It was the least surprising October surprise in recent memory. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, in an interview with Bloomberg News, was asked about the federal deficit, which ballooned to $779 billion last year after the implementation of the Trump tax cuts.

“It’s very disturbing, and it’s driven by the three big entitlement programs that are very popular: Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid,” McConnell said matter-of-factly. “There’s been a bipartisan reluctance to tackle entitlement changes because of the popularity of the programs. Hopefully at some point here we’ll get serious about this, we haven’t been yet.”

Democrats pounced. House and Senate leadership, candidates running in blue states, purple states and deep red states, all unified to call out the Republican game plan: run up deficits with tax cuts on the wealthy and corporations, then point to those deficits to justify slashing social insurance programs. Never mind that Social Security and Medicare are self-funded and don’t contribute to the deficit. “This is a classic Republican bait-and-switch,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) on a conference call days after the remarks. “A vote for Republican candidates in this election is a vote to cut Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.”

Liberals certainly know how to mobilize when social insurance programs are under attack. But McConnell didn’t need to say anything to make conservative desires clear. From 1936 GOP presidential candidate Alf Landon, who called Social Security a “cruel hoax” on American workers, to future President Ronald Reagan’s recorded warnings in the 1960s that Medicare will lead to socialism and the destruction of American democracy, to George W. Bush’s failed attempt to privatize Social Security, Republicans have longed to deny earned benefits, leaving the elderly and the poor stranded.

Though Donald Trump has insisted that he would never cut Social Security, and recently asserted (without proof) that Democrats would preside over the destruction of Medicare, his administration has, too, had its knives out for social insurance. His budget proposals have suggested trillions of dollars in cuts. His top economics officials have joined McConnell in urging trims. Behind the scenes, his agencies have aggressively sought to weaken and limit social insurance, in partnership with willing states.

If Republicans hold onto Congress — or even if they keep one chamber — threats to social insurance will loom over every fiscal deadline, every behind-the-scenes congressional huddle. Democrats have shifted strongly, not only defending these programs but advocating to expand them. So social insurance is on the ballot this November, in a very real way. But the possibility of the GOP attaining its lifelong dream still flickers, and not even a blue wave can fully snuff it out.

![]()

Like a Bond villain describing the entire plan while 007 is tied up in his lair, Republicans have laid out their blueprint for the future of social insurance programs in great detail. It’s all listed in public documents available to anyone with an Internet connection.

The Trump budget proposal for fiscal year 2019 proposed a 7.1 percent cut to Medicare, addressing “fraud and abuse” and “wasteful spending” while improving the payment system. Over 10 years this amounts to a cut of $236 billion. The administration claims this would merely cut costs with no change in access to care.

The budget also envisions repealing and replacing Obamacare, which would wipe out a Medicaid expansion that has provided 15.5 million low-income Americans with coverage, as well as taxes that extended the life of the Medicare trust fund by twelve years. The Graham-Cassidy proposal that the Trump budget endorses would turn the Medicaid expansion into a block grant program, limiting the number of subscribers rather than enrolling all eligible residents.

Trump’s budget takes a whack at Social Security too. In particular, the budget trims Social Security disability insurance (SSDI) for those unable to work by $71 billion over 10 years. This has been a hobby horse of White House budget director Mick Mulvaney, who in 2017 called SSDI “the fastest-growing program” and “very wasteful,” despite enrollment shrinking since 2014, with an error rate (counting both over- and under-payments) well under 1 percent. Mulvaney famously bragged about tricking Trump into endorsing disability cuts by pretending it wasn’t part of the Social Security program, which it is.

House Republicans went far deeper than Trump in their most recent budget proposal, which included $537 billion in cuts to Medicare and over $1 trillion to Medicaid. Seniors would be encouraged to use for-profit alternative Medicare plans instead of traditional Medicare, continuing the move toward privatization. The budget would also block-grant Medicaid through a “per capita cap,” a limit on reimbursement per enrollee set to a growth rate well below current projections.

Previous GOP budgets authored by outgoing House Speaker Paul Ryan eliminate Medicare entirely, turning it into a coupon program where seniors receive “premium support” for private plans that would grow more and more inadequate over time. Republicans also habitually endorse raising the retirement age. A 2016 bill from Texas congressman Sam Johnson would have elevated it to age 69, while reducing Social Security benefits for those eligible and introducing deeper means testing. Going back to George W. Bush, Republicans have supported transitioning Social Security into private accounts.

