ARTESIA, N.M. (AP) — Trailers have been set up for a school at a federal immigration detention center in an isolated New Mexico desert town. A basketball court and a soccer field have been installed. And detainees are pleading their cases over a video link with judges in Denver.

Officials say that the facility, billed as a temporary place to house women and children from Central America who were among a wave of immigrants who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border illegally this year, could remain open until next summer.

“All of us would love us to see the doors close in Artesia but the reality is the need will probably be there and probably until the end of the high season, probably August next year,” a government official told immigration advocates in a recent confidential meeting.

The AP had access to a recording of the meeting with the official, whose name or position was not identified.

The detainees at the Artesia Family Residential Center, meanwhile, are growing increasingly frustrated that they are being held with no end in sight while earlier border-crossers were released with orders to contact immigration officials later.

“I’m being punished for coming here, they tell us,” said Geraldyn Perez. She said she fled death threats by gangs in Guatemala.

The center opened as federal officials were realizing over the summer that the thousands of border-crossers they released had disappeared into the nation’s interior and never showed up for any meetings with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

The government official in the recorded confidential meeting acknowledged that about 70 percent of the released families vanished.

The official explained to human rights activists that prolonged detention of children and mothers is “not punitive,” adding that detention is not a tool for deterring would-be immigrants, many of them who have made claims of asylum.

Instead, he said, “the deterrence is that you’re not going to come to the United States and you’re automatically here and you’ll never be removed.”

Immigration advocates say that a federal report by the Citizenship and Immigration Service’s asylum unit to activists says only 37.8 percent of the Artesia detainees pass their initial interviews for asylum, compared to the 62.7 percent national average.

And for those who are eligible for release, bonds have been set as high as $25,000 or $30,000 or about five times the national average, according to immigration lawyer Stephen Manning, who has volunteered in Artesia.

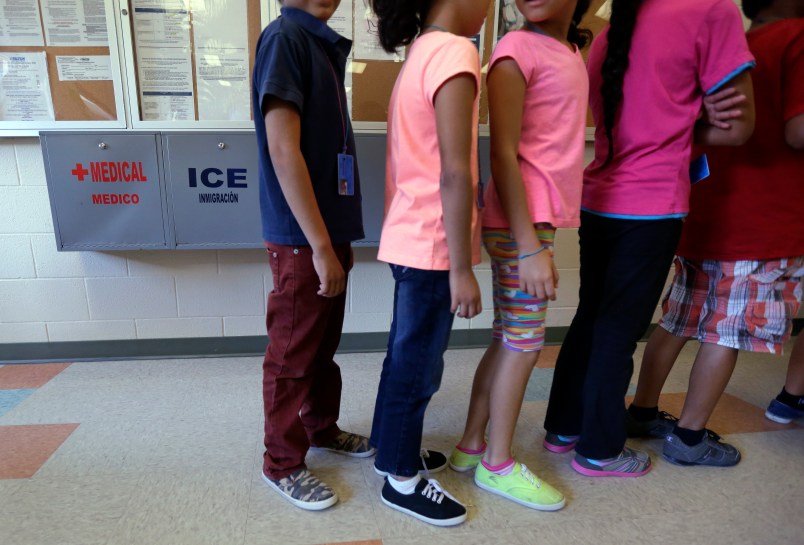

Housing more than 500 women and children at any given time, ICE said, the Artesia location remains an “effective and humane” piece in the government’s response to the unprecedented influx of adults with children arriving at the southern border.

Since the center opened in June, more than 300 women and children, mostly from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, have been deported. About 500 others remain. And since it’s opening, conditions have improved for detainees to meet with their lawyers.

Over the first few weeks, the only access to legal counsel detainees had were a video presentation about the rights of detainees. ICE is now allowing lawyers to meet with the detainees and allows them to bring in their cellphones and computers, which was forbidden.

Civil rights advocates are suing the government, complaining that a lack of access to legal representation has turned the center into a “deportation mill,” where bail is set impossibly high and asylum claims are denied at a much higher rate than the rest of the immigrant population.

“The government is taking things to an extreme that seems designed to deny people the right to present their case,” said immigration lawyer Laura Lichter, one of dozens of attorneys who provide pro-bono services to the detained families.

Lichter said bonds should be considered based on factors such as if the person poses a danger to the community and if there is risk of flight. She cited several studies by organizations that deal with asylum cases that show how asylum seekers have a near-perfect court attendance rates.

Court dates for people who are released on bond are scheduled up to two or more years into the future, giving asylum seekers more time to prepare their case from home. People in detention are given about two months before appearing in front of a judge.

Perez said her husband came to the U.S. a year ago with an asylum claim and was freed on $3,000 bond. With bonds in Artesia going 10 times that amount, she said she will likely remain locked up.

After landing in Artesia, Perez said she regrets coming to the US. She did not want to come, she said. “I wanted to live and die in Guatemala. Just not die before my time.”

She hoped for help in the U.S. But now, she said, “I so regret coming. I had these huge will to come out ahead in this country, but that’s gone here. I have nothing left.”

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.