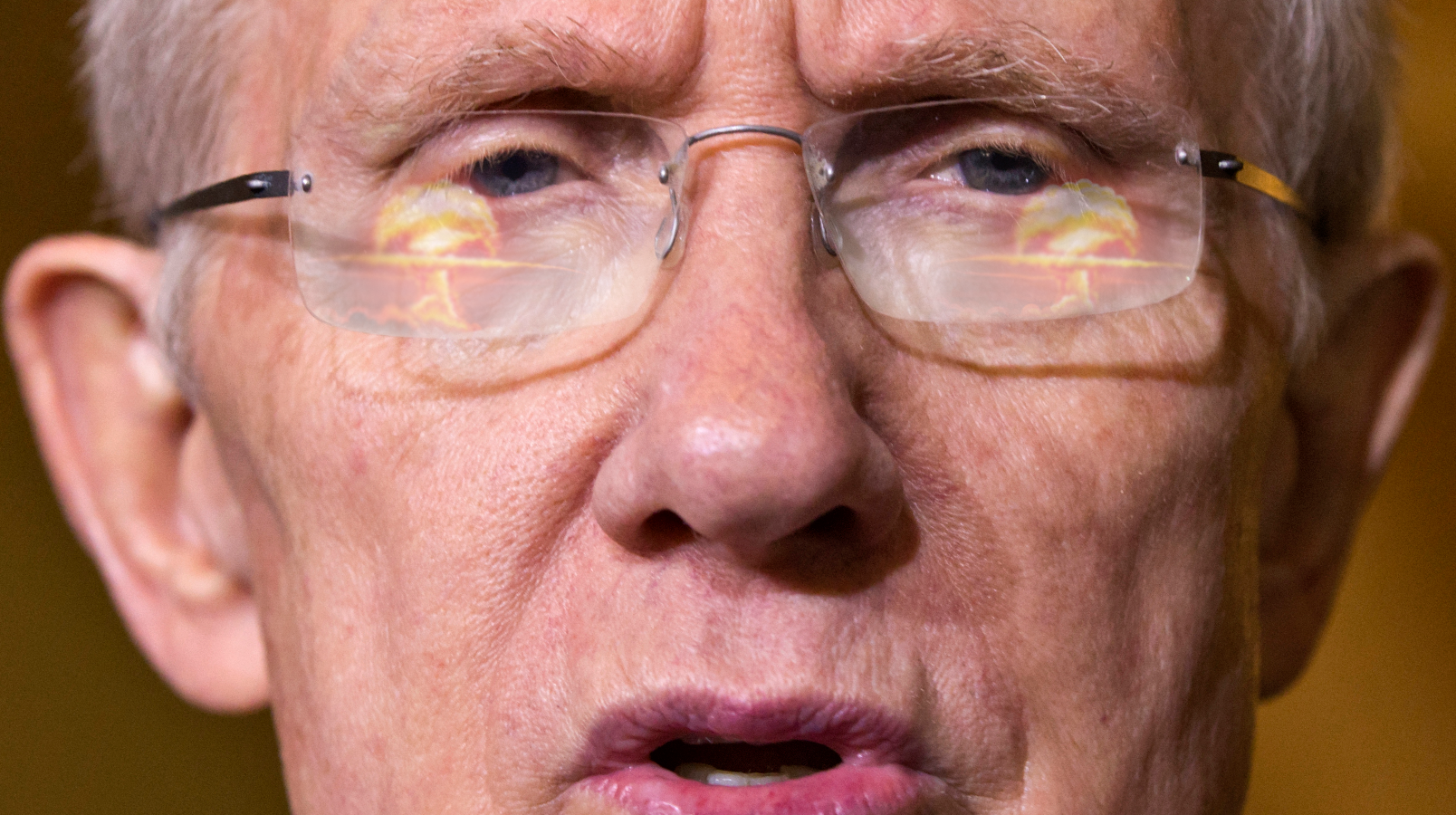

The February filibuster of Chuck Hagel was the last straw for Harry Reid.

In the eyes of the Democratic majority leader, Republicans had just shattered a mere three-weeks-old agreement to avoid a drastic change to the Senate rules. Not only was the Hagel vote the first time in U.S. history the Senate filibustered a nominee to be secretary of defense, but the minority party took an unprecedented step and rebuked one of their own: Hagel was a former red state Republican senator who also happened to be a decorated war veteran.

