ORLANDO, Florida — Desmond Meade doesn’t want to talk about Florida Governor Rick Scott. Nor does he want to talk about partisan politics or racial sentencing disparities. Most of all, he doesn’t want to talk about himself.

That might seem odd for the head of a group devoted to restoring the franchise to 1.4 million Floridians with felony convictions, whose voting rights are automatically stripped under a Scott administration policy.

But that’s the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition’s goal: complicating the public understanding of who is affected by felon disenfranchisement, and who enforces these policies. For the FRRC, it’s not a question of Republicans trying to suppress Democratic votes or the stain of the Deep South’s Jim Crow legacy or arguments over being weak on crime. Their focus, they say, is on basic civil rights.

This approach seems to be working. As part of a coalition of groups operating under the banner Second Chances Florida, the FRRC helped gather over 1 million signatures to get a constitutional amendment to change this policy on the November ballot. The proposal, which would not apply to those convicted of murder or felony sexual offenses, was unanimously approved by the state Supreme Court. And months of polling shows the measure consistently winning more than the 60 percent support it needs to pass.

Most strikingly, this effort was carried out with no real organized, well-funded opposition trying to kill it.

Over lunch at an Orlando wing spot on a sticky September afternoon, Meade said that their effort, which was years in the making, only gathered momentum recently thanks to “a false narrative that has been perpetuated on both sides.”

“It has created an illusion of who is impacted by the criminal justice system,” Meade, a heavyset 52-year-old who opens his eyes wide when emphasizing a point, said. “It has recklessly tied a human rights situation to partisan politics.”

“We’re talking about the concept of forgiveness,” he continued. “We all want to be forgiven at some point in our lives. So we can easily relate to: when a debt is paid, it’s paid. It’s partisan politics that creates us against them. But if we’re just dealing along the lines of forgiveness, it’s all of us.”

