It may not feel like it days after President Obama’s re-election, but the 2016 Republican primaries are already well under way. Not only that, these first few weeks may be among the most critical moments in the race.

Nothing shakes up a party like a presidential defeat. After months, even years, of striving to project a unified front behind their nominee, Republican leaders are suddenly free to test out new messages and positions that previously would have been heretical. These early forays into uncharted territory could bolster their standing within the GOP, but could just as easily backfire if the party base rebels.

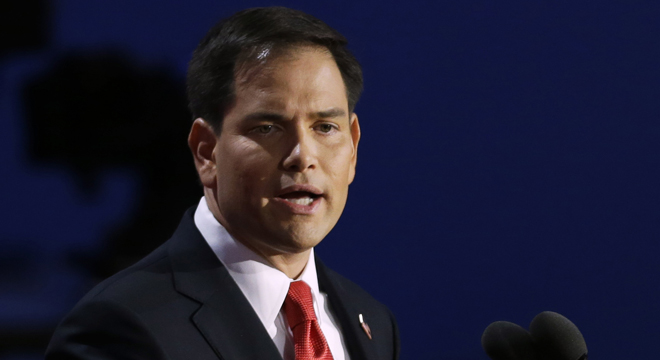

Take Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), who has quickly become the face of a new push by Republican elites to repair their standing with Latino voters. Rubio has called in the past for a revised DREAM Act and issued a statement after Obama’s victory calling on the GOP to appeal to minority communities. But he’s yet to go out on a limb yet with a full policy proposal.

Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal (R-LA) — again without naming specific proposals — is experimenting with more populist GOP rhetoric. He knows better than anybody that sending the wrong message early in an election cycle can have serious consequences for a presidential hopeful. Would he be willing to put his name to some fiscal cliff suggestions that require genuine sacrifices from the rich?

“We’ve got to make sure that we are not the party of big business, big banks, big Wall Street bailouts, big corporate loopholes, big anything,” Jindal told Politico. “We cannot be, we must not be, the party that simply protects the rich so they get to keep their toys.”

Paul Ryan has the most to gain — or lose — in sensitive negotiations with Democrats to avert an austerity crisis. An unpopular deal, especially one that raises taxes, could threaten his current role as champion of the conservative wing. He’s also tied himself closely to Romney’s unsuccessful campaign, another move that could be perilous if the former nominee falls out of favor for failing to unseat Obama.

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R-NJ) has boosted his national profile by working closely with President Obama to respond to Hurricane Sandy, but generated grumbling from Republicans who accused him of undermining Romney days before the election.

And Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) is looking to carry on his father’s legacy with a pro-immigration, anti-drug law platform aimed at winning over young voters and minorities.

If it seems early to take this kind of positioning seriously, consider the moves made by the 2008 field in the immediate aftermath of Obama’s first election.

It’s hard to believe now, but the popular punditry then — as now — was that Republicans needed to moderate their policies and tone to compete with Obama. Several Republicans considered likely presidential candidates made big bets on this new era of bipartisanship and went bust. Florida Gov. Charlie Crist embraced Obama to help promote the stimulus. Now he’s not even a Republican anymore. Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman, another popular executive, decided to take a post with the Obama administration as ambassador to China. He returned to America to find his improved centrist credentials were useless as a presidential candidate in the new GOP.

On the flipside, other would-be candidates pushed their chips in the other direction. Texas Gov. Rick Perry became one of the first major politicians to embrace the burgeoning tea party movement and even suggested in April 2009 that the state might secede “if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people.” That decision helped get him past a tough primary challenge from the left in Texas and propelled him into the GOP presidential campaign as a brief frontrunner.

In perhaps the most important decision of all, Mitt Romney sided with conservatives by opposing emergency loans to auto companies in a New York Times op-ed entitled “Let Detroit Go Bankrupt.” It was published at the identical point in the election cycle we’re in now: November 18, 2008. Romney guessed correctly that the party was more likely to move right before it swung to the center, but also kept some caveats in his op-ed in case things went the other direction. The result: a confusing please-no-one stance that hounded him throughout the election.

By the time the actual Republican primaries were in sight, the candidates’ policy platforms were so similar as to often be barely distinguishable. Many of the candidates quietly phased out proposals to address issues like climate change that had fallen out of favor with the base since the last cycle. But that initial period of 2008-2009, before there was a clear consensus for them to grab hold of, offered real insight into their instincts: Romney as cautious follower, Perry as activist rabble rouser, Huntsman as feelgood centrist. Their successors deserve close attention as they walk the same perilous path themselves.

This post has been updated.