Good news. Global emissions have now flattened for a second year in a row, according to a recent report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) in Paris. The finding is both encouraging and plausible, given the astounding changes taking place in how the world uses energy.

From small domains like Scotland, where booming wind power drove renewables to 57 percent of total electricity generation last year, to big countries like the United States, where coal retirements keep coming, demand growth for fossil fuels has slumped.

To be sure, a vast dependency on coal, natural gas, and oil remains very much embedded in the world’s economic system. But even in China, which built up its own coal position the past two decades, the adoption rate of new wind and solar power has been nothing less than heroic. China, which recently signed on to the Paris agreement, will erect more solar capacity this year (20 GW) than even existed, globally, in 2008.

The news of slowing emissions has also triggered a great deal of excitement that decoupling — the long-held view that economic growth could eventually break free from carbon output — has finally arrived. There is gathering evidence for this optimism. On the energy side of the ledger, energy intensity — a measure of how much energy is required to create GDP — has been in decline in the U.S. for several decades. On the economic side of the ledger, the global economy is increasingly built on digital goods — apps, cloud services, bits, films, data — which require less energy but drive capital nevertheless.

Indeed, if we look at developed regions like Europe, Japan, and North America, emissions peaked back in 2007 and have since been steadily falling. Better still, GDP from these countries, the OECD, has rebounded nicely since the Great Recession, rising from $34 to $39 trillion — this growth has been led by the U.S. So far, so good. However, developed-world countries account for just 25-30 percent of the global population.

Glen Peters, an intrepid Australian a world away from home, is a senior researcher working on the climate problem at The Center for International Climate and Environmental Research—Oslo (CICERO) in Norway. After the IEA released its optimistic report, TPM reached out to Peters for his views. Unsurprisingly, it’s China that’s driving both the optimism, and the uncertainty, over peak emissions.

Image from cicero.com

“Well, the U.S. peaked almost ten years ago. But with China, we’ll probably have to wait five to ten years before we can look back and say, OK, their emissions peaked.” Peters is referring, of course, to the dangers of drawing a baseline that runs back only a year or two, in time. China’s coal consumption trends look great by that measure, remaining flat in 2014, for example. In the same year its oil consumption growth slowed to just 3.3 percent. And for the last two years, China’s use of coal in power generation alone reportedly declined.

The problem, the temptation really, is to declare this brief easing the high summit of energy consumption in China. Draw your baseline back a bit further however—just five years—and coal consumption is up 17 percent between 2009 and 2014. In the same period, oil use is up a fearsome 34 percent. And let’s not forget, even at the present slowdown point, China is still consuming a full half of the world’s coal. In the past decade, China’s coal consumption has gone up a whopping 74 percent.

China’s slower economy, of late, has only added to the puzzle of the country’s future path. “My concern looking ahead,” says Peters, “is the amount of idle coal-fired power capacity that China has at its disposal. If economic growth returned, coal could easily and very quickly increase its share again.”

Celebrating Decoupling

The reason decoupling is such a big deal relates not only to the weight of carbon, but the weight of history. Shortly after Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations in 1776, Britain began to transition away from low-energy wood and biomass to coal. The new energy source was instantly embraced, and a new industrialism thrived on its dense package of transformative power. British wages took off, zooming past Continental equivalents, as Britain won first-mover advantage in the race to a manufacturing age. Since that time, economic growth, population growth, and complexity itself–the interconnectedness of globalization, collapse of distance, and the triumph of technology–have all expanded on the back of ever-increasing energy consumption. Energy consumption, that is, from fossil.

The IEA was not the only emissions-tracking group offering up hopeful news this spring. Global GDP growth is pressing ever onward, by 3.4 percent in 2014 and 3.1 percent in 2015, according to the IMF, and 21 countries are even reducing carbon emissions while growing GDP, according to a survey drawn up by World Resources Institute.

Familiar names populate the list, like Germany, currently undertaking aggressive decarbonization known as Energiewende, and Sweden, which has been on a decoupling glide path for decades. But this is not exactly news. Northern Europe is a veritable playground of cutting-edge infrastructure and policies that optimize for human well-being. When we dream of the future, we typically dream of Denmark.