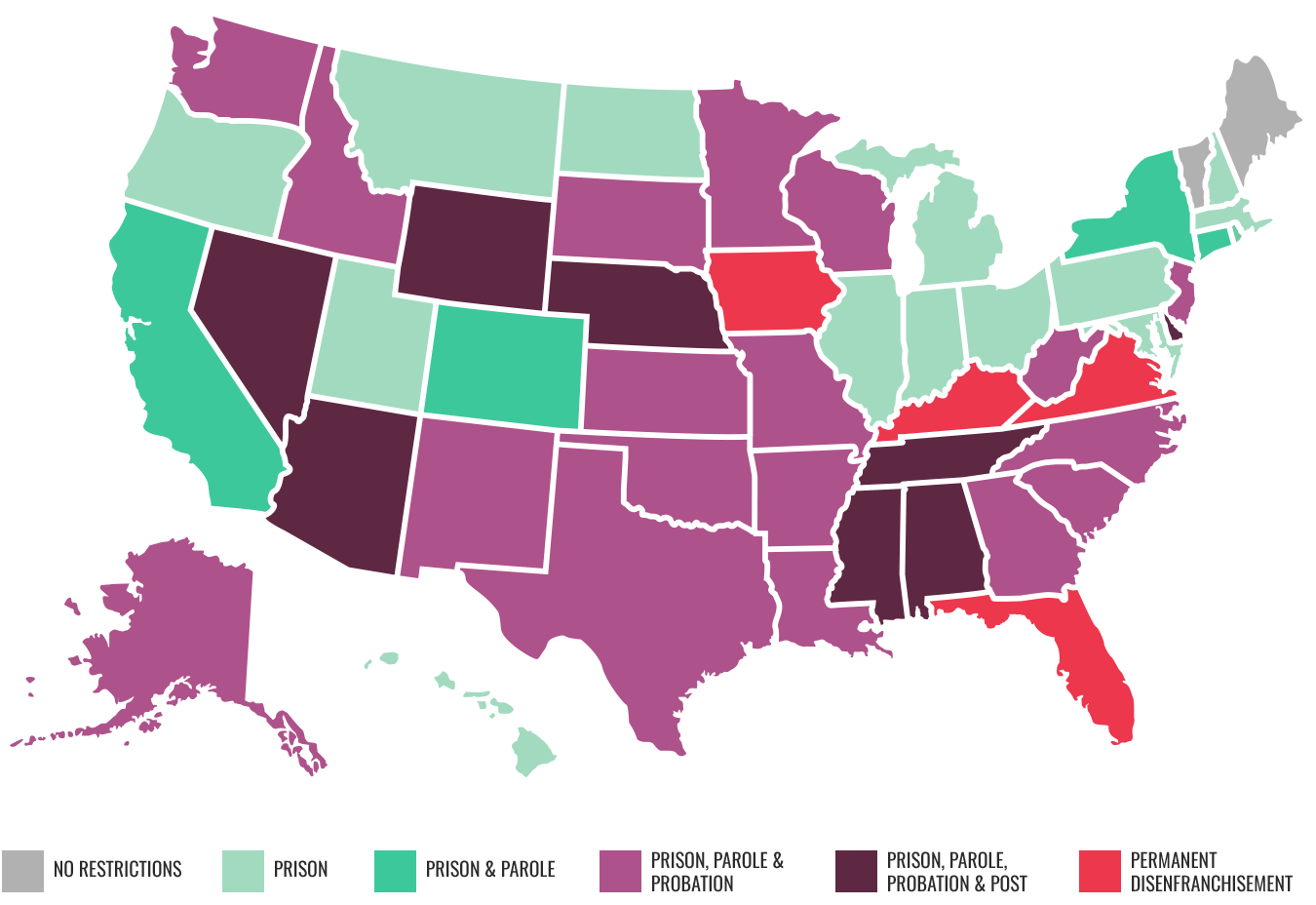

Different states take wildly varied approaches to this question. In, say, Delaware people with most types of felony convictions have their voting rights automatically restored after completing prison, probation, and parole. In Pennsylvania, those on parole or probation can vote. Vermont, Maine, and jurisdictions like Cooks County, Illinois allow people to cast ballots from jail.

Florida is one of four states with a constitution that permanently disenfranchises residents with past felony convictions. But how that policy is enforced is up to interpretation.

Florida’s governor oversees the state clemency board, which is rounded out by three members of the Cabinet: the chief financial officer, attorney general, and agricultural commissioner.

When Gov. Charlie Crist, then a Republican, took office in 2007, he convinced the board to streamline the clemency process, allowing non-violent felons to get their rights back without hearings. Over 150,000 clemencies were granted in just four years.

In 2011, Scott and his new Cabinet unanimously voted, after 30 minutes of public debate, to change those rules. Any Floridian convicted of a felony must now wait at least five years after completing their sentences — including parole or probation and paying off any fines — to apply for the opportunity to come before the board and make a “pitch” to get their voting rights back. Roughly 3,000 people have had their rights restored in the past eight years, and the state has a backlog of over 10,000 cases.

The Scott administration claims that this case-by-case approach is necessary to prevent the swift restoration of voting rights to those undeserving of that privilege.

Both the FRRC campaign and the plaintiffs in Hand v. Scott, a federal lawsuit currently winding its way through the courts, disagree. Though these efforts are separate, their arguments are similar: rights restoration should be an automatic, evenly applied process not left up to the whim of four elected officials or a change in administration. Formerly incarcerated people don’t want a free pass, they want to be able to participate in the political system that has indelibly shaped their lives.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals will likely not issue a final decision in the federal lawsuit until after the November midterms. But in just a few weeks, when voters go to the polls, they could pass an amendment with the potential to transform the state’s politics.

Amendment 4 would have a dramatic impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of disenfranchised Floridians, and on who gets voted into office in a state with razor-thin electoral margins.

