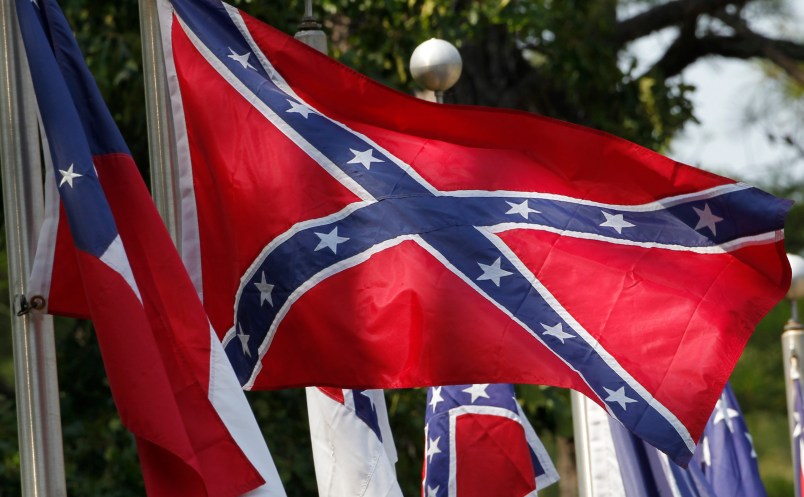

I’ve been telling fellow TPMers in our editorial chats over the last few days that I was genuinely surprised that the Charleston church massacre has apparently proved the watershed that is leading to a wholesale abandonment of at least the Confederate flag (and perhaps other symbols of the Confederacy) from public spaces in the South. Certainly, this is not to discount the shocking scale of Dylann Roof’s crime. But the Confederate flag – actually the Confederate battle flag or flag of the Army of Northern Virginia, you probably would not recognize the actual national flags of the Confederacy – is a damn persistent thing.

(For the actual national flags of the pretended Confederate States of America, see the list of flags at the bottom of this post.)

About 10 or 15 years ago, there was a major agitation to remove Confederate flags from the state flags of various former rebellious states and from the state capitols of those states. Indeed, the then-Governor of South Carolina, a very conservative Republican named David Beasley (1995-1999), came out against the flag for no clear political reason other than that he believed it was the right thing to do. And in part because of that he lost his big for reelection in 1998.

The politics of the Confederate flag in the South actually remind me or did remind me of the politics of gun control, in this very narrow sense. After that big push 10 or 15 years ago, it’s not that people who opposed flying the flag at the South Carolina capitol building or in other states cared about it or opposed it any less. It was just one of things that just seemed like it would never change. Not that many people, not that many prominent people, could or did make good arguments for holding on to it. But in these Southern states it kicked up a silent wall of opposition that was just unmovable.

Just after the massacre Lindsey Graham was saying basically, hey, that’s how we do things down here. Back off. Yet yesterday he was up there on the stage with Gov. Haley (and I really give her credit) saying, it’s time to end this. Also yesterday, the ultra-conservative Speaker of House in Mississippi announced that he supports similar action in Mississippi.

Nathan Bedford Forrest

In Tennessee, Democratic lawmakers and the state’s GOP chair, are calling for the removal of the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the state capitol. Forrest was one of the South’s most brilliant generals, albeit having no formal military training. He was also the founder of the Ku Klux Klan. The original Klan, not the revival of the Klan in the 1920s from which the modern variants descend, was quite different from the organization most of us are familiar with today. But it was worse. It was a paramilitary organization fighting against black enfranchisement and equality during Reconstruction and often by killing and terrorizing black freedpeople and to a more limited extent their white supporters. Nor did he just ‘go bad’ after the war. He oversaw or ordered (some dispute over which) the massacre of black Union troops and white Southern Unionist troops at Fort Pillow in early 1864.

South Carolina Congressman, Senator, Secretary of War and Vice President John C. Calhoun

And in perhaps a reductio ad absurdum (though I would argue it is not in fact absurd) example of the trend, there is now a push in Minnesota to rename Lake Calhoun. Lake Calhoun is named after John C. Calhoun who, despite dying in 1850, eleven years before the Civil War, was in many ways its intellectual architect. (He was also a longtime senator and one-time Vice President.) The growth and sectionalization of slavery was the cause of the Civil War and would have caused it whether or not Calhoun had ever lived. But starting in the late 1820s and through his death, Calhoun articulated a series of constitutional ideas designed to protect sectional minorities (i.e., the South and the planter class) and to lay the justification for blocking federal law (‘interposition’ or ‘nullification’) or leaving the Union entirely (‘secession’). Ironically, and going a decent way toward explaining how on earth a lake in Minneapolis got named after Calhoun, the naming seems to stem from his early career when Calhoun, later the arch southern sectionalist, was a strong nationalist. The naming seems to date from his tenure as Secretary of War in the Monroe administration in 1817.

Before going on, it is important to note that the incorporation of the Confederate battle flag into Southern state flags and flying it at capitol buildings isn’t some relic of the post-Civil War days. It’s quite new. In most cases it goes back a little over 50 years to the 1950s and early 1960s. In other words, the prominent public display of the flag (if not the popularity of the flag itself, though partly that too) doesn’t commemorate the Civil War or the Confederacy, it was the emblem of the ‘massive resistance‘ movement of the 1950s and 1960s in which white Southern state government sought to defy the federal government’s effort to force desegration, black enfranchisement and formal legal and political equality for African-Americans on the South.

So why did this massacre, horrific as it is, lead – apparently – to the complete collapse of support for flying the Confederate battle flag? It’s certainly not that Southern state governments are less conservative or Republican than they were 10 or 15 years ago. Far from it. And more specifically and relevantly, nor are they more progressive on race issues than a decade a more ago. So why? At a basic level, I’m not totally sure, thus my surprise. At some level, of course, it is the sheer horror of Dylann Roof’s crime, his totally unambiguous motivation and his open use of the flag’s symbolism. There’s also a herd affect. Once Nicki Haley decided it was time to bring down the flag it probably became much, much harder for comparable leaders in other states to hold out. But neither explanation, to my mind, really captures the sea change. The best explanation I can think of is one David Kurtz suggested, which is generational. A lot of people who were alive and politically active are no longer with us. And it certainly stands to reason that that generational cohort would have been the staunchest in its resistance to the change.

Flags of the CSA …

First national flag of the pretended Confederate States of America (1861-1863)

Second flag of the pretended Confederate States of America (1863-1865).

This isn’t a mis-sized Confederate battle flag. The second CSA flag incorporated the battle flag on a field of white. The designer, William T. Thompson dubbed it “The White Man’s Flag.” “As a people we are fighting to maintain the Heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race; a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause,” Thompson wrote in 1863.

We might dub this the “Yes the Civil War was totally F’ing about slavery and white supremacy” Flag.

Third flag of the pretended Confederate States of America. (March 1865 to surrender

It is probably fair to say that all the CSA national flags sucked or were wildly offensive, thus the popularity and emblematic nature of the flag of the Army of Northern Virginia, aka, the Confederate battle flag, even during the war itself.