In the days that followed, a few things crystallized in the Nevada senator’s mind. The re-election of President Barack Obama and Republican promises of a “new day” in the Senate were all for naught. It became clear that the GOP was not going to change its practice of obstruction, which was rendering dysfunctional not only the legislative branch but also the executive and judicial branches by thwarting presidential nominations.

The “nuclear option” — a prerogative that lets a simple majority of senators change the rules — had to be back on the table. Reid had threatened it many times in the face of Republican obstruction but always walked back from the precipice. But after the Hagel vote, he initiated a new whip count and started making calls to his members.

“Reid understood at that point that the culture of the Republican Party and the mindset wouldn’t change,” said a Democratic leadership aide close to Reid. “It’s purely about politics for them. And it’s very difficult to come to a negotiated agreement with people who aren’t interested in the merits of the conversation. They just want to oppose the president and show their base they’re opposing the president.”

Even though the proposed change would not do away with the filibuster completely — it would only apply to executive and judicial nominees except the Supreme Court — it was not going to be an easy lift. Democrats needed at least 51 of their 55 senators, and many senior members were uneasy with ending the 60-vote threshold. But Reid would get help from true believers inside and outside the Senate — and from Republicans whose obstruction would make the case for change self-evident.

***

Sen. Jeff Merkley, a Democrat from Oregon who was elected in the Democratic sweep with Obama in 2008, had made filibuster reform his personal mission. Staffers in his office kept a list of Democratic senators who were sour on the nuclear option and needed to be persuaded: Patrick Leahy of Vermont, Barbara Boxer of California, Dianne Feinstein of California, Mark Pryor of Arkansas, Max Baucus of Montana, Jack Reed of Rhode Island and Carl Levin of Michigan.

Merkley sprang into action after the Hagel filibuster. Outside pro-reform groups — especially Fix The Senate Now, a large coalition of liberal organizations and labor unions whose agendas had been stymied by the filibuster — reignited their push. Fix The Senate’s members flooded senators’ offices with calls demanding a rules change.

Three weeks later, in early March, Republicans filibustered Caitlin Halligan, Obama nominee to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Halligan is a respected and accomplished lawyer who argued cases before the Supreme Court. Republicans complained that Halligan had defended a state gun control law while serving as solicitor general of New York, which critics said amounted to attacking her for doing her job. The White House soon withdrew her nomination. Republicans were working wonders for the filibuster-reform cause.

“Republicans hid behind a cloture vote — a filibuster by another term — to prevent a simple up or down vote on this important nomination,” said a livid Reid. The Senate, he lamented, had devolved into a place where “a small minority obstructs from behind closed doors, without ever coming to the Senate floor.”

Reid and Merkley had been at odds since January, when Merkley felt betrayed by the Democratic leader’s decision to thwart reform in favor of a handshake deal with Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader, that preserved the filibuster. Within days of the Halligan filibuster, the two senators mended fences. GOP obstructionism had shown Reid that Merkley was right. The two pledged to work together this time and hatched a plan to end the gridlock on nominations, come what may.

The plan had three steps: First, they would separately bring up a series of high-profile nominations to draw attention to Republicans’ obstruction. Second, they would make the case for the nuclear option privately to skeptical senators. Finally, they would enlist outside allies like Fix The Senate to build grassroots support. They did not just have to convince the Democrats that the Senate was broken. They also had to convince them that they had a responsibility to get it working again.

They quickly refocused Merkley’s list. They always believed Levin was a lost cause — he had long been an outspoken defender of the filibuster. One of his former aides, Rich Arenberg, had actually written a book extolling its virtues as the “soul of the Senate.” The rest were not going to be easy sells. Leahy and Feinstein were old bulls wary of upending tradition. Boxer was worried about a possible future Republican-controlled Senate weakening abortion rights. Pryor and Baucus were up for re-election in red states. But Reid and Merkley thought each of them was persuadable.

Merkley circulated memos to colleagues making the case: he explained how the filibuster has weakened over time and how majorities have changed various rules on many occasions with a bare majority. He told colleagues filibuster reform was inevitable unless their party unilaterally surrendered once they returned to the minority. A Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, he insisted, would scrap the filibuster in a heartbeat.