A wide spectrum of interests support a swifter path to rights restoration in Florida: civil rights groups like the Brennan Center and American Civil Liberties Union, the sheriff of conservative Dixie County, a handful of Florida Republican lawmakers, church leaders, and the American Probation and Parole Association, a trade group representing people who work on parole-related issues. And while opposition to changing the law exists, that, too, doesn’t fall perfectly along partisan lines: The Koch brothers’ Freedom Partners recently threw its support behind Amendment 4, saying it “will make our society safer, our system more just.”

Race is at the historical root of measures intended to restrict access to the ballot box in the United States. During Reconstruction, and the years that followed, cities and states experimented with ballot box-stuffing, poll taxes and literacy tests to prevent newly freed slaves from voting. Another tool: expanding the range of crimes that led to disenfranchisement.

In the case of Cuifie Washington, a black Ocala, Florida man barred from voting in the 1880 congressional elections, that crime was stealing three oranges, Middle Tennessee State University professor Pippa Holloway writes in her book, “Living In Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship.”

“For white Democrats seeking to regain political power in the South after Reconstruction, these events in Florida demonstrated the success of a new scheme to disfranchise African Americans: denying the vote to individuals convicted of certain criminal acts,” Holloway writes. “Between 1874 and 1882 a number of southern states amended their constitutions and revised their laws to disfranchise for petty theft as part of a larger effort to disfranchise African American voters.”

Enslaved people and former criminals occupied a similar legal status at the time, Holloway explained in a phone interview.

“Both populations lost or didn’t have legal rights, citizenship rights, and so on,” Holloway said. “There was this idea after the Civil War that they could actually turn newly freed slaves back into degraded individuals through this process of criminalization.”

The Jim Crow era that began at the end of reconstruction and continued into the 20th Century brought a new wave of policies stripping those with felony convictions of voting rights, according to Michael McDonald, an expert in U.S. elections at the University of Florida.

“Even though it’s not explicitly in the legislative record in many cases that a particular group was being targeted, they clearly had that intent,” McDonald said. “But there’s not much in legal record to support that, which makes it very difficult to challenge these laws under the Voting Rights Act.”

Florida’s current clemency policy was instituted a few years after Jim Crow ended, as part of the revised 1968 state Constitution. Under the administration of the fiercely pro-segregation, pro-capital punishment Republican governor Claude R. Kirk, the power to grant clemency and restore voting rights to former felons was vested in the hands of “the Governor and members of the Cabinet.” Under the state’s rules, “the Governor has the unfettered discretion to deny clemency at any time, for any reason.”

The war on drugs caused the nation’s population of disenfranchised felons to swell, Middle Tennessee State University’s Holloway said.

“What happened in the second half of the 20th century was inspired by the 1870s and 80s,” Holloway said. “They lower the bar. Even for minor larceny, small crack possession, you lose the right to vote. And that’s what’s new.”

“When mass incarceration happened, mass disenfranchisement happened,” Holloway added.

The numbers tell the story. In 1976, there were 1.17 million disenfranchised felons in the U.S. As of 2016, that number had grown to 6.1 million.

A “stunning” 48 percent of the country’s disenfranchised felons, who have completed all aspects of their post-conviction punishment, live in Florida, according to the Sentencing Project — the state has more than 500 specific felony crimes on the books. More than one in five black Floridians cannot vote.

Opponents of restructuring Florida’s clemency process acknowledge the racial disparities inherent in the system, but say that the heart of their arguments rest elsewhere. What most concerns them is taking a blanket approach to reform.

The D.C. area-based Center for Equal Opportunity, which bills itself as the “nation’s only conservative think tank devoted to issues of race and ethnicity,” filed an amicus brief on behalf of the state in the Hand v. Scott lawsuit.

“We think that when you are not willing to follow the law yourself, you can’t claim the right to make the law for everyone else,” the group’s president, Roger Clegg, told TPM in a phone call. “And that’s what you do when you vote. And therefore it makes sense for felons who lose their right to vote until they’ve shown that they’ve turned over a new leaf.”

