A few more miscellaneous thoughts on Martin Luther King Jr. on this day of remembrance.

One: King was a troublemaker. In many ways, he became more of a troublemaker as he progressed through his life. In key ways, in the final years and especially the final year of his life, he was being abandoned by key supporters and sidelined because he was focusing not solely on race (on which the country was then beginning to build at least a notional elite consensus) but on poverty and democratic socialism and the Vietnam War, issues that divided many of his supporters. It is always important to remember that King died in Memphis because he was there to support a strike not an integration march, though racial discrimination and labor rights were and are impossible to separate.

Today King is seen as almost synonymous with the March on Washington, as though it were his personal effort. That’s not true. He was, arguably, not even the central figure, at least not going into it. But on this front it is always important to remember that the march was called as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Civil rights and equality were at the heart of it. But ‘jobs’ got top billing.

We do not have to agree with every tenet of King’s radicalism. But if the day set aside in his honor is to have any real significance, if we are really to honor him, it is incumbent on all of us to resist the sanitized consensus King we see so much of in American public life in favor of the actual, much more radical person. This sanitization isn’t surprising and in some ways it is even valuable, in as much as it has made King a civic totem about racial equality that almost everyone in American public life must pay respect to, even if they don’t honor it or even believe it. Hypocrisy, they say, is the honor vice pays to virtue. And that’s good. If you see the totality of King’s thought and actions, particularly in the last years of his life, they will likely make you feel uncomfortable. And that’s good.

Two: This from King’s daughter, Bernice.

As you honor my father today, please remember and honor my mother, as well. She was the architect of the King Legacy and founder of @TheKingCenter, which she founded two months after Daddy died. Without #CorettaScottKing, there would be no #MLKDay. #MLK50Forward #MLK pic.twitter.com/qhwSnX9Qmh

— Be A King (@BerniceKing) January 15, 2018

King is singular. It is also important to remember that King’s public career was little more than a dozen years. Coretta Scott King’s lasted much, much longer and she played a critical role preserving and expanding his legacy after his death.

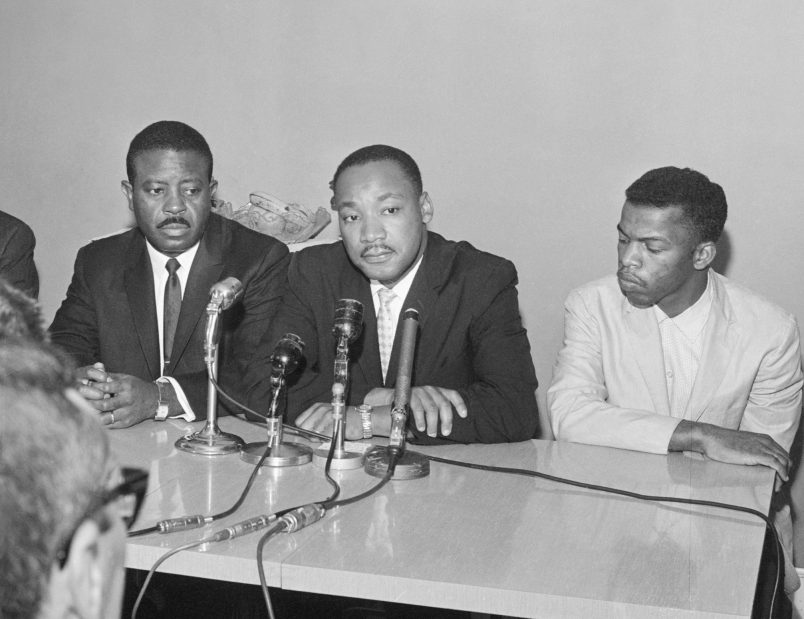

Three: During the Civil Rights Era people often referred to the “Big Six”, six men who headed various civil rights organizations during the height of the agitation for equality and planned the March on Washington: King (SCLC), James Farmer (CORE), A. Philip Randolph (Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Whitney Young (National Urban League) and John Lewis (SNCC). Because of his extreme youth at the time – just 21 when he first came to public notice in the 1961 Freedom Rides – and blessed longevity today, Lewis has long been (since Farmer’s death in 1999) the last living representative of this group. All of us today are lucky to be living in a time when this great elder still walks and acts among us.

Dr. King was my friend, my brother, my leader. He was the moral compass of our nation and he taught us to recognize the dignity and worth of every human being. #goodtrouble pic.twitter.com/2OdUL5clIa

— John Lewis (@repjohnlewis) January 15, 2018

Four: One of King’s most important advisors and collaborators was an out gay man, Bayard Rustin.