The Short List: Democratic Senator Jeff Merkley (front, center) kept a list of senators who were sour on the nuclear option and needed to be persuaded. It included (from left to right) Carl Levin (D-MI), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Max Baucus (D-MT) and Jack Reed (D-RI). Credits: AP/J. Scott Applewhite/Manuel Balce Ceneta. TPM photo illustration by Christopher O’Driscoll.

The thing to understand about the filibuster is that while it is a long-running tradition, it came about by way of historical accident. Unbeknownst to many, the minority stalling tactic is not protected by the Constitution and has been weakened over time by majorities in responses to abuses by minorities.

In 1805, Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel and, upon tendering his resignation from the vice presidency, persuaded senators to take up some changes to the rules. One of Burr’s changes, leaders soon realized, had unintentionally stripped their ability to cut off debate, or achieve “cloture.” A single senator could obstruct and delay business indefinitely.

At first, the filibuster was not a problem because it was almost never used for about a century. Then, a small minority of senators started running out the clock toward the end of congressional sessions. In 1917, the majority retaliated by changed the rules and set the “cloture” threshold at 67 senators.

In the middle of the 20th century, when civil rights legislation was moving through Congress, opponents escalated their use of the filibuster. South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond, then a Democrat, held the record for the longest filibuster in history when he spoke for 24 hours and 18 minutes to stall the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

In 1975, a frustrated majority again changed the rules, this time lowering the cloture threshold to 60 senators, where it had remained ever since.

The modern abuse of the filibuster — what ultimately forced Reid and Merkley into action — can be traced back to the 1990s after Republicans took over Congress, or perhaps to the 2000s, when Democrats mounted serial filibusters of George W. Bush’s nominees to the D.C. Circuit Court and other appeals courts whom they labeled ideologically extreme. It has since been an arms race, and the McConnell-led Senate minority has escalated it to startling new heights.

Unlike ever before, 60 votes became the norm to move any legislation or nominee through the Senate. The Republican minority in the 111th Congress and onward would object to straight up-or-down votes as a matter or course. Sometimes they would use the filibuster as leverage to negotiate debate time and amendments with the majority. Other times they would refuse to budge and block business entirely.

***

Early in the spring of 2013, Republicans threatened to filibuster a series of Obama’s nominations to lead executive agencies including the National Labor Relations Board (NRLB), Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Republicans did not exactly object to the nominees; they simply did not want the agencies — which they perceived as pro-labor, pro-consumer and pro-environment — to function properly. Critics fumed that Republicans were using the filibuster to effectively invalidate the law.

By early April, Reid was openly threatening to use the nuclear option again, warning “all within the sound of my voice” that a simple majority could change the rules on any given day. “And I will do that if necessary.”

The CFBP was leaderless. The NLRB was already crippled by Senate Republicans blocking Obama nominees and by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals — itself a central focus of the filibuster battle — ruling that Obama’s recess appointments to the board were unconstitutional. Labor unions were freaking out and putting the screws to Democrats to act. Their message was breaking through.

“Despite the agreement we reached in January, Republican obstruction on nominees continues unabated,” Reid said in late May. “I want to make the Senate work again.”

His qualms were well grounded: a nonpartisan congressional report had just found that Obama’s nominees were facing more obstruction and delays than any of the previous five presidents.

It was simply a matter of getting the votes. “If he were allowed to make the decision himself, he would definitely do it,” an aide familiar with Reid’s thinking said at the time.

McConnell was furious. “These continued threats to use the nuclear option point to the majority’s own culture of intimidation here in the Senate,” he said. “Their view is that you had better confirm the people we want, when we want them, or we’ll break the rules of the Senate to change the rules so you can’t stop us. So much for respecting the rights of the minority.”

The drumbeat was growing louder, but suddenly on May 23 Reid hit pause on the plan he formed with Merkley so the Senate could pass immigration reform. “I’m not going to do anything to interfere with the immigration bill,” he said just before the vote. The Senate passed the bill in a 68-to-32 vote, capturing some Republicans.

***

Days later, Reid executed the first step. He filed cloture on seven nominations: Richard Cordray for CFPB, Gina McCarthy for EPA, Tom Perez for Labor, Fred Hochberg for the Export-Import Bank and three picks for the NLRB. Perez, McCarthy and Hochberg had the votes. The battle was actually about the NLRB and CFPB picks, but Reid wanted to stack them all up together to make a point.

