The Supreme Court ruled Thursday that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional, overturning decades of precedent.

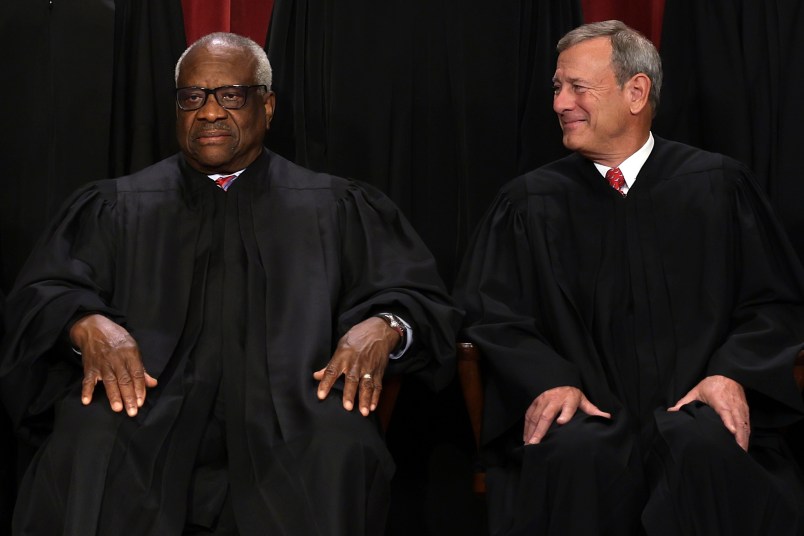

“Harvard’s and UNC’s admissions programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority.

He was joined by the rest of the right-wing justices. Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, joined by Justice Elena Kagan in full and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson in part (Jackson had recused herself from Harvard’s case due to her ties to the school). Jackson also wrote in dissent, joined by Sotomayor and Kagan. Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch all also wrote concurring opinions.

Roberts writes a couple lines that seem to all but eliminate race-conscious admissions completely: “Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin. This Nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.”

He spends considerable time critiquing the liberals’ dissents, at one point saying of Sotomayor’s position that the programs should continue: “That is a remarkable view of the judicial role — remarkably wrong.”

Sotomayor squarely attacks the majority for feigning colorblindness in a way that will inevitably drain colleges and universities of minority students.

“The Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter,” she writes. “The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society.”

She becomes particularly sharp when knocking down the majority’s characterization of the Brown v. Board of Education litigation.

“The Court’s recharacterization of Brown is nothing but revisionist history and an affront to the legendary life of Justice Marshall, a great jurist who was a champion of true equal opportunity, not rhetorical flourishes about colorblindness,” she writes.

Jackson devotes much of her dissent to tracking the many inequities that still plague Black Americans, from lagging home ownership to the persistent wealth and income gap between Black and white families.

“With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat,” she writes.

In his concurrence, Thomas offers an “originalist defense of the colorblind Constitution,” including the amendments written specifically with race in mind after the Civil War. He also makes a similar case to the one Gorsuch lays out in his own concurrence: that college admissions are a zero-sum game.

“Just as there is no question Harvard and UNC consider race in their admissions processes, there is no question both schools intentionally treat some applicants worse than others because of their race,” Gorsuch writes.

Kavanaugh stakes his concurrence on his argument that “race-based affirmative action in higher education” may not “extend indefinitely into the future.”

While the majority knocked down the schools’ use of race as one of many factors in determining eligibility, Roberts allows for some consideration of applicants’ race in the process.

“Nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university,” he writes.

That initial caveat was perhaps written in to placate a concern Jackson raised during oral arguments.

“Now we’re entertaining a rule in which some people can say the things they want about who they are and have that valued in the system, but other people are not going to be able to because they won’t be able to reveal that they’re Latina or African American or whatever,” she said in October 2022. “And I’m worried that that creates an inequity in the system.”

Sotomayor dismisses Roberts’ attempt to project moderation, calling it a “false promise to save face.”

“No one is fooled,” she writes.

Read the opinion here: