This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

Workers organized and took to the picket line in increased numbers in 2022 to demand better pay and working conditions, leading to optimism among labor leaders and advocates that they’re witnessing a turnaround in labor’s sagging fortunes.

Teachers, journalists and baristas were among the tens of thousands of workers who went on strike — and it took an act of Congress to prevent 115,000 railroad employees from walking out as well. In total, there have been at least 20 major work stoppages involving at least 1,000 workers each in 2022, up from 16 in 2021, and hundreds more that were smaller.

At the same time, workers at Starbucks, Amazon, Apple and dozens of other companies filed over 2,000 petitions to form unions during the year — the most since 2015. Workers won 76% of the 1,363 elections that were held.

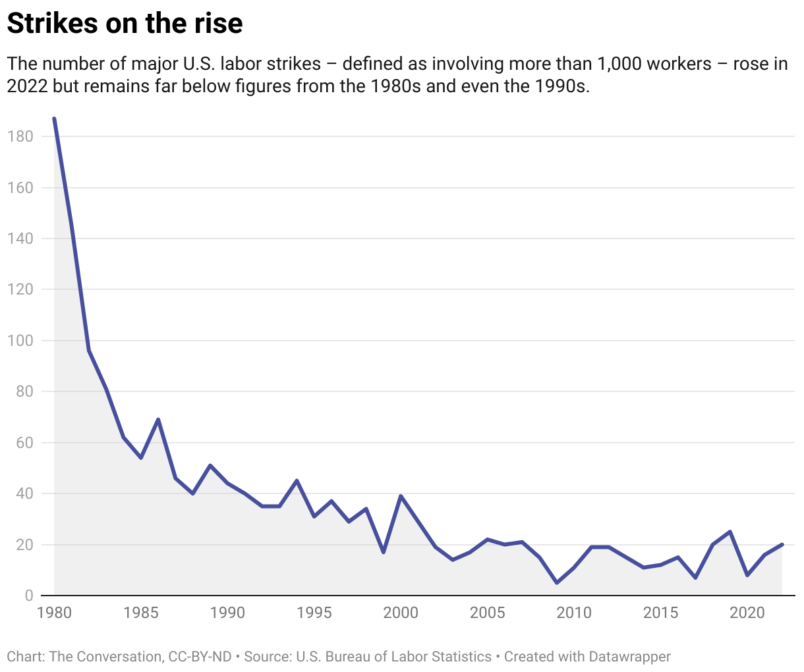

Historically, however, these figures are pretty tepid. The number of major work stoppages has been plunging for decades, from nearly 200 as recently as 1980, while union elections typically exceeded 5,000 a year before the 1980s. As of 2021, union membership was at about the lowest level on record, at 10.3%. In the 1950s, over 1 in 3 workers belonged to a union.

As a labor scholar, I agree that the evidence shows a surge in union activism. The obvious question is: Do these developments manifest a tipping point?

Signs of increased union activism

First, let’s take a closer look at 2022.

The most noteworthy sign of labor’s revival has been the rise in the number of petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board. In fiscal year 2022, which ended in September, workers filed 2,072 petitions, up 63% from the previous year. Starbucks workers alone filed 354 of these petitions, winning the vast majority of the elections held. In addition, employees at companies historically deemed untouchable by unions, including Apple, Microsoft and Wells Fargo, also scored wins.

The increase in strike activity is also important. And while the major strikes that involve 1,000 or more employees and are tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics arouse the greatest attention, they represent only the tip of the iceberg.

The bureau recorded 20 major strikes in 2022, which is about 25% more than the average of 16 a year over the past two decades. Examples of these major strikes include the recent one-day New York Times walkout, two strikes in California involving more than 3,000 workers at health care company Kaiser Permanente, 2,100 workers at Frontier Communications and 48,000 workers at the University of California.

Since 2021, Cornell University has been keeping track of any labor action, however small, and found that there were a total of 385 strikes in calendar year 2022, up from 270 in the previous year. In total, these reported strikes have occurred in nearly 600 locations in 19 states., signifying the geographic breadth of activism.

Historical parallels

Of course, these figures are still quite low by historical standards.

I believe two previous spikes in the early 20th century offer some clues as to whether recent events could lead to sustained gains in union membership.

From 1934 to 1939, union membership soared from 7.6% to 19.2%. A few years later, from 1941 to 1945, membership climbed from 20% to 27%.

Both spikes occurred during periods of national and global upheaval. The first spike came in the latter half of the Great Depression, when unemployment in the U.S. reached as high as a quarter of the workforce. Economic deprivation and a lack of workplace protections led to widespread political and social activism and sweeping efforts to organize workers in response. It also contributed to the enactment of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which stimulated organizing in the industrial sector.

The second jump came as the U.S. mobilized the economy to fight a two-front war in Europe and Asia. National economic mobilization to support the war led to growth in manufacturing employment, where unions had been making substantial gains. Government wartime policy encouraged unionization as part of a bargain for industrial peace during the war.

Inequality and pandemic heroes

Today’s situation is a far cry from the economic misery of the Great Depression or the social upheaval of a global war, but there are some parallels worth exploring.

Overall unemployment may be near record lows, but economic inequality is higher than it was during the Depression. The top 10% of households hold over 68% of the wealth in the U.S. In 1936, this was about 47%.

In addition, the top 0.1% of wage earners experienced a nearly 390% increase in real wages from 1979 to 2020, versus a meager 28.2% pay hike for the bottom 90%. And employment in manufacturing, where unions had gained a stronghold in the 1940s and 1950s, slipped over 33% from 1979 to 2022.

Another parallel to the two historical precedents concerns national mobilization. The pandemic required a massive response in early 2020, as workers in industries deemed essential, such as health care, public safety and food and agriculture, bore the brunt of its impact, earning them the label “heroes” for their efforts. In such an environment, workers began to appreciate more the protections they derived from unions for occupational safety and health, eventually helping birth much-hyped recent labor trends like the “great resignation” and “quiet quitting.”

A stacked deck

Ultimately, however, the deck is still heavily stacked against unions, with unsupportive labor laws and very few employers showing real receptivity to having a unionized workforce.

And unions are limited in how much they can change public policy or the structure of the U.S. economy that makes unionization difficult. Reforming labor law through legislation has remained elusive, and the results of the 2022 midterms are not likely to make it any easier.

This makes me unconvinced that recent signs of progress represent a turning point.

An ace up labor’s sleeve may be public sentiment. Support for labor is at its highest since 1965, with 71% saying they approve of unions, according to a Gallup poll in August. And workers themselves are increasingly showing an interest in joining them. In 2017, 48% of workers polled said they would vote for union representation, up from 32% in 1995, the last time this question was asked.

Future success may depend on unions’ ability to tap into their growing popularity and emulate the recent wins at Starbucks and Amazon, as well as the successful “Fight for $15” campaign, which since 2012 has helped pass $15 minimum wage laws in a dozen states and Washington, D.C.

The odds may be steep, but the seeds of opportunity are there if labor is able to exploit them.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.