McConnell called it an “absolutely phony, manufactured crisis” and warned Reid he would “be remembered as the worst leader in the Senate, ever” if he triggered the nuclear option. “No majority leader wants written on his tombstone that he presided over the end of the Senate. If this majority leader caves to the fringes and lets this happen, I’m afraid that’s exactly what they’ll write,” he said.

McConnell stepped up his game, vowing that if Reid were to nuke the filibuster for executive nominations, Republicans would nuke the filibuster for everything, including legislation.

“There not a doubt in my mind that if the majority breaks the rules of the Senate to change the rules of the Senate with regard to nominations, the next majority will do it for everything,” McConnell said on the floor. “I wouldn’t be able to argue, a year and a half from now if I were the majority leader, to my colleagues that we shouldn’t enact our legislative agenda with a simple 51 votes, having seen what the previous majority just did.”

McConnell’s threat made Democrats nervous. In just a few years, the filibuster could conceivably be the only thing stopping Republicans from turning America into a tea party utopia. Did Democrats really want to give that up?

Reid and Merkley sought to ease their minds. “Merkley was making the argument strenuously within the caucus that there’s no doubt that if Republicans took over, they would change the rules,” said a pro-reform Senate aide. For the time being, Democrats were placated.

The Maverick: Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) quietly came to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) with a proposition: if he brought Reid enough votes to confirm those nominees, would he refrain from a rules change? Credit: AP/Charles Dharapak.

Reid scheduled the seven votes for Tuesday, July 16. He then paid a visit to the White House to give them a heads-up. I am going nuclear, Reid told the president. I will support you, Obama responded. And at the GOP’s request, he set up a rare all-senators meeting the night before in the Old Senate Chamber. It turned out to be a colossal waste of time.

Meanwhile, Sen. John McCain, an Arizona Republican who occasionally lives up to his maverick reputation, quietly came to Reid’s office with a proposition: if he brought Reid enough votes to confirm those nominees, would he refrain from a rules change? Reid listened. He enlisted his ally, Chuck Schumer of New York, to help hash out an agreement with McCain. The terms were clear: all the nominations must go through and we won’t take the nuclear option off the table in the future. I can work with that, McCain said.

The day before the votes, McConnell also came to Reid’s office seeking to cut a deal to defuse the standoff. Reid brushed him aside because McCain was offering more. Say what you want, I have the votes to change the filibuster, the Democratic leader told his counterpart. McConnell had been undercut.

Meanwhile, Reid faced a setback that nearly derailed his filibuster reform plan. Sen. Joe Manchin, Democrat of West Virginia, once favorable to filibuster reform, had switched sides. Reform advocates were worried he’d take more Democratic votes with him and extinguish Reid’s nuclear option threat.

“We initially had Manchin in the ‘good’ category, but as we got closer he got squirrelly and untrustworthy about it,” says an outside pro-reform source involved in the fight. “Just before or during the Old Senate Chamber meeting, he mentioned to Reid that he wasn’t with him. When he came out of that, he started telling folks, ‘I’m not with Harry.’ It totally blew everything up… It made us go back and start recounting numbers. The question was, if Manchin went south would he have taken some votes with him?” It turned out that no, he would not.

The Reid-McCain deal was finalized moments before the votes began. A cohort of GOP senators agreed to supply the votes to get to 60 so Democrats could move forward and confirm the seven nominees. The only catch: Democrats would replace two recess-appointed NLRB nominees with others. Obama replaced Sharon Block and Richard Griffin with Nancy Schiffer, an AFL-CIO labor lawyer, and Kent Hirozawa, a former counsel to National Labor Relations Board Chairman Pearce.

“Everything for nothing,” gloated an aide close to Reid. “This confrontation was always set up in such a way that the Republicans chose their own adventure — if they wanted to meet all our requirements, then there was no nuclear option.”

***

Three months later, after the government shutdown fiasco, Reid moved to fill vacancies on the D.C. Circuit. Widely seen as the second most powerful federal court, it was a gateway to Obama’s second-term agenda as it tended to have the final say on matters of executive authority.