Tampa attorney Richard Harrison agrees that voting rights should be restored “on a case by case basis.” Though he has no involvement in the federal lawsuit, Harrison is the force behind Floridians for a Sensible Voting Rights Policy, the only group founded to block Amendment 4.

“Most felons are felons for a reason; the reason being they’re not very good people,” he told TPM in a phone interview. “Do I think they all suddenly change and become good people? No. So, convince us that you’ve changed your life around? The state should be there to help you. But we’re not going to grant clemency to a million and a half people and hope that it turns out that we were right.”

Conceding that the current system “has the potential to be arbitrary,” Harrison said that violent felons should face a harder road to getting their civil rights back than, say, non-violent first-time offenders.

Scott administration press secretary Ashley Cook echoed those arguments in a statement to TPM: “The Governor believes that people who have been convicted of felony offenses including crimes like murder, violence against children and domestic violence, should demonstrate that they can live a life free of crime while being accountable to our communities.”

All of these actors claim that the subjectivity baked into Florida’s current system is one of the strongest arguments in its favor.

Brett Ramsden is representative of Florida’s more than 1 million disenfranchised. Like the majority of those individuals, his offenses were drug-related. And though the state’s system disproportionately affects African-Americans, the majority of Floridians who cannot vote because of a felony conviction are, like Ramsden, white.

Ramsden grew up in the small central West Coast town of Palmetto, earning straight As and playing as a star pitcher on his high school baseball team. His hometown happens to sit at the crossroads between Miami and Tampa, ground zero of the country’s main drug trafficking corridor for opioids.

By senior year of high school, Ramsden’s casual partying had turned into something else. His grades had slipped. His friends went off to college. Stuck in Palmetto, waking up every day unable to “see past a few hours ahead, the afternoon,” Ramsden started experimenting with oxycodone. The drug fueled a 15-year binge of abuse and stealing to fuel the habit. That period, Ramsden recounted, saw him sentenced to six months at a treatment center for stealing jewelry from a friend’s mother; doing oxy on the day of the funeral of a friend who overdosed; experimenting with drugs he “never thought” he’d be doing like crack and heroin.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2013, when Ramsden was arrested on eight felony charges for stealing items he could resell from stores like Dick’s Sporting Goods and Walmart, that the rampage stopped.

Now married with a teething, one-year-old daughter, whose wails were audible over the phone, Ramsden works with both the FRRC and the Christian Coalition. He told TPM that people he met through recovery pushed him to publicly share his story of everyday devastation — and the road back from it. Ramsden is one of many recovering addicts and former felons to cite his faith for helping him get back on track, and having children as the driving motivator for restoring his voting rights.

As Ramsden acknowledges, his story is also one of astonishing racial privilege. He described two consecutive weekends in his senior year in which he “should have been arrested for DUIs” but got off after his parents and the cops came to an agreement. Nor was Ramsden ever jailed for his felony charges. A state attorney accepted his family’s proposal to send him to a treatment center in Naples, where he spent a year in recovery. Though Ramsden was stripped of his civil rights, he served no time and paid no court costs or costs of supervision.

Contrast that with the experience of David Ayala, a black Puerto Rican Brooklyn native who described himself as “a product of the school to prison pipeline.” Sipping coffee at a Starbucks in an Orlando strip mall, Ayala, now an organizer with Latino Justice, recalled receiving his first conviction at age 12 on drug possession charges after escaping from a group home. Until age 33, he was in and out of juvenile detention centers, Riker’s Island, state prison in New York, and, finally, a federal prison in central Florida — all for drug-related offenses.

After his release in 2006, Ayala managed to get a job as a trainer at an LA Fitness and met the woman who later became his wife. He got his GED, went to college, had two girls, and became a business account manager at Sprint.

Politics never much interested him, and he’d always assumed he could vote since his convictions were filed in Pennsylvania and New York. It wasn’t until 2016 that he learned Florida did not grant him that right. Ayala found himself unable to cast a ballot in the most important race he’d ever been a part of: his wife Aramis’ ultimately successful run for state attorney.

