In November, Ohioans gave Republican legislators a shellacking on abortion rights, enshrining the right to the procedure (as well as rights to contraception, in-vitro fertilization and miscarriage care) in the state’s constitution. Though Ohio voters consistently elect Republicans in statewide races, the referendum passed by a margin of 14 percentage points. The vote — together with similar results in Kansas and Kentucky — has rightly been seen as a warning that Republicans in state legislatures, Congress and on the Supreme Court bench are radically out of step with the citizenry on this issue, even in reliably red states.

The vote on Ohio’s referendum was geographically split along patterns the pioneering Midwestern political geographer Frederick Jackson Turner would have recognized in 1895. Every county in the New England-settled northeast voted overwhelmingly in favor, rural and urban alike. A middle section of the state, where colonization was led by Pennsylvania “Dutch” and German immigrant farmers, opposed the measure, which only barely passed in its cities. The Scots-Irish-settled south of the state, first colonized via western Virginia and Kentucky, left Columbus, Cincinnati, and Ohio University as islands poking from a sea of opposition.

To understand why so many red state leaders, in defiance of their own electorates, have moved to enact laws to ban abortion or even to prosecute people seeking or providing the procedure, you need to take a plunge into geography, history, and centuries-old settlement patterns that created the cross-wired political world we live in today. Absent a national abortion ban, the states in which women can terminate an unwanted pregnancy will largely be determined by the legacy of events, migrations, and conquests in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries and the political science incentives they created in some places and not in others.

Modern politics and policies make more sense when viewed through the regional identities that are the legacy of America’s early colonial projects. In my 2011 book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, I explained how mutually exclusive bands of immigration imbued their respective regions with civic and religious institutions, cultural norms and ideas about freedom, social responsibility and the provision of public goods that later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into. These settlement streams — whose members were often repelled by one another’s values and practices — spread with little regard for today’s state (or even international) boundaries.

Those colonial projects — Puritan-controlled New England; the Dutch-settled area around what is now New York City; the Quaker-founded Delaware Valley; the Scots-Irish-dominated upland backcountry of the Appalachians; the West Indies-style slave society in the Deep South; the Spanish project in the southwest and so on — had different religious, economic and ideological characteristics. They settled much of the eastern half and southwestern third of what is now the U.S. in mutually exclusive settlement bands before significant third party in-migration picked up steam in the 1840s. In the process — as I unpacked in American Nations — they laid down the institutions, cultural norms and ideas about freedom, social responsibility and the provision of public goods that later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into. Some states lie entirely or almost entirely within one of these regional cultures (Mississippi, Vermont, Minnesota and Montana, for instance). Other states are split between the regions, propelling constant and profound internal disagreements on politics and policy alike in places like Pennsylvania, Illinois, California, Oregon and, yes, Ohio.

The American Nations model of U.S. Regions

In the book American Nations, I argued that there has never been one America but rather several Americas, most of them developing from one or another of the rival colonial projects that formed on the eastern and southwestern rims of what is now the United States. These regional cultures — “nations,” if you will — had their own ethnographic, religious and political characteristics, distinct ideas about the balance between individual liberty and the common good and what the United States should become.

The nine large regions — with populations today ranging from 13 and 63 million — are:

Yankeedom (pop. 55.8 million)

Founded by Puritans who sought to perfect earthly society through social engineering, individual denial for the common good, and the assimilation of outsiders. The common good — ensured by popular government — took precedence over individual liberty when the two were in conflict.

New Netherland (pop. 18.8 million)

Dutch-founded and retains characteristics of 17th century Amsterdam: a global commercial trading culture, materialistic, multicultural and committed to tolerance and the freedom of inquiry and conscience.

Tidewater (pop. 12.6 million)

Founded by lesser sons of landed gentry seeking to recreate the semi-feudal manorial society of the English countryside. Conservative with strong respect for authority and tradition, this culture is rapidly eroding because of its small physical size and the massive federal presence around D.C. and Hampton Roads.

Greater Appalachia (pop. 59 million)

Settlers came overwhelmingly from war-ravaged Northern Ireland, Northern England and the Scottish lowlands, and were deeply committed to personal sovereignty and intensely suspicious of external authority.