You don’t have to be Columbo to figure out the game plan here. Republicans want to scale back social insurance programs. They see dignity in retirement and relief from poverty as a burden on government, and an unnecessary extravagance for undeserving beneficiaries. “It’s really an ongoing, unbroken chain of attack on the New Deal,” said Nancy Altman of Social Security Works, one of social insurance’s biggest defenders.

The net result would further shift risk onto the poor and the elderly, freeing up room for bigger tax cuts for the well-connected. It would also invite private companies — health insurers for Medicare and Medicaid, investment managers for Social Security — to provide social insurance, and take their cut off the top. Though the GOP has thus far been stymied in this kind of frontal assault, it has undoubtedly been the party’s deepest wish.

But frontal assaults are not the only way to mount an attack on social insurance. “Based on the politics and the popularity of the programs,” said Jared Bernstein, former economic advisor to Vice President Joe Biden, “my concern is less that they’ll massively cut them, and more that they’ll implement cuts around the edges that don’t look so bad at first but could eventually do real damage.”

![]()

The 2017 tax cut law included one stealth method that could be used to cut Social Security benefits. Republicans changed the cost-of-living calculation that alters tax brackets annually. Instead of employing a version of the consumer price index (CPI), which measures the year-over-year inflation of a basket of goods that people commonly purchase, Republicans replaced it with “chained CPI,” which adds the concept of substitution.

For example, if the price of beef spikes, a shopper may choose to purchase lower-cost chicken. That individual’s cost of living didn’t increase, technically speaking; they just shifted purchases to fit their budget. Supporters claim chained CPI is more accurate, though they fail to explain how the substitution effect works for big-ticket items like education or health care. A ham might be cheaper than arthritis medication, but it’s not exactly applicable.

If you do the math on the substitutions, you get a chained CPI that’s typically 0.25 to 0.35 percent lower than the other ways the government calculates inflation. That sounds tiny, but it grows every year as the differences widen. Chained CPI adds up to a $128 billion tax increase over a ten-year period, and $500 billion more the next decade. If you added chained CPI to Social Security, you would cut benefit payouts by $230 billion in a decade, also widening over time. It’s a way to raise taxes and cut benefits while claiming merely to improve statistics.

By applying chained CPI to the tax code, Republicans have granted it legitimacy. “We now have it in federal law; they can say why don’t we do it for everything?” said Richard Fiesta of the Alliance of Retired Americans. In doing so, Republicans can point to support from the last Democratic president, Barack Obama, who endorsed applying chained CPI to Social Security throughout the ill-fated debt ceiling negotiations in 2011. (Obama’s budgets finally abandoned the idea in 2014.)

Social Security cutters have also started talking about longevity indexing, which would modify Social Security payouts as average lifespans increase. You can accomplish this through raising the age to qualify for full benefits, or by cutting benefits whenever Americans start living longer. Making cuts automated based on longevity would take personal agency out of it. With Medicare, cost-shifting could serve as a quiet method to make the program stingier, either through increased premiums, means-testing, or higher prescription drug co-pays. Because not everyone might be affected — means testing would only hit high-income seniors, and co-pays could only increase for certain drugs — the subtle shifts could fly under the radar.

![]()

Other damage to social insurance is already in motion: By degrading the basic performance of the programs, the administration makes them less popular. In other words, after claiming for years that government doesn’t work, Republicans are making sure it doesn’t.

For example, the Social Security Administration (SSA), which is responsible for enrolling Social Security recipients and distributing benefits, has seen its budget fall 11 percent since 2010, while 10,000 baby boomers retire every day. The Trump administration proposed another $500 million in cuts in its FY2019 budget. The SSA budget doesn’t even come from general revenue but the $2.9 trillion trust fund, yet Congress can direct how much goes to managing the program, and lately, they’ve put on the squeeze.

This has caused serious disruption. Sixty-four field offices and another 533 mobile offices have closed, while others have had hours cut. Annual benefit statements have been suspended. The average wait time for a hearing on disability applications has jumped 50 percent; tens of thousands have died waiting for adjudication. And the hotline for SSA inquiries is barely functional. “I testified at a Ways and Means Committee hearing, I had a staffer behind me,” said Max Richtman of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. “I said he would call the toll-free number at the start of the hearing. I was on hold the whole time, the hearing lasted an hour and fifteen minutes. Who’s going to stay on the line that long?”