Back in May, Republicans had acquiesced to filling one vacancy — the one Halligan had originally been nominated for — with Sri Srinivasan, an Obama nominee with such broad support that even arch-conservative Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Mike Lee of Utah heaped praise on him. But there were three more vacancies that Democrats were determined to fill and Republicans, as early as August, laid the groundwork for a mass filibuster of all three. They said the court had a low caseload and didn’t need more judges, to which Democrats retorted that they were happy to fill the vacant seats under a Republican president.

In reality, Republicans knew the court was their silent weapon against Obama. It leaned conservative, and had overturned a slew of Obama’s regulations on health care, environmental protection, labor and financial reform. Filling the vacancies could make the court more Obama-friendly.

“There is no reason to upset the current makeup of the court, particularly when the reason for doing so appears to be ideologically driven,” said Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA), who introduced a bill to reduce the size of the court by — conveniently — three judges.

This time Reid played his cards close to the vest. No grandstanding, no threats. He would bring up Obama’s three nominees — Patricia Millett, Cornelia Pillard and Robert Wilkens — one at a time, and if Republicans filibustered, he would move to change the rules. He had secured 51 votes for executive branch nominees, but judges were a heavier lift. They were lifetime-tenured, and some progressives, primarily abortion-rights activists, wanted to protect the filibuster for judges.

Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, the No. 2 Republican in the Senate, said he did not “really take this threat of the nuclear option very seriously” on judicial nominations, perhaps not realizing the damage Republican stalling tactics had done.

The GOP Players: (From left to right) Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN), Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) all opposed filibuster reform and the nuclear option. Credits: AP/Cliff Owen/J. Scott Applewhite. TPM photo illustration by Christopher O’Driscoll.

Reid plotted to hold each vote one week apart to draw attention to the filibusters. First Millett was blocked, without regard to her qualifications, and that swayed a number of old-school Democrats. Then Pillard was blocked, and that was the last straw for Judiciary Chairman Leahy, longtime opponent of the nuclear option, who suddenly seemed open to changing the rules.

“I think we’re at the point where there will have to be a rules change,” the senator told reporters.

Filibuster reformers were thrilled. “When Leahy made his comment, we all immediately perked up,” said Shane Larsen, the legislative director of the Communications Workers of America, a labor union at the forefront of the pro-reform movement. “That’s when we all started to think, wow, this is serious. Leahy has always been — I don’t want to say opposed — but was always cautious. So for him to be publicly calling for this — really led us to think, this is a big deal.”

Republicans continued to laugh off the idea that Democrats carry through with the change. They correctly pointed out that Reid had led the Democrats to serial filibusters of George W. Bush’s judicial nominees just a few years earlier. At the time, he hailed the filibuster in moralistic terms. The hypocrisy was evident, even if the situations were different.

“If you’re going to bring up the nuclear threat every time something comes up, people say, ‘Bring it on.’ Go ahead. Go ahead,” said Sen. Bob Corker, Republican of Tennessee, outright baiting Reid. “I mean, if that’s what you want to do, do it. I don’t think they will.”

The Republicans underestimated Reid and did not realize how far they had overplayed their hand. He was quiet in public but aggressively working over his colleagues in private. He did not want any “gangs” to spring up to avoid the rules change. He was making phone calls, speaking with them in person and pressing the case for a rules change to scrap the filibuster for executive and non-Supreme Court judicial nominees. It was about preventing the Senate from becoming obsolete, he told them. It was about making sure government could carry out its most basic functions.

Democratic leaders were circulating polls showing that the public mostly does not care what the Senate rules are. They circulated a chart showing that of the 168 filibusters of presidential nominees in U.S. history, a whopping 82 had occurred under Obama.

“Leahy quickly came around. His statements were incredibly helpful,” said a Democratic leadership aide close to Reid. “Reid was making calls and talking to members, personally, to convince themselves of the rightness of the cause. Obviously [Dick] Durbin and Schumer were helping as well. A lot of the conversations were private.”

The third GOP filibuster, of Wilkens, was inevitable. The following day, Reid had secured the votes. It was a done deal.

As she was walking into a Democratic caucus meeting to make her case, Feinstein, one of the last holdouts, told TPM she had come around to support the nuclear option.