The Midlands (pop. 37.7 million)

Founded by English Quakers, who believed in humans’ inherent goodness and welcomed people of many nations and creeds. Pluralistic and organized around the middle class; ethnic and ideological purity is never a priority; government is seen as an unwelcome intrusion.

Deep South (pop. 43.5 million)

Established by English Barbadian slave lords who championed classical republicanism modeled on slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was the privilege of the few and subjugation and enslavement the natural lot of the many.

El Norte (pop. 33.3 million)

Borderlands of the Spanish-American empire, so far from Mexico City and Madrid that it developed its own characteristics: independent, self-sufficient, adaptable and work-centered. Though it often sought to break away from Mexico to become an independent buffer state, it was annexed into the U.S. instead.

Left Coast (pop. 17.9 million)

Founded by New Englanders (who came by ship) and farmers, prospectors and fur traders from the lower Midwest (by wagon), it’s a fecund hybrid of Yankee utopianism and the Appalachian emphasis on self-expression and exploration.

Far West (pop. 28.7 million)

An extreme environment stopped eastern cultures in their path, so settlement largely was controlled by distant corporations or the federal government via deployment of railroads, dams, irrigation, and mines; exploited as an internal colony, with lasting resentments.

You can find a more detailed summary here, at the Nationhood Lab.

The pattern of Ohio’s vote was almost pre-ordained by this colonization history and the regional cultures it created, just as were the results of other post-Dobbs abortion measures in Michigan, Kansas, Kentucky, California, and Vermont. The same can be said of the states in which political elites have enacted unpopular and often extreme anti-abortion policies sought by a focused and influential minority that’s successfully hacked local political establishments in ways that would be impossible in other regions.

At Nationhood Lab, a project I founded at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy, we use this regional framework to analyze all manner of phenomena in American society and how one might go about responding to them. We’ve looked at everything from gun violence and attitudes toward threats to democracy to Covid-19 vaccination rates, life expectancy, the prevalence of diabetes and obesity, rural vs. urban political behavior and the geography of the 2022 midterm elections. This spring we’ve been parsing abortion opinion via the massive Democracy Fund + UCLA Nationscape poll, which from late 2019 to early 2021 asked a half million Americans about their stance on a wide range of social, political and economic questions, including abortion; we’ve dug into the county-level results of the post-Dobbs abortion initiatives across the country and overlaid them with the American Nations settlement model and the closely related religious makeup of each county as calculated by the Public Religion Research Institute in their 2020 Census of American Religion. The results – which we’ve published in wonky detail at the project website — provide a Rosetta Stone for understanding an issue that is propelling inter-regional animosity at a time when the sinews holding our federation together are weakening.

In terms of policy implementation, the geographic divide is stark. Since the Dobbs decision came down, 14 states have fully banned abortion and seven others have restricted the procedure to earlier in the pregnancy than allowed by Roe v. Wade. Together they include every state controlled, in the American Nations settlement model, by the Deep South or Greater Appalachia, plus two Far Western-controlled states and four (Missouri, the Dakotas, and Nebraska) with mixed Midlands and Far Western control. By contrast, abortion remains legal and unchallenged in every state controlled by Yankeedom, New Netherland, Tidewater, Left Coast and Greater Polynesia, and most of those states have increased protections for abortion access since the Dobbs ruling. Lawmakers in Midlands-controlled Kansas and in Ohio — with those large Yankee and Midlands sections but a Greater Appalachian plurality — wanted a ban too, but were stopped by their citizens via ballot referendum, an option most Deep Southern and Greater Appalachian states do not allow.

Officials in some states controlled by the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, the Midlands or some combination thereof want to make it a crime for one of their residents to get an abortion in another state where it’s legal, a move that encumbers women’s right to travel. Texas now allows civil suits against any entity that provides funds or assistance to someone trying to obtain an out-of-state abortion and South Dakota law opens the possibility that out-of-state medical providers could face criminal charges for filling a mail-order prescription for federally approved abortion drugs. Alabama attorney general Steve Marshall says anyone helping an Alabaman to obtain an out-of-state abortion has engaged in a criminal conspiracy. “Alabama can criminalize Alabama-based conspiracies to commit abortions elsewhere,” his office has asserted in court filings.

