.)

Two things are happening here. The first is that private insurers will continue to game the system, by cherry picking for healthier customers.

“The House bill does a very good job of setting up rules restricting cherry picking,” says Edwin Park, a senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. But, he adds, “private insurers have years of experience gaming rules,” and will continue to do so.

“Insurers, just in terms of how they do outreach, how they market, are still going to be able to cherry pick,” Park says.

The second is that the public option will just be a gentler creature–it won’t erect as many restrictions on available providers and services as its private competitors will, and that’s likely to attract riskier consumers.

Overall, the impact of both phenomena is that, on average, sicker people will be drawn to (or nudged toward) the public plan, and, to be actuarially sound, it will have to raise its premiums.

The House bill does quite a bit to correct for these effects–it mandates that plans offer a minimum benefits package, and sets up a system of “risk adjustment”, to force insurers that cover relatively healthy people to help offset the cost of covering sick people. But, as CBO’s findings indicate, these provisions will probably not be enough.

This was the basis of the argument for tying the public option’s payment rates to Medicare’s. Not only would the public option save money on administrative costs, it would save yet more money by paying less to providers.

“The idea has always been that if the public option were able to save on administrative costs and provider rates, that it would be able to provide more competition,” Park says.

So does that mean that the public option is superfluous? If it’s just a separate, but unequal insurance plan for people who need a lot of medical care, and won’t put downward pressure on premiums in the private market, what’s the point? Well, it’s possible that without the public option, these same, sick people would be paying yet more still. Additionally, as the insurance exchanges grow to include a broader, healthier segment of the population, the mix of people will be healthier, and the public plan’s negotiating power will increase. But it’s certainly a weaker animal than it could have been.

Park says the best hope for reform is to create strong regulations and a strong public option, and the worst hope for reform is to create weak regulations and no public option–and that the House performs much better on this score than the Senate does. But was Pelosi right? That there’s no philosophical (or, at least, theoretical) difference between a public option that sets rates, and a public option that negotiates them? This CBO report suggests otherwise.