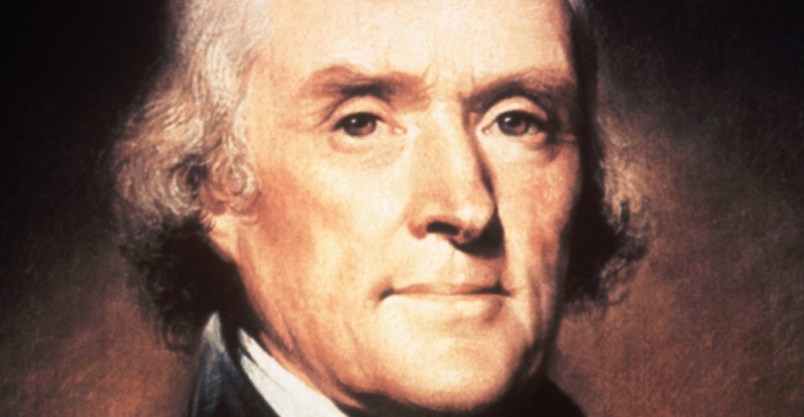

Thomas Jefferson played no direct role in authoring the federal Constitution. He wasn’t even in the country at the time. He was living in France as the U.S. Ambassador. Indeed he was at least equivocal about key elements of the document, despite the fact that much of it was the work of his friend and protégé James Madison, who kept him informed about the progress of events by post from the United States. But Jefferson was of course a central figure in the creation of the American Republic and a critical figure in defining executive power under the federal Constitution both as Secretary of State and one of two principal advisors to George Washington and then, later, during his two terms as President. He spoke clearly to the question at the heart of the Court’s immunity decision and very clearly disagreed with the reasoning and any idea that Presidents weren’t subject to the law.

I should start by saying that we don’t have just Jefferson to go on. You can’t read any part of the discussions of the Constitutional Convention, the discussions leading up to it or the debates over it, without seeing that the idea that the President would be immune from the criminal law over his conduct in office would have struck these people as simply absurd. But Jefferson himself came at the question later from a different perspective, not as a theoretical matter but as a retired chief executive who had actually wielded presidential and prerogative power and believed that at least in some cases he had exceeded his powers in the interests of the nation.

A brief side note: I believe I first came across this in graduate school in another letter of Jefferson’s in which he discussed this matter more closely in the context of he Louisiana Purchase. But I don’t remember the particular date or correspondent. But he makes the same essential points in a letter from 1810 (Letter to John Colvin, September 20th, 1810), two years after leaving office. It’s possible that my memory is erroneous and my recollection is actually of this letter to John Colvin. So if anyone who’s spent time in the Jefferson Papers remember this other letter which I had remembered being written in 1813 or a few years later, please let me know. But for the purposes of this post I’ll focus on the Colvin one so you don’t have to trust my possibly erroneous member of the other.

In any case, here Jefferson addresses the common question of whether a head of state might sometimes be justified in violating the law in the interest of some greater good, saving the country, protecting the country, to preserve the law itself. We can state this question in various ways but we understand the basic concept: is a President ever justified in breaking the law in the interests of the country itself. Often, the question is framed as a case where the authors of the laws in question would have recognized the justice of a future President’s actions if they could know the precise situation in which he found himself.

So what did Jefferson say? His answer has stuck in my head ever since I read it and it has always struck me as the correct answer for republican governance. His answer was yes, it is sometimes justified. But the second part of the answer is the critical. He says that men who take on these high offices are obligated to make these decisions and assume the personal risks of doing so. This can’t be stressed enough. He doesn’t say Presidents or other high officials working at their behest are above the law or immune from prosecution under the law. He says clearly and explicitly that one of the responsibilities of power is that they may face situations in which they must break the law or violate the Constitution in the interests of some higher and more pressing goal and then face the personal consequences of having done so.

To quote specifically:

“The officer who is called to act on this superior ground, does indeed risk himself on the justice of the controlling powers of the Constitution, and his station makes it his duty to incur the risk.”

“It is incumbent on those only who accept of great charges, to risk themselves on great occasions, when the safety of the nation, or some of its very high interests are at stake.”

“[T]he good officer is bound to draw it at his own peril, and throw himself on the justice of his country and the rectitude of his motives.”

We have really the key quote here: “Throw himself on the justice of his country.” This point is crystal clear. Such a leader has to accept the consequences under the law and in essence throw himself on its mercy, arguing that despite the fact that he violated the law it was the right thing to do under the circumstances. Jefferson also makes the point that the public should judge this leader not on the basis of retrospect but on the basis of the facts and exigencies that were known at the time. But none of these points take away from the essential point: a chief executive must come clean about what he did and accept the legal consequences for the decision. He is emphatically neither above the law nor immune from its consequences.

While the modalities would fit those of the early 21st century, the scenario Jefferson envisions is one in which a President takes actions he or she feels they must take and then once there’s time to do so they must go before the public and say, I did this. I think it was the right thing to do. But I’m ready to face the consequences, if you think there should be any, for doing so.

What has always been so interesting to me about this argument is that Jefferson not only says a chief executive must face these consequences but that he may be obligated to take actions for which they will later face such consequences. In other words, it would not be acceptable for a chief executive to say, ‘Well, I think it’s best for the country if I do X. But I could go to jail for doing X. So I’m not going to go there.’ Jefferson says that when you agreed to take on this high office you agreed to take on these personal risks in the country’s interests. So that fear of personal risk isn’t acceptable. Your obligation is to the country, not yourself.

Two secondary points to finish up. I should emphasize that Jefferson makes clear this only applies in extreme, extreme cases. It’s not a matter of choose your own adventure. These apply to extreme cases where time doesn’t afford the possibility of delay, writing a new law, getting Congress to approve something etc. etc. In our modern world of analogies we’d describe these as ticking time bomb scenarios. The other interesting thing is that in this letter Jefferson speaks interchangeably about Presidents and other high officers of government. This can seem confusing. But it makes a separate but related point. These were all high government officials given great power to achieve certain goals and ends. None of them were above the law. In other words, Presidents were not some unique constitutional creature, simply the highest officeholder in the country, serving under the law like everyone else.

To anticipate some rejoinders, it’s quite true: Jefferson didn’t write the Constitution or vote on it. In some highly notional sense his opinion is worth no more than John Roberts’ or Sam Alito’s. But obviously if we’re interested in what the Constitution meant to those at the time, those who were in close contact with those who created it and indeed the people most closely involved in defining presidential power Jefferson is a powerful, powerful fact witness. And we must recognize that in his time, this idea was actually a controversially robust assertion of executive power. I can’t stress this enough. The consensus opinion was simply that of course Presidents have to follow the law. I mean, that’s a good consensus to have! Jefferson was saying that there are some cases in which they may be entitled to and even obligated to violate the law. But then they have to face the consequences. So while Jefferson was in his theoretical meanderings a small government guy, this was actually much more than most contemporaries would allow for what a President might be allowed to do. It seems inevitable that this was in large part because Jefferson had been President, and knew the practicalities involved.

If history mattered to this Court this evidence would bulk very large in any argument. Indeed, I think it’s pretty determinative. But it doesn’t because this decision is something the Court simply created out of whole cloth, indeed a bespoke suit for none other than Donald Trump.