Meanwhile, states dominated by Yankeedom, New Netherland and Left Coast have added reproductive rights protections and declared other states’ anti-abortion laws to be inapplicable in their courts. Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey and Delaware now prohibit law enforcement from cooperating with abortion investigations or answering legal summons by anti-abortion states. Maine Gov. Janet Mills — a career state prosecutor and former state attorney general — issued an executive order prohibiting authorities from arresting or surrendering an individual for these new crimes on behalf of an anti-abortion state’s government. California lawmakers have prohibited companies, tech goliaths, and government agencies from providing personal data or medical data to out-of-state abortion investigators.

Together, these regional divides amount to what George Washington University law professor Paul Berman has called “the biggest set of nationwide conflicts-of-law problems since the era of the Fugitive Slave Act before the Civil War,” when southern states began forcing northerners to apprehend any Black person they claimed had escaped from slavery and, without due process, return them to bondage.

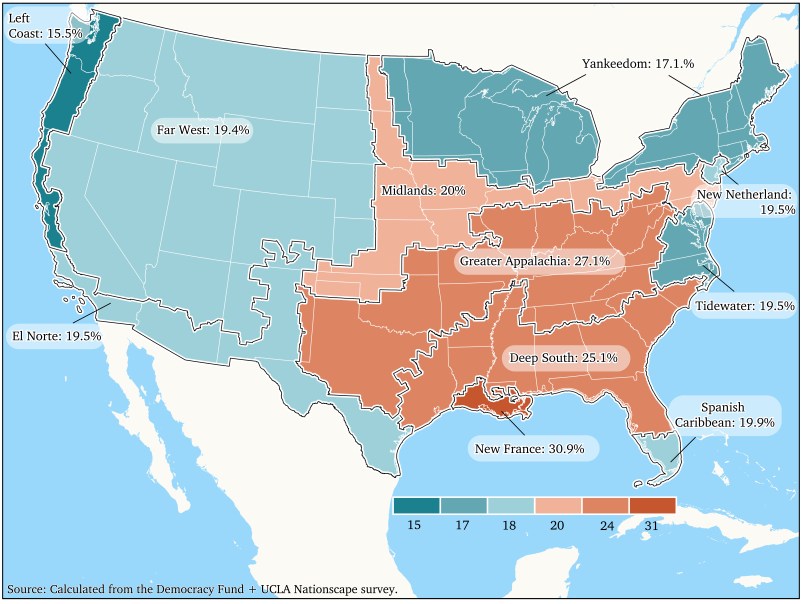

The Nationscape survey shows the public favors abortion being legal in every state and region, but the depth of that support varies in a pattern mirroring the policy divide we just described.

Supermajorities in every American Nations region reject an outright ban on abortion, and large majorities everywhere believe the procedure should be legal for reasons beyond incest, rape, and the life of the mother. But support for a total ban is nearly twice as high in New France — that’s southern Louisiana — (at 30.9 percent) than in the Left Coast (15.5 percent). The block wanting a ban is about a quarter greater in the Deep South and Greater Appalachia (where it’s a bit more than a quarter of the population) than in Yankeedom, Tidewater, El Norte, New Netherland, or Spanish Caribbean (all between 17 percent and 20 percent). We found a very similar pattern when probing opposition to abortions for reasons other than rape, incest, or saving the life of the mother.

Abortion ban support by regional culture

Who are these abortion opponents? Far and away the biggest predictor, no matter what region we looked at, was being a white Evangelical. Depending on region, 38 to 47 percent of this cohort supports a total ban, compared to 19 to 34 percent for Catholics and 6 to 14 percent for mainline Protestants (with New France as an outlier among Protestants at 25 percent). We found one’s religious affiliation has a much greater effect on abortion opinion than their gender — indeed, in the South there’s hardly any gender gap at all. And the religious geography of this country has, to a degree seldom appreciated, been determined by the distinct value systems of the settlement

White Evangelicals, the PRRI data reveals, are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Deep South and Greater Appalachia, where they constitute 31 and 24 percent of the overall population respectively. (They are 14 percent of the national population and only three percent of New Netherland’s.) That Evangelicals dominate in the Bible Belt probably comes as no surprise, but it’s the way Evangelical Protestantism took root in the South that has made such a difference in modern abortion politics.