“I was involved with her campaign, organizing, knocking on doors, phone banking, doing everything I can to help her get elected,” Ayala said. “But I wasn’t going to be able to do the one most important thing you can do for your candidate, which is vote for her.”

“Some day my daughters are gonna ask me why I wasn’t able to vote for mommy and I’m going to have to explain it,” he went on. “Those are the things that haunt me.”

[ Read more about David Ayala. (Prime access.) ]

The Florida clemency board meets four times a year at the State Capitol Building in Tallahassee. At the front of a large, wood-paneled room, the board — currently composed of Scott, Attorney General Pam Bondi, Agricultural Commissioner Adam Putnam, and state CFO Jimmy Patronis — sits in black leather chairs at a semi-circular table flanked by American flags.

Over the course of four hours, the board hears from between 50 and 75 Floridians, many of whom have taken off work, driven hours across the state, or hired lawyers to vouch for them at their hearing. About half of the petitioners will have their voting rights restored.

Scott typically opens the hearing by reiterating that “clemency is an act of mercy” to which petitioners have “no right or guarantee.”

One by one, sometimes with family members at their side, they are called to the front of the room to share their stories and respond to a barrage of inquiries about their personal lives. When was the last time you had a drink? How often do you do so? How many speeding tickets have you received since your release? Are you a proud mom? Have you seen your husband act violently?

Patronis, in particular, is fond of asking petitioners about their church attendance. His office did not respond to TPM’s request for comment on a notable incident from a mid-June hearing in which he asked a black petitioner, Erwin Jones, how many children he had — and “how many different mothers to those children?”

The board has restored the rights of some petitioners who said they continued to drink socially after serving time for DUI manslaughter convictions; it has denied the rights to others. Traffic violations are frequently cited in rejecting petitioners’ applications for the restoration of civil rights.

For the lucky few whose rights are restored, Scott and Bondi sometimes pose for photographs or sign autographs.

Frequently, petitioners try to play to the board’s political leanings. A woman at a June 2015 hearing testified to the “conservative principles” of her formerly incarcerated husband; a petitioner in March 2018 praised Bondi’s recent appearance on Fox News.

In one infamous example from 2013, Scott asked ex-felon Steven Warner about a vote he illegally cast in the 2010 election, before his rights had been restored.

“Actually, I voted for you,” Warner replied.

Scott laughed. Within seconds, the board moved to restore Warner’s civil rights.

These kind of exchanges are detailed at length in the Fair Election Legal Network’s 2017 Hand v. Scott lawsuit, which criticizes the administration’s “haphazard and arbitrary” system of reinfranchisement.

U.S. District Judge Mark Walker in February found that the process granted the board “unfettered discretion” and violated the First Amendment. In March, he issued an injunction ordering the clemency board to craft a new system by April 26 that relies on more than their “whims, passing emotions, or perceptions.”

The Scott administration appealed Walker’s ruling to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, which blocked it. Oral arguments in the case are complete, and each side is now waiting on a decision on the appeal from the court’s three-judge panel.

In a phone interview with TPM, Michelle Kanter Cohen, one of the plaintiffs’ lead attorneys, said that the lawsuit was about ensuring that “uniform and neutral criteria” are used to restore voting rights. Kanter Cohen also brought up a commonly cited benefit of restoring voting rights: reducing recidivism.

“In terms of bringing people back into society, the right to vote is very much part of that,” she said. “If people feel that they are full citizens and they are invested in their community, they’re less likely to have a recidivism problem.”

Several studies have shown a positive relationship between prosocial behaviors like voting and lower recidivism rates, including a report released earlier this year by the Republican-leaning Washington Economics Group of Coral Gables, Florida. The report, which compared data from the Crist administration to current data, found that Florida “lost an estimated $385 million a year in economic impact, spent millions on court and prison costs, had 3,500 more offenders return to prison, and lost the opportunity to create about 3,800 new jobs,” as the Tampa Bay Times summarized it.