Accordingly, the biggest surprise in the new decoupling trend has been none other than the United States. Even though U.S. energy intensity began its clear decline in the mid-1970’s, there was reason to doubt because the U.S. has, since that time, outsourced so much of its manufacturing. Claims of decarbonization ring a bit hollow if you are simply going to re-import goods that are made in someone else’s factory abroad. So, offshoring was not only a phenomenon affecting U.S. labor, it likely restrained U.S. emissions too.

For the last decade, however, declining energy intensity in the United States has started to look more real. In a five-part series last year, The Renewables, TPM covered new directions undertaken by the U.S. as it seeks to catch up to regions like Europe. New policies from the EPA have given a soft push to America’s coal plants, many of which were operating well past their design life, tipping them over the edge into closure. More immediately, concerns that the country’s still young revolution in solar and wind would stall out were allayed when, in the Congressional session at the end of last year, tax credits were extended for both industries.

In super-sunshine domains like California, buildout of utility-scale solar has been so rapid, that combined with rooftop solar, the state already sees days when electricity generation spills over, into surplus. That’s called overgeneration, and many predicted we wouldn’t see the phenomenon until years from now.

Growth Problems Good, Growth Problems Bad

Many wonder if current declines in emissions from both the U.S. and China may be due to sluggish economic expansion, instead of the very real gains each country has pursued in smarter use of energy. In truth, one trend is likely driving the other. Slow growth incentivizes more efficient use of energy—green buildings, expansion of public transit—in an effort to squeeze out gains from lower GDP. A just-released report from Lawrence Livermore National Labs importantly noted Americans are not just using less energy, they are wasting less too, as of 2015.

But it’s still the case that when fossil fuel consumption falls, the role of renewables temporarily looks bigger. “The IEA is saying global emissions peaked almost entirely because of renewables, but really the slowdown is because of coal, and China,” says CICERO’s Glen Peters.

If you conduct a simple accounting of world economic growth and emissions declines, you can understand Peters’ view. OECD emissions have been declining for almost a decade. But China’s (and other developing nations’) kept rising, wiping out the OECD’s achievement. Global energy-related CO2 emissions rose from 28.8 gigatons in 2007 and kept rising steadily to 32 gigatons in 2013, finally coming to rest at 32.1 gigatons for the past two years, according to that just-released IEA data. It wasn’t until China’s economy slowed–forging less steel, exporting goods at a slower rate, building less infrastructure–that the total carbon output of the world finally leveled out.

Typically more concerned with goods output than carbon output, economists have been alarmed at China’s slowdown. They have feared for two years now that China might crash, which would unleash a totally separate set of problems.

The benign view is that China is trying to transition to a more balanced economy, where the Chinese themselves finally consume some of their own production.

“But a shift to a consumer economy could foretell much stronger growth in future oil consumption,” says Peters. “If China does transition to a new normal, this could extend the drop in coal consumption but shift the economy’s dependence onto natural gas, and oil.” Having built up its wealth from decades of coal-fired manufacturing, China may embark on a new phase, filling up driveways with cars, and homes with appliances.