In the 18th century, most of the South was, in fact, the least likely place for Evangelicals to find favor. In Virginia (which included today’s West Virginia), the Carolinas and Georgia, the Church of England (rebranded as the Episcopal church after the Revolution) was the official, taxpayer-financed church. Few people responded well to Evangelical Baptist and Methodist preachers from Yankeedom, the Midlands, New Netherland and Great Britain who demanded that followers stop drinking, gambling, swearing and fighting. These early Evangelicals were even more unpopular in the lowlands because they threatened that region’s power structure, casting aspersions on slavery, welcoming African-Americans into fellowship and encouraging followers to regard one another as family, regardless of race, class or marital status.

“Evangelicals, far from dominating the South, were viewed by most whites as odd at best and subversive at worse,” writes University of Delaware historian Christine Leigh Heyrman, author of Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt.

In the early 19th century, however, Evangelical missionaries adapted to the southern cultures, accepting slavery, the racial segregation of churches, strong patriarchal family dynamics, and the private misconduct of men. Southern Evangelical camp meetings adopted a manly, martial vibe that accorded with the southern “culture of honor,” with morning bugle calls, marches to the altar, and posted rules enforced by “dog-whippers,” guards with special insignia attached to their coats who patrolled the grounds. In the Antebellum Era, southern Baptists and Methodists would break from their northern counterparts over their support of slavery, which is why there’s a Southern Baptist Convention in the first place. These adaptations caused their religion to spread rapidly across these cultural regions, helped by the fact most Anglican priests had fled to England when the American Revolution broke out, leaving their congregations ripe for poaching.

“It’s not too much of an oversimplification to say that what happens in the South between 1780 and the Civil War is that the religion, Evangelicalism, adapts to the culture,” Heyrman told me. “The Evangelicalism in the North is in many ways a very different animal than in the Evangelical South.”

In Yankeedom, the Midlands and New Netherland, Evangelicals faced ever-increasing competition from other groups, both home-grown rivals like the Mormons, Seventh Day Adventists, or Christian Scientists and immigrant-powered Catholic, Lutheran, Orthodox Christian, and Jewish congregations. And without the same cultural incentives as their southern co-religionists faced, many northern Baptist and Methodist groups became “mainline” Protestant over time, in that they read many Biblical passages as allegory and metaphor rather than being literally true. The gulf between the regions grew dramatically during the great immigration wave of 1880 to 1924 because the three southern regions’ feudal nature repelled the newcomers, causing them to be nearly bereft of Catholics, Jews, Orthodox Christians and other non-Evangelicals until the 1980s. Right into the late 1960s, Evangelicalism was practically the only show in town, and enjoyed the power of incumbency to a degree unmatched elsewhere.

Immigrants per capita, 1900

Dominant religion, U.S. counties, 2020

There is one big American Nations region — the Midlands — whose settlement history and underlying cultural ethos presents something of a wild card in mapping abortion opinion.

This region has always had an extremely heterogenous religious identity thanks to its Quaker founders, who welcomed people of many nationalities and religious denominations — some conservative, some liberal — to their multicultural colonies on Delaware Bay. That multicultural ethos was enhanced by new streams of religious refugees in the mid- to late-19th century. The result was that in the Midlands, more so than any other region, different ethno-religious communities were encouraged to erect their own villages, towns and neighborhoods and maintain their linguistic, cultural and spiritual practices, with a lasting imprint you can see today, from Pennsylvania to Iowa.

This matters for today’s abortion politics because it has made the Midlands more like a chunky stew than a melting pot. The presence of white Evangelicals is still your best tool for predicting how a given Midlands county will vote, but there are concentrations of centuries-old religious communities of surprising homogeneity that sometimes have very strong opinions on abortion. That’s why the Midlands band in Ohio, which features a constellation of deeply conservative German Catholic settlements combined with a percentage of white Evangelicals, voted to reject the abortion initiative by seven points.

But in Kansas, 8 out of 10 Midlanders live in metropolitan areas, and in Kansas City, Wichita and Topeka (unlike Toledo and Youngstown in Ohio), pro-life mainline Protestants outnumber both Catholics and white Evangelicals. In the 2022 vote, the Kansas Midlands supported abortion by double digits, spearheading its passage over the objections of the state’s much less populous Greater Appalachian and Far Western sections. In this regard, the Missouri Midlands look a lot more like Kansas than Ohio and, given that that section of the state makes up two-thirds of the electorate, abortion restrictions will almost certainly lose at the ballot box when Missourians vote on their state’s referendum this coming November.