Feinstein said that “it is unconscionable for a president not to be able to have his cabinet team, his sub-cabinet team and not be able to appoint judges.” She had hoped the filibuster agreement over the summer would lead to a “new day” in the Senate, but “the new day lasted one week,” she said. “And then we’re back to the usual politics.”

Boxer, too, had been convinced. “I think any president, Democratic or Republican, deserves to have a team in place,” she said. “And I really think that when you don’t appoint judges, justice delayed is justice denied.”

Of the holdouts, Levin still would not budge. “If the majority can change the rules,” he warned, “there are no rules.” But his vote did not matter; Reid had enough votes without him.

In the Capitol, a reporter haplessly tried to corner Reid. “Why don’t you force Republicans to do talking filibusters?” the reporter asked. “And what would that accomplish?” Reid said. The reporter shrugged. “Yeah, that’s right,” Reid said, mocking the reporter’s shrug.

***

Blocked: The initial nominations of (from left to right) Chuck Hagel, Caitlin Halligan, Nina Pillard and Patricia Millett were all blocked by filibusters in the Senate. Credits: AP/Manuel Balce Ceneta. TPM photo illustration by Christopher O’Driscoll.

A few days left before a two-week Thanksgiving recess, Reid was ready to execute his plan. Senators were put on alert the morning of Thursday, Nov. 21.

The majority leader delivered a barn-burner of a speech on the Senate floor making his case for the nuclear option. “It’s time to change the Senate before this institution becomes obsolete,” he declared. “Is the Senate working now? Can anyone say the Senate is working now? I don’t think so.”

Conservatives were caught off guard. Heritage Action, the activist group, scrambled to warn senators not to assist Reid with changing the rules — but it did not matter. Republicans had already given Reid all the help he needed by blocking the nominees. McConnell scurried to the floor to make his case against Reid. He accused the Democrats of trying to change the subject from Obamacare’s rollout woes and “cook up some fake fight over judges,” insisting that “by any objective standard, Senate Republicans have been very, very fair to this president” on nominations.

“I say to my friends on the other side of the aisle: you’ll regret this,” McConnell warned. “And you may regret it a lot sooner than you think.”

Everything went according to plan. Reid brought up the Millett nomination again to give Republicans one last chance. They filibustered her again. Then he called for a simple-majority vote to invoke cloture on the nomination. Reid had done it. He would hit the nuclear button. The presiding officer — erstwhile filibuster defender Leahy — ruled it out of order, and a vote took place on whether to uphold the ruling. Fifty-two Democrats voted with Reid to overturn it, setting a new precedent by which a simple majority could cut off debate on executive branch and non-Supreme Court judicial nominees.

Within moments, the Senate, for the first time in U.S. history, advanced a presidential nomination with fewer than 60 votes: the Millett nomination moved forward by a vote of 55-43. She was officially confirmed on Dec. 10, when the Senate reconvened after Thanksgiving break, in a 56-38 vote.

“This is a great day for the U.S. Senate,” a very happy Jeff Merkley told TPM a few hours after the rules change. “It’s a great day for the American people.”

***

Filibuster proponents were despondent. They knew Reid had just struck the dagger into the heart of the filibuster. The only norm holding it together — not to change it with 51 votes — had just died.

“In my view, the majority having now established the precedent that a majority can at any time change any rule makes it near inevitable that the filibuster will be eliminated in the Senate,” said Arenberg, the former Levin aide and author of a pro-filibuster book.

In the end, just three Democrats voted against going nuclear: Carl Levin, Mark Pryor and Joe Manchin.

“Frankly,” Reid said a few days later, “if I needed a couple of those, I could’ve gotten those, too.”

So, were Republicans really caught off guard or did they secretly want Reid to pull the trigger?

Norm Ornstein, a centrist scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, speculated that McConnell purposefully goaded Reid into changing the rules so he would have a pretext to kill the filibuster entirely if Republicans win control of the Senate next year. “It was a set of actions begging for a return nuclear response,” Ornstein says.

But the view that McConnell as majority leader would change the rules anyway gradually hardened into conventional wisdom among Democratic senators and aides. And it helped sway the skeptics.

Moments after the vote, TPM asked Reid if he worried about a Majority Leader McConnell killing the filibuster entirely.

“Let him do it,” Reid said. “Why in the world would we care?”