Privatization — pushed by Republicans and many Democrats for decades — has also taken its toll. Most federal benefits like Social Security are now issued through direct deposit, but those without bank accounts use a system called Direct Express, where Comerica Bank provides prepaid debit cards to access funds. This month, it was revealed that fraudsters gained access to cardholder data and drained people’s accounts. Comerica failed to notify victims and took months to rectify disputed claims. In a few cases, Comerica suspended defrauded accounts and the remaining funds in them, and even charged victims fees to reactivate new cards. Medicare Advantage, the private insurance alternative to Medicare, has also been accused of profiteering, through persistent inappropriate denials of claims.

An understaffed SSA or a predatory private partner can sap public confidence in social insurance. “The effort is to make people resent the government,” said Nancy Altman of Social Security Works. If programs are perceived as dysfunctional, they become less popular and more vulnerable to attack.

Altman also notes proposed changes to the selection of administrative law judges (ALJs), which handle all appeals for disability applicants. A Supreme Court ruling in June held that “heads of departments” must appoint ALJs. Altman believes the ruling could serve as an excuse to claim that Social Security’s ALJs were also improperly appointed, delaying thousands of disability applications. Newly appointed, ideologically inclined ALJs could simply deny disability, restricting unable-to-work Americans from needed benefits.

![]()

Administration critics have pointed warily at a recent political appointee as key to undermining another social insurance program. Mary Mayhew, Maine’s former secretary of health and human services, was recently named director of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. She follows a long line of Trump appointees with expressed antipathies to the agencies they head; some have called her the Scott Pruitt of Medicaid. Mayhew, an ex-hospital lobbyist, slashed Medicaid enrollment in Maine by 24 percent, limited welfare and food stamp rolls, and left other funds for the poor unspent. She has been a political activist, imploring other states to forego Medicaid expansion in Obamacare. She now runs Medicaid.

In her new position, Mayhew can push the newest threat to Medicaid rolls — work requirements. The Trump administration has allowed states to require that Medicaid recipients work 20 hours a week or enroll in a workforce training program. While a federal judge has put Medicaid work requirements in Kentucky on hold, Arkansas has implemented them, and Indiana, New Hampshire, and Wisconsin have also received federal approval. Five other applications are pending; Mayhew herself supported work requirements in Maine.

In just two months of implementation, 8,462 beneficiaries in Arkansas lost Medicaid, with another 5,000 at risk come November 1. Conservatives claim that work requirements ferret out freeloaders who are enjoying benefits without any effort, but a paper from Lauren Bauer of the Hamilton Project and two co-authors found few Medicaid recipients refusing to work. “It’s like 1 percent of the group,” Bauer said. Most beneficiaries exposed to work requirements are working, but in high-churn, volatile jobs that don’t conform to the program’s rigid rules.

“Because it interacts with a monthly verification, you have to work at least half the time every month. That’s not how the low-wage sector works,” Bauer explained. Erratic schedules that dip workers under the 20-hour threshold, or seasonal jobs that concentrate hours at one time of year with large gaps in between, would result in losing Medicaid. And economic shocks leading to unemployment would also lead to lost health insurance. “We don’t want to sanction people trying and failing for reasons out of their control,” Bauer said.

Nearly all Medicaid beneficiaries who don’t work are either elderly, disabled, caring for relatives, or suffering from persistent, chronic health issues, which losing Medicaid would only exacerbate. Some states have included health exemptions to work requirements, but they are onerous. “If you’re low-income, sick, and don’t have the Internet, now you have to get a doctor’s note every month to prove you’re sick,” Bauer said. “If you fail that administrative hurdle, you’re locked out of the program.”

House Republicans also added work requirements to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or food stamps) in their version of the farm bill. That’s now in a conference committee with the Senate, but Bauer’s paper estimates that another 4.1 million beneficiaries would be exposed to benefit losses from SNAP work requirements, along with 3.5 million children and 710,000 seniors dependent on food assistance in those households.

In early October, the Trump administration devised another effort to restrict access to social insurance, proposing a change to “public charge” rules that would prohibit certain immigrants from legal permanent residency. The new rule defines a “public charge” as someone who may receive even a modest amount of benefits like SNAP, Medicaid, or Medicare Part D prescription drug subsidies. That applies to far more programs than the old rule; one-third of U.S. citizens would be considered “public charges” under this standard. Immigration officials would then have broad leeway to turn away public charges. “It’s now enough to say, in the future you are going to get SNAP, so I am going to deny you entry into the country,” said Sharon Parrott of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The impact of this is predictable. Immigrant families, which are often mixed between residents and non-residents, would disenroll from benefits out of fear that a family member could be deported. That could affect any of the 4.8 million children with a non-citizen adult in the household who are insured by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Even those who would never face a public charge determination could be confused by the threat. “The administration has taken such a negative view of immigrants, people might shy away from help they might need,” Parrott said.