Image from shutterstock.com Copyright: Photobank gallery

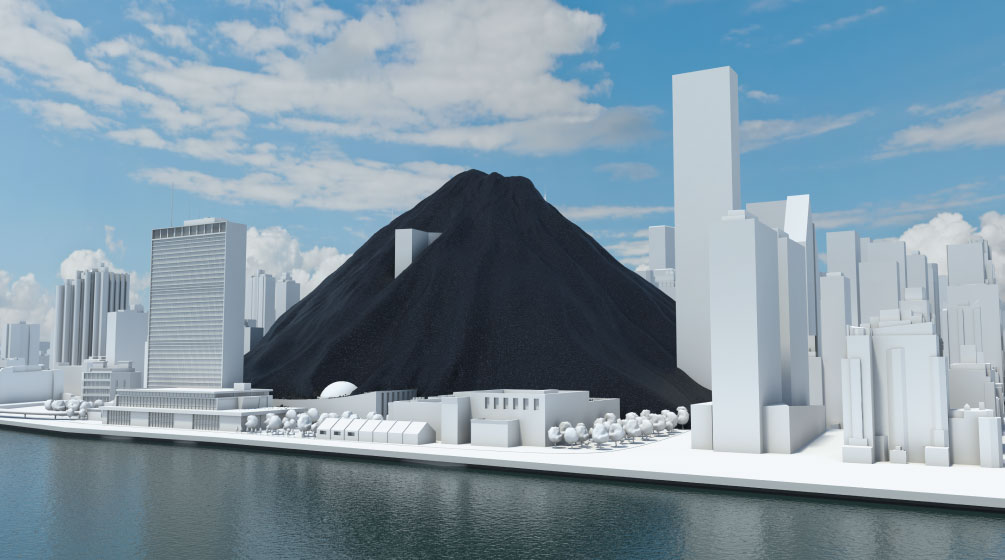

And even if Chinese emissions have leveled out, it’s a high plateau.

“From an emissions standpoint, peaking doesn’t really solve the problem. Emissions have to go into outright decline [globally]. and I think it’s more likely China’s emissions may have an extended plateau, and then maybe a decline much later,” says Peters.

The Road Less Travelled

A remaining, enormous risk for the resumption of future emissions growth comes from a familiar place: cars. Should China follow the historical example of oil use in the United States, after the U.S. itself transitioned to a consumer economy, the outcome would be grim. The U.S. nearly doubled its total energy consumption, from 54 quadrillion BTU in 1965 to 101 quadrillion BTU in 2007, largely through oil.

If China should follow such a path, from super-high levels of manufacturing growth to consumer growth built around cars, then any outright declines in global emissions will occur much later this century, if at all. And given current climate models, we simply don’t have that kind of time.

In search of some optimism, we reached out to energy analyst Ramez Naam, author of The Infinite Resource: the Power of Ideas on a Finite Planet (2013).

“A few years ago, I would have told you that transportation would be very, very slow to decarbonize, that electric vehicles would be fringe, and that we absolutely had to have carbon-neutral drop-in biofuels. My mind has changed on that. Electric vehicles are going gangbusters. They’re still only 0.1 percent of all vehicles on the road, roughly where solar was 15 years ago. But they’re growing faster – 60 percent annual growth this year.”

Naam’s constructive view comes on the heels of Tesla’s spectacular release of the Model 3, which garnered 325,000 pre-orders for an electric vehicle not yet in production. That’s more than twice the 145,000 EVs of all makes and models sold in the U.S. yearly. A more affordable EV like the Model 3 points to another long-held dream: that transportation could un-tether from oil.

That vision is harder to realize, however. Converting society to EVs is not like downloading an app. Rolling out a revolution in electric vehicles is deeply dependent on economic cycles–and most important, drivers turning in their old cars.

However, the positive trends for EVs are showing up, at least in the developed world. When we spoke to Glen Peters in Oslo, he reported Norwegian EVs were already nearing 3 percent of all cars on the road. Here in the U.S., EV adoption rates are, of course, much higher in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Naam says this is exactly what you would expect. Importantly, “there are network effect tipping points,” says Naam. “Once there are enough chargers out there, it becomes easier to own an EV. There are now more EV charging stations on Manhattan than there are gas stations.”

Two paths now lie ahead for future oil use, and much depends on choices made in China, and India. If the world’s two most populous countries make sure a citizen’s first car is likely to be an EV, then future emissions growth from oil will be greatly reined in.

More good news: India just announced it would like to ensure that 100% of vehicles on the road by 2030 are electric. If that goal seems far-fetched, consider that India, starting with only 3 GW of solar two years ago, will have 20 GW of solar installed by next spring, as part of its goal to get to 100 GW of solar by 2022. Big countries, starting from small bases, can accomplish a lot.

How close are we, then, to some crossover point when EVs do indeed become the first choice for every new car owner on the planet? Naam likes to point out that “electric vehicles are just simpler machines than fossil fuel vehicles. They have far fewer moving parts. They suffer less wear and tear. They need less maintenance. And the energy for them is cheaper. So today, the per-mile cost of an EV is already lower than the per-mile cost of gasoline vehicle. And that will drop.”

A key driver for future EV adoption in China could also come through policy. Tightening emissions standards for all cars would be the most effective way to kill off petrol-based cars, further shifting demand to EVs. However, according to Naam, free-market forces will likely take over regardless.

