Conventions present the face of the party to voters. The Democrats of 2020 are the party of democracy, character and competence (contra Trump) and social inclusivity, with an emphasis on women and minority groups. Programmatically, they promise a continuation of the Obama years, for instance, incrementally shoring up the Affordable Care Act. (The words “public option” were notably missing from Biden’s speech.)

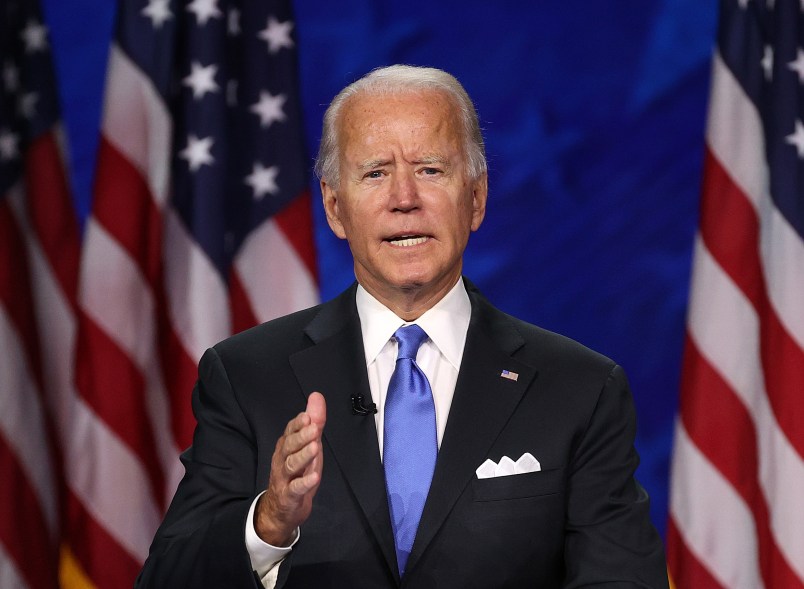

That’s very similar to the party of 2016 except that the appeal to democracy, character and competence is much more telling because of how Trump has actually behaved as president. (Many Americans including me believed he would turn presidential once he won the election.) The most effective appeal to a united front against Trump was from Barack Obama — his speech, with its backdrop of 1787, was historic — but Biden (whom I watched with trepidation) was pretty good.

This united front approach could very well work in 2020. It already did in 2018, even when the economy was still buoyant and China’s deadly bats were still in their caves. But it’s worth noting, perhaps, what was missing from the Democrats’ appeal. These omissions may not be important in 2020, but they will be important if the party wants to challenge the post-Trump Republicans.

The Democrats in the past have alternated between being the party emphasizing economic growth (Kennedy’s “get the country moving again”) or redistribution (Mondale’s “making the rich pay their fair share”). Biden’s party, as viewed at the convention, was a party of redistribution. There were scattered appeals to growth (Bloomberg’s speech). There was mention of the “Green New Deal” and “Infrastructure” but no attempt to visualize or in other ways dramatize the promise of economic growth in these abstractions. “Build back better” is a tongue twister, but lacks content. America remains a world leader in high technology, but you wouldn’t have known it from the convention — except for the magic of the virtual presentations.

While there was much said about the Trump administration’s failure to combat Covid-19, the Democrats made little effort to present themselves as the party of science. Former diplomats were featured; religious leaders and religion were promoted, especially on day four, but I didn’t see scientists and scientific achievements. The one exception was a short spot for a former surgeon general. This may be because I was away from the TV or watching baseball when Francis Collins or Kizzmekia Corbett came on, but if not, this is a peculiar omission and is tied, I think, to the party’s failure to present itself as the party of economic growth.

Finally, the party that succeeds in American elections is usually the one that captures the great middle of the electorate: Jackson’s party of the “common man,” Roosevelt’s “forgotten American,” Clinton’s “forgotten middle class.” Trump and Nixon’s “silent majority.” You can usually measure whether a candidate has succeeded in this respect by how he or she scores on questions about whether the candidate “cares about you.”

The Democrats of 2000, 2004, and 2016 failed to make this case. The Democrats of 2020 have a candidate in Biden who embodies this appeal, but much of their rhetoric and the program itself, more clearly reflected the identity politics of 2016 that emphasizes difference and ignores, whether intentionally or not, predominately white, flyover America. The point is not to appeal, as Trump undoubtedly will, only to this America, but to present an image of a unitary American small-d democrat. It may be hard to do,, but the party’s ability to sustain majorities depends on it.