![]()

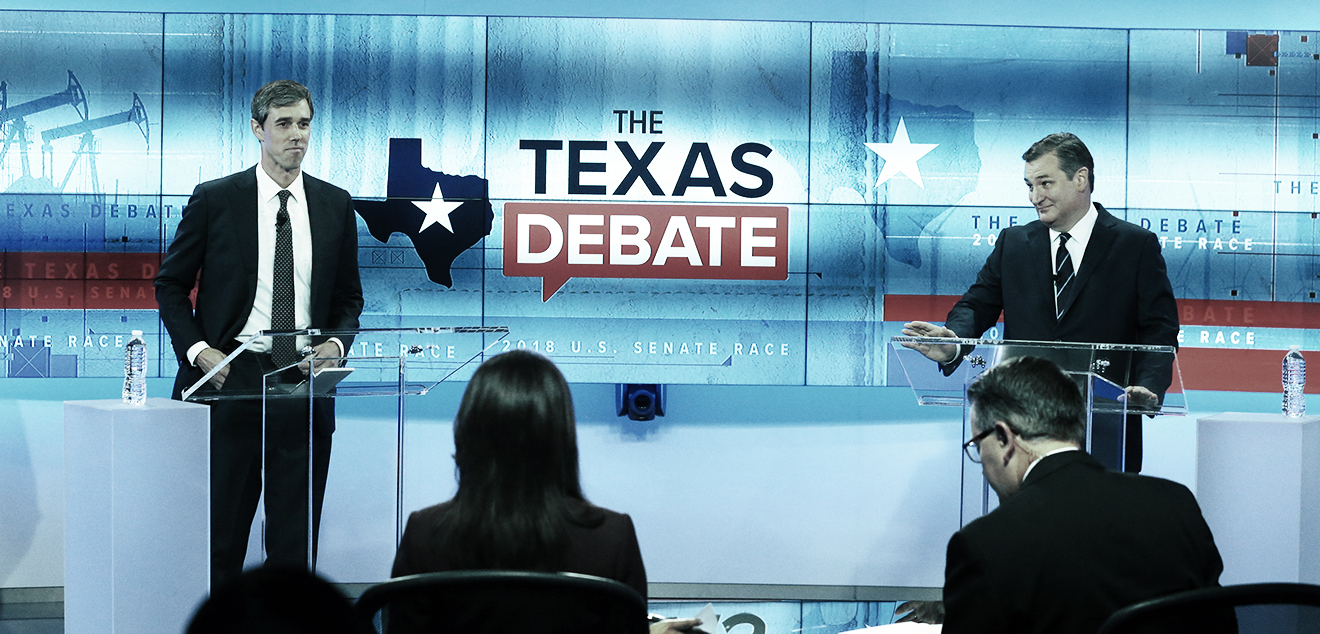

Marco Rubio (R-FL) called for “structural changes to Social Security and Medicare” before the tax cut even passed Congress; Paul Ryan joined him immediately after passage, reminding that Medicare reform “has been my big thing for many, many years.” Steve Stivers, who is running the National Republican Congressional Committee, told CNBC in August that “fixing” Social Security and Medicare was “the right thing to do.” Wisconsin Senate candidate Leah Vukmir put Social Security and Medicare cuts “on the table” last Christmas. Ted Cruz (R-TX) said he would address the deficit with cuts to “socialized medicine,” in other words Medicare, in a recent debate with Beto O’Rourke.

It’s difficult to find a Republican who hasn’t backed up McConnell’s statements about social insurance. “Creating a false crisis and a false solution has been part of the playbook,” said the Alliance of Retired Americans’ Richard Fiesta.

Even the Trump administration, which has claimed to not support cuts, has gotten into the act. In September, White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow told the Economic Club of New York the administration would look at “large entitlements” next year. Kudlow reversed himself a month later, but even then hyped up adding work requirements to several mandatory programs, including Social Security disability, an insane thing to say considering that the entire point of disability is that the recipients cannot work. “I think everybody should take the President and House and Senate Republican leaders at their word,” said Sharon Parrott of CBPP.

A closer look at McConnell’s comments reveals his larger goal: to hook Democrats into social insurance cuts. “At some point we will have to sit down on a bipartisan basis and address the long-term drivers of the debt,” McConnell recently told Reuters, pitching a “grand bargain that makes the very, very popular entitlement programs be in a position to be sustained.” The bipartisanship play fits McConnell’s desire to shield Republicans from blame for starving Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. If he can spread the blame widely, the intense campaign ads Democrats are currently running would be neutralized.