“A decade from now, it may cost half as much per mile to ride in an EV than it does to ride in a gasoline-powered vehicle,” says Naam.

Buildout Rates and the Future

Global emissions have flattened before, only to rise again. For short periods, global emissions have even fallen, only to, yes, rise again. Indeed, in a just-published paper from CICERO’s Glen Peters, he and his co-authors find that although China’s coal use did in fact decline recently, its total emissions probably haven’t. Why should we congratulate ourselves, therefore, or mount any expectation that this time will be different?

Here’s why: because suppression of fossil energy growth has already begun. Costs, in partnership with policy, are driving the changes.

Yes, it takes a lot of capital to build a utility-scale solar plant in the Chinese or California desert. But guess what? It takes a lot of capital to build a new coal or natural gas power plant, too. The difference is that once that solar plant is constructed, the operational costs drop very rapidly. Governments that need to bring lots of new electricity users online—in China, in India, in Africa—have realized that once big wind and solar installations are complete, they simply collect free energy. No coal trains, no natural gas pipelines, no oil storage tanks, no smokestacks.

In 2014, 22 percent of all new energy demand — everywhere globally, from all sources — was met by new wind and new solar power. In the same year, new hydropower met 14 percent of new energy demand, and biomass and geothermal met 6 percent. Most encouraging is that in 2014, global emissions still flattened, even though half of new growth was composed of oil, gas, and coal. 2015 will look even better for renewables, and so will this year, and next.

It’s also crucial to remember how consistently wrong forecasts have been about the future growth of renewables. The U.S. energy agency, EIA, recently had to explain its modeling when a 2016 study by Gilbert and Sovacool examined 630 of the agency’s projections between 2004 and 2014 and found fossil energy growth was consistently overestimated and renewables — especially wind and solar–underestimated. (Gilbert co-authored an explainer of the study in an April posting at The Hill).

The recurring problem in the EIA’s modeling concentrated in one area: costs. Costs for wind and solar power have dropped so rapidly, even private market forecasters have had trouble keeping pace.

As Ramez Naam points out, tipping points in costs are not a future phenomenon. They are here right now. “We have solar beating out fossil fuels, without subsidies, in Chile, in Dubai, in parts of India. And you have 3.6 cent per kwh solar deals being signed in California. Even if you back the subsidies out of that, it’s still cheaper than coal or gas,” says Naam.

While the embedded coal capacity of China and the oil dependency in the United States are admittedly hard problems to solve, it’s now finally rational to ask: what opportunities exist for fossil fuels to grow further, to gain new share, to expand in the two largest economies over the next five years?

China plans to add 15-20 GW of new solar capacity every year between now and 2020, to arrive five years from now with 150 GW of total capacity. The United States is using 5 percent less oil than it was in the year 2000, despite adding another 40 million people to its population.

Combined wind and solar are already 4 percent of total power generation in China, and 5.6 percent of power generation in the U.S. Those look like small numbers at first glance, until you consider how much fossil fuel growth is suppressed each year. Bankruptcy stalks the global coal sector primarily for this reason: Renewables have finally reached the point where they, not coal, can meet the needs of new electricity growth.

Given the growth also of hydropower and new nuclear in China–and paired with U.S. support for wind and solar industries–, it’s no longer clear that fossil fuels will experience much, if any, net growth in Chinese and U.S. electricity systems in the near future.

Both China and the U.S. are already on pace to see wind and solar supply 10 percent of their electricity on or shortly after the year 2020. Meanwhile, the global oil market remains a mess, not only because of ample supply, but because oil consumption growth has been slowing for years.

If you think renewables growth will suddenly come to a halt, it’s increasingly necessary to explain why. Betting against renewables, betting against their rapidly falling costs, and betting against big shifts in consumer behavior and climate consciousness have proven, so far, to be very bad bets indeed. Global utilities have been hammered trying to bet against wind and solar. Same with the coal industry, and now the oil industry.

Amazingly, cheap oil prices haven’t really spurred the huge rebounds in oil growth that used to happen in decades past. Many consumers who buy EVs report they don’t care whether oil prices are high, low, or somewhere in between. Perhaps they, like China and the U.S., are ready to join the climate game.

Lead image source: One Day’s Coal Consumption 2013 from CCS a 2 Degree Solution Film via flickr.