Republicans’ aggressive pro-life stance in Arizona may be based on moral conviction but makes absolutely no political sense. The state — divided between El Norte and Far West sections — has relatively few white (or Hispanic) Evangelicals, lots of (generally pro-choice) mainline Protestants and (ambivalent) Spanish Catholics, and even a substantial indigenous population. It’s no surprise that polls show supermajority support for abortion being legal in most cases, which wasn’t the case for Kentucky or Kansas before they voted on the issue. The Arizona state Supreme Court’s ruling earlier this spring to put back into force a total abortion ban passed by the territorial legislature in 1864 — a time when Arizona wasn’t a state and women didn’t have the right to vote — was overturned earlier this month by Democratic legislators with the help of a handful of Republican defectors, but could still go into effect for some weeks due to the quirks of state law. None of this will help GOP candidates in this fall’s elections.

Abortion will likely prevail in any state that allows ballot measures, but many states that have banned or severely restricted the procedure don’t allow citizen initiated-ballot referenda, including almost every one in the Deep South, Greater Appalachia and New France. Which leaves a big political question: If most people in these regions don’t want abortion banned or restricted, how has a white Evangelical minority been able to get their way nonetheless?

Academics have been asking this question for decades and have come to some broad conclusions. From their fight against gay marriage in the early 2000s to wanting to ban abortion today, white Evangelicals succeed in states where they’ve been able to capture intermediary institutions like state (Republican) parties, (the Republican caucuses of) legislatures, or the state’s executive branch. “Successes have been achieved,” sociologists Rebecca Sager and Keith Bentele concluded in a study of how and where faith-based legislation passed between 1996 and 2009, primarily “through effective utilization of an existing political institution, the Republican Party.”

It turns out Evangelical churches are excellent training grounds for political organizing. “Places of worship provide a natural foundation for organizing, a place where people are showing up every week and maybe serving on a board or volunteering at all sorts of events,” says Christopher Scheitle, assistant professor of sociology at West Virginia University, who found Christian Right influence within state GOPs had an even greater influence on the passage of anti-LGBTQ adoption, discrimination, hate crime and marriage laws from 2005 to 2008 than the proportion of a state’s population that were Evangelical. “And Evangelical churches have this entrepreneurial spirit and they don’t have to seek approval from a hierarchy of a bishop to set up associated non-profits like sports camps or publishing houses, which get people in the pews involved,” Scheitle says.

An organized minority can get a long way, but numbers still matter. It’s one thing to capture a state political party, legislative majority, or gubernatorial administration if you’re group represents 20 or 30 percent of the population, quite another if it’s only 2, 8 or 10 percent, which is why white Evangelicals are not getting their way in New Netherland and Yankeedom.

“It doesn’t matter if you want something if those in power who can make that happen aren’t willing to listen to you,” Scheitle adds. “But if those in power have an affinity with or, for whatever reason, find it useful to listen to a particular part of the population, that’s where you see these social movements succeed.”

Abortion bans are highly unpopular but right wingers support them because they know their voters will pick them anyway. It’s that simple.

The only way to kill off the bans are for Republicans to lose in deep red states, and that’s not happening.

I agree. I have a family member who always votes Republican even though they are pro abortion rights. They even have a daughter who is an OB-GYN and provides abortion care services! I don’t get it.

TYPO ALERT:

But in Kansas, 8 out of 10 Midlanders live in metropolitan areas, and in Kansas City, Wichita and Topeka (unlike Toledo and Youngstown in Ohio), pro-life mainline Protestants outnumber both Catholics and white Evangelicals.

pro-life mainline Protestants makes no sense here and should almost certainly be pro-choice mainline Protestants

It’s frustrating to me when pundits go on about abortion as an issue for voters but never look at what that means at the ballot box. Greg Abbott got re-elected after SB8. The question needs to really be asked as, “Do you care enough about abortion access that it will dictate your vote?”

So, even in the “New France” area (New Orleans) per the map below, with abortion opposition at around 30%, this shows tyranny by the minority. As we all know here, abortion rights are supported by a majority of voters.