The problem for McConnell is that Democrats have completely changed the way they talk about social insurance. Not long ago, President Obama chased a grand bargain, endorsing cuts to Social Security to reach agreement with Republicans. But by 2016, Obama joined progressive Democrats to promote expanding Social Security. As the other legs of the retirement stool have wobbled — defined-benefit pensions phased out, individual savings non-existent — Social Security expansion has become a mainstream view on the left, with dozens of 2018 candidates running on the idea.

Public polling shows nearly 70 percent support for such a policy, across the political spectrum. A bicameral Expand Social Security caucus launched with 157 Democratic members in September. Similarly, Medicare for All has been endorsed by virtually every leading 2020 presidential candidate and even swing-district Democrats looking to flip House seats. “There is legislation with over 150 cosponsors to expand Social Security, and legislation to add Medicare benefits like hearing, vision and dental,” said Max Richtman of the National Coalition to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. “I think you’re going to see a lot of pent-up advocacy from groups like ours and members of Congress.”

It seems unlikely that this intensity of support for social insurance expansion would lead to collaboration on social insurance cuts. “Even the most centrist Democrat recognizes that these folks just put $2 trillion on the deficit for unnecessary tax cuts, and to give them any kind of a lift in offsetting that is a mistake,” said economist Jared Bernstein.

And yet, even if Democrats sweep into Congress, they will have to contend with Trump agency mischief. In addition, the key to the future of Medicaid will play out not in Washington, but in the states. There are six closely contested gubernatorial races in states that haven’t taken the Medicaid expansion; Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah have Medicaid expansion on the ballot as an initiative. Coverage for millions of poor residents is at stake; a Center for American Progress report estimates that 14,000 lives would be saved annually if all states expand Medicaid. Several gubernatorial candidates could also either push forward or reverse the bid to add work requirements and (in Wisconsin) drug testing to Medicaid. State legislatures will play a role in all Medicaid deliberations, and over a dozen could see party shifts in the balance of power.

If Democrats take only the House, as many forecasts suggest, it would create the divided government McConnell claims should set the conditions for a grand bargain. The legislative calendar could create pressure toward that direction.

Federal appropriations expire in mid-December, during a lame-duck session that will feature dozens of retiring lawmakers and scant public attention. Most observers think a lame-duck spending deal will mainly be concerned with haggling over President Trump’s border wall. But low-key sessions like this are the perfect time to bury social insurance tweaks inside thousand-page must-pass bills. “It’s Paul Ryan’s last hurrah,” said Nancy Altman, pointing to the man most associated with cutting social insurance’s final days in Congress.

Deadlines in 2019 have advocates even more concerned. A February budget deal raised caps on military and domestic spending for two years. But those expire next October. “Without a budget deal, there’s a deep funding cliff,” said CBPP’s Sharon Parrott. Whether it’s Republicans holding one or both chambers of Congress, or just the president and his veto pen, the GOP could use next year’s fiscal cliff as a weapon to enact long-desired social insurance cuts. That February budget deal also lifted the debt limit until March 2019, but in the next Congress that will come back, and along with it potential attempts to hijack the government to serve ideological ends.

The nightmare scenario for social insurance comes if Republicans retain both houses of Congress. They will have dodged a major bullet and perhaps will feel ready to carry out what liberals have called “Phase II” of their fiscal plan. William Arnone of the National Academy of Social Insurance cited the numerous Republican attacks on single payer, even in races where the Democrat hasn’t called for it. “If they can point to the election and say, ‘Our campaigning against Medicare for All worked,’ they will be emboldened to say the people have spoken,” he said. “There will be no enhancements to Medicare, we must save it and to save it we have to cut.”

Thanks to budget reconciliation, Republicans could enact Medicare and Medicaid overhauls with just 50 Senate votes, eliminating the need to bargain with Democrats. (By rule, Social Security cannot be altered in reconciliation.) But even if Democrats gain some foothold in Congress, the ever-present spectre of very serious people pushing “entitlement reform” could seduce them into making a deal. “I’m worried about Mick Mulvaney coming up with really bad ideas that don’t sound as bad as they are, and getting people to fall for a bipartisan view,” said Jared Bernstein. “That’s what I’m going to be watching for and militating against.”

David Dayen is an investigative fellow with In These Times and contributes to The Intercept, The New Republic, and the Los Angeles Times. He is the author of “Chain of Title: How Three Ordinary Americans Uncovered Wall Street’s Great Foreclosure Fraud,” winner of the Studs and Ida Terkel Prize.

Made possible by