Stripping voting rights is an “extension of the sentence” for people with criminal histories, who are expected to comply with other citizenship requirements like paying taxes, argued the Sentencing Project’s director of advocacy, Nicole Porter.

That’s the experience of Yraida Guanipa, a Miami consultant, mother of two and defendant in the federal lawsuit who was released from prison in 2006 after serving 10-and-a-half years on drug-related charges.

“It’s a punishment beyond the punishments,” Guanipa, who is not yet eligible to apply for clemency under the current policy, told TPM.

Guanipa said she wants a “voice” in the political process because her experience with the criminal justice system showed her that elected officials “don’t know what we go through.”

“They don’t understand what 15 years of incarceration means to a human being as a nonviolent, first-time offender,” Guanipa said. “Most people making the laws are people who were born with money, raised with money and privilege, and then live a very privileged life. They don’t have to struggle to pay the daily needs.”

Susanne Manning, now the FRRC’s reentry coordinator, said she too felt like a “second-class citizen” after getting out of jail in 2011. Sitting in a canary-yellow conference room at FRRC’s Orlando offices, Manning, a middle-aged woman with penciled-on eyebrows and keratin-straightened hair, frequently hovered on the verge of tears while recounting the 19 years she spent in prison for embezzling funds from her former employer, a medical manufacturing firm.

“I feel like I have to constantly prove myself over and over,” Manning said. “It’s not enough that I have the pain inside. It’s not enough that I did my sentence. It’s not enough that I’m doing probation. It’s not enough that I’m paying restitution. It’s not enough that I paid my court costs off. It’s not enough that I help people who are getting out of prison and don’t have a place to stay by allowing them in a room in the house that I rent.”

“We’ve been using that phrase around here lately — when a debt is paid, it’s paid,” Manning said of the FRRC’s favorite shorthand for their platform. “But when is it really paid when you’re convicted of a felony in the state of Florida?”

[ Read more about Susanne Manning. (Prime access.) ]

When they go to the polls in November, Floridians will cast ballots on Amendment 4 and on top-of-the-ticket candidates with varying degrees of sympathy for it.

Democratic gubernatorial nominee Andrew Gillum and attorney general nominee Sean Shaw have campaigned hard on their embrace of the proposal, while Sen. Bill Nelson has voiced support for it in his race against Scott.

“You shouldn’t have to come all the way to Tallahassee and appear before the clemency board and explain why you didn’t have a job for six months when you were 45 years old,” Shaw told TPM in a phone interview. “It should be automatic.”

Shaw’s Republican opponent, Ashley Moody, has come out strongly against Amendment 4, while GOP gubernatorial nominee Ron DeSantis has said only that he would “look at” the issue. DeSantis’ spokesperson did not return TPM’s request for comment.

FRRC political director Neil Volz said that these officials’ stances suggest a false partisan divide on this issue. Volz told TPM he received dozens of signups at Trump rallies during the 2016 election by appealing to people’s sense of humanity — reminding them of their neighbors, relatives, and acquaintances who have been caught up in the system.

Volz himself is one of those people. In the mid-2000s, Volz rocked Washington, D.C. when he agreed to testify against lobbyist Jack Abramoff and his former boss, Republican Rep. Bob Ney, in their far-reaching pay-for-play scheme. Abramoff and Ney went to jail for their roles in the corruption scandal.

For agreeing to cooperate, Volz received only probation and community service. But he became a pariah in D.C., and his felony conviction left him with few employment options.

Driving around Orlando in a silver Ford SUV, Volz recalls moving to southwest Florida and working odd jobs at a beach hotel’s shop and mopping floors at a restaurant. He joined Next Level Church and started volunteering at a local homeless coalition, eventually becoming its chairman. He self-published a memoir about the Abramoff scandal and met his now-wife, Pam, an artist.

