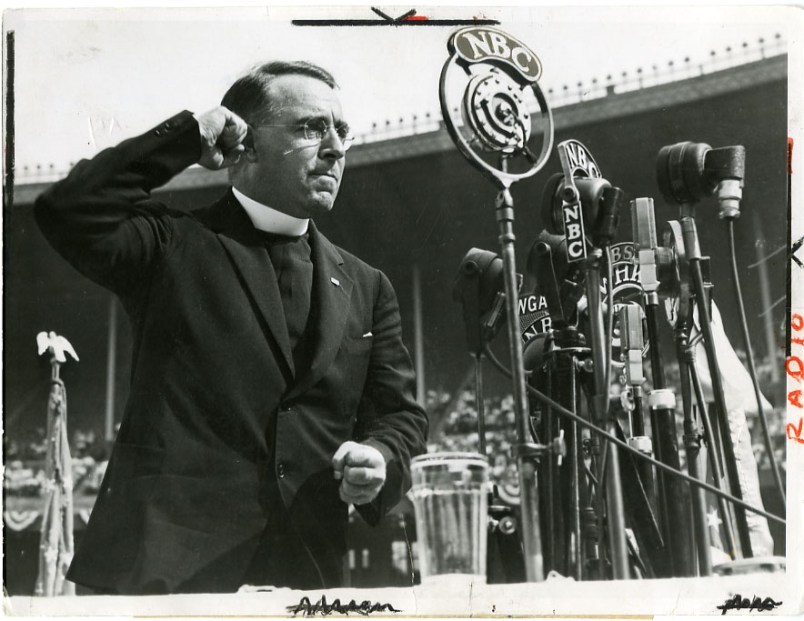

“It was a voice of mellow richness,” the great novelist Wallace Stegner remembered, “such manly, heart-warming intimacy, such emotional and ingratiating charm, that anyone tuning past it automatically returned to hear it again. … It was,” he concluded, “a voice made for promises.”

That voice, with its warm Irish brogue, belonged to Father Charles E. Coughlin, or as he was popularly known in the 1930s, “the Radio Priest.”

The pastor of a small parish in Royal Oak, Michigan, Coughlin had begun broadcasting sermons on Detroit’s WJR in an effort to counteract the anti-Catholic bigotry of the Ku Klux Klan. When the Great Depression began, however, Coughlin used his radio pulpit to speak out on political and economic issues.

He quickly attracted a massive following. By the end of 1932, Coughlin’s weekly audience was 30 to 45 million; by 1934, it was the largest radio audience in the world. Coughlin received more mail than the President of the United States and, for that matter, more than anyone in the country.

Initially, Coughlin was a strong supporter of the New Deal, using religious rhetoric to build support for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s programs. Referencing a recent film, he assured voters that “Gabriel is over the White House, not Lucifer.” Throughout 1933, Coughlin asserted “the New Deal is Christ’s Deal,” and insisted the country had just two choices before it: “Roosevelt or Ruin.”

However, in early 1934, Coughlin broke sharply with FDR. He claimed that Roosevelt – or “Franklin Double-Crossing Roosevelt,” as he called him now – was on the wrong side of history. Because the New Deal sought to reform rather than replace capitalism, Coughlin claimed it was nothing more than “a government of the bankers, by the bankers, and for the bankers.”

Father Coughlin hoped to join forces with other critics of the New Deal to mount a radical challenge to Franklin Roosevelt. However, their plans collapsed when Senator Huey Long of Louisiana, the likely face of that challenge, was assassinated in September 1935. Still, Coughlin continued to act on his own, as seen in this newsreel, which appeared shortly before the 1936 election.

As Coughlin’s attacks on bankers became increasingly anti-Semitic, his popularity waned. When the Second World War began, his isolationism and comments supporting the Axis Powers made him ever more marginalized at home. In 1940, the National Association of Broadcasters adopted new policies restricting radio time for “spokesmen of controversial public issues.” Those rules, everyone knew, had been made with the Radio Priest in mind. By the end of the year, Coughlin found his voice effectively silenced.

When his superiors in the Catholic Church insisted he end his remaining political activity, Coughlin retreated to his small parish in Royal Oak. He lived there, for the next quarter century, in quiet obscurity.

Father Coughlin, aka Rush Limbaugh v1.0