Volz is warm and unassuming, a large man with black-rimmed glasses and a bristly beard shot through with gray. The floor of his car is scattered with coffee cups from a life spent traveling from conference to speaking engagement; sunglasses hang from the rearview mirror by an American flag-patterned strap.

“I still consider myself a conservative,” Volz said. “I’d register as a Republican if I was able to vote.”

[ Read more about Neil Volz. (Prime access.) ]

For champions of reform, easing the restoration of voting rights is one concern; informing former felons that they’ve regained those rights is another entirely.

Many Americans with felony convictions move between states with different requirements for rights restoration or never learn about the process to apply for clemency, or changes in state law. The fear of being hit with new criminal charges for voting with a felony conviction is acute, particularly given the Trump administration’s zeal for prosecuting voter fraud.

North Carolina, in particular, has enthusiastically pursued charges against some former felons who did not know they were unable to vote. Texas mother Crystal Mason is currently serving a five-year sentence for unintentionally voting illegally while on supervised release for a tax fraud charge.

When states adopt significant policy changes, local governments “need to take responsibility for notifying residents of their right to vote,” the Sentencing Project’s Porter said. “In states where there’s been voter notification for people who were previously excluded or denied their right to register, when state officials send a formal communication to residents, that improved voter participation.”

Not all states are willing to take on this responsibility. In 2017, Alabama passed the Moral Turpitude Act, reducing and clarifying which felonies lead to disenfranchisement.

As part of their years-long lawsuit against Alabama for its unclear felon disenfranchisement policy, the Campaign Legal Center asked that the state engage in due diligence to inform the thousands of affected voters.

But Secretary of State John Merrill (R) explicitly said that he was “not going to spend state resources” informing those individuals that they were no longer disenfranchised — or never were at all.

So the CLC in July teamed up with the Southern Poverty Law Center to carry out that work, going to bus stops, homes, and community events throughout the state to inform Alabamians about the new law and get them registered to vote.

Blair Bowie, a Skadden Foundation Fellow working on the CLC’s campaign, told TPM that “because they have been wrongly told that they cannot vote, the state has a special obligation to correct that misinformation.”

But “we recognized that if the state’s not going to do this public education work, we should go help people on the ground do it themselves,” Bowie added.

[ Read more about what happens when states restore voting rights to former felons. (Prime access.) ]

Some Floridians who’ve been caught up in the criminal justice system see Amendment 4 as an initial — but crucial — step in expanding rights for former felons. Those interviewed by TPM say they take full responsibility for their conduct, but say that the mark on their records has prevented them from moving past it.

At the FRRC’s office, Stefanie Anglin, a bubbly grandmother of two dressed in a stylish black-and-white striped shirt, told TPM that she had to sell her house after a recent separation from her husband.

Because of a 22-year-old conviction for assault and battery with a deadly weapon, she spent three months trying and failing to rent an apartment. Ultimately, Anglin gave up and moved in with her daughter.

“Once Amendment 4 is done, I feel like it’s going to knock down other barriers — like housing, jobs,” Anglin, who now owns her own janitorial company, said. “I haven’t been in trouble in two decades. If that’s not change then I don’t know what is.”

“It starts with voting because that’s what’s going to give us the power,” Anglin continued.

The campaign itself has been empowering for Floridians like Anglin, who said they’ve been cheered by the support they’ve received while gathering signatures and raising awareness at public events. Their stories of neighborly love and bipartisan kindness sound like dispatches from an entirely different America than the one in which we are currently living.

But Amendment 4 supporters want their campaign to be what the FRRC’s Meade called a “shining example” in this grim moment of voter suppression and seemingly unbridgeable policy divides.

“Getting the 1 million or so signatures to get it on the ballot reflects, I think, a desire by the electorate in Florida to right this wrong,” Rep. Charlie Crist, the former Republican governor who now serves in Congress as a Democrat, told TPM in a phone interview. “It’s kind of embarrassing being one of just a few states that still do this. I think we’re a more enlightened place than that. I hope so.”

Allegra Kirkland is a NY-based journalist for TPM

Made possible by