When the news broke Wednesday night of the horrific massacre at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, from the start people asked why this crime, which would have been labeled “terrorism” if the killer had been a Muslim, is merely a “hate crime” or the work of a deranged madman since the murderer is white. It’s a very good question and people are right to ask it. I think the word “terrorism”, as we’ve come to use it, is so clumsy that it might be better to retire the word altogether. But as long as we do use it, it definitely makes sense to apply the label to this crime. But there’s another meaning of the term, or another history, that I think helps us understand much more of the past and the present of what happened Wednesday night in Charleston.

You’ve probably heard of The Citadel, one of the most storied military academies in the United States, which is located in Charleston. As Benjamin Parks explains in this piece from yesterday, the origins of The Citadel are directly linked to the reaction to the Denmark Vesey slave conspiracy that rocked the city in 1822. As you’ve probably also seen in the news coverage over the last two days, Vesey was one of the founders of the Emanuel AME Church. Nor is this connection between The Citadel and the attempted Vesey uprising some coincidence or oddity. It is a particular connection that illustrates a greater and sobering truth: the Southern military tradition, whatever it has evolved into in more recent history, has its roots in the institution of and particularly the preservation of slavery. Whether it is slave patrols, militias focused on putting down slave revolts or musters intended to overawe subject populations – while no institution has a single origin, this basic fact about the history of the American South is unquestionably true. It is particularly so about South Carolina.

Here is one salient fact about South Carolina. It is the only American colony or state ever to have a black majority population. (See correction below, Mississippi eventually became black majority as well.) Except for a brief period just after the American Revolution, from the early 18th century until the first decades of the 20th century, a clear majority of the population of South Carolina was black. Indeed, the seminal history of early colonial South Carolina is entitled Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion.

When we see a monster like Dylann Roof we rightly see the evil and brutality of racist violence. But to understand it, to understand its origins, it is critical to see that it evolved out of a deep rationality and logic. If you hold hundreds of thousands of people in a rapacious and brutal bondage, you are in perpetual danger.The intrinsic violence perpetrated on the slave can turn around on the slaveholder in an instant. The more brutal the slavery, the greater the danger. And this is all the more so if the slaves outnumber the free population. You cannot understand the history of South Carolina or the American South or for that matter the entire United States without appreciating this simple fact.

If southern whites in the days of slavery were quick to horrific acts of violence against black slaves or the small free black population, this wasn’t born of a character flaw. It was rooted in a palpable knowledge of the intrinsic violence and danger of slavery. They were scared and they were right to be scared.

To sustain that kind of regime requires not just violence but exemplary violence – violence used for the specific purpose of inspiring terror and ensuring compliance.

If this all sounds too much like a college theory seminar, don’t kid yourself. Read the letters and laws of planters and settlers in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and the need to overawe and episodically terrorize subject populations is never far from the surface. It is frequently and explicitly discussed. Nor is it restricted to the American South. The difference is simply that it persisted in the South and intensified because of the way that chattel slavery evolved throughout North America.

My familiarity with this comes not just from the South but even more from the part of the country we rightly identify as the cradle of anti-slavery, New England. Despite all the talk about Max Weber and the protestant work ethic and all the rest, the New Englanders wanted slaves too. It was simply for a mix of climate and other historical contingencies that their history didn’t turn out that way. At the very outset of settlement, the progenitor of one of Massachusetts most storied families, Richard Saltonstall (a Saltonstall was in the US Senate as recently as 1967), was brainstorming about ways to find a source of cheap labor to create an engine of true wealth. The obvious path forward was to acquire slaves. And a decade and a half later leaders of the Massachusetts enterprise could be found brainstorming a plan to start a war with the Narragansett Indians of what is now Rhode Island in order to enslave them en masse and swap them for ‘seasoned’ African slaves from Barbados.

New Englanders never got the mass enslavement many wanted. But the form of brutal violence we know more in the South they practiced on the native population who they lived intermingled with for several decades during the 17th century.

Contemporary rendering of the Pequot Fort massacre

Only a few years earlier, the New Englanders had wiped out a potent nearby tribe, the Pequots, in what is now southeastern Connecticut. The main engagement of the conflict came when a settler army surrounded the main Pequot Village and massacred or burned alive some 500 men, women and children while the main Pequot fighting force was in the field. Hundreds more were killed in the ensuing weeks and the morale of the Pequot fighting force collapsed in the face of the deaths of so many of their families. This not only cleared land for new settlement. The first accounts also explicitly noted the salutory effect the massacre would and did have in overawing the region’s native population and making them compliant.

“For having once terrified them, by severe execution of just revenge,” one settler wrote for an English audience, the settlers “shall never hear of more harm from them, except, perhaps, the killing of a man or two at his work, upon advantage, which their sentinels and corps-du-guards may easily prevent … They shall have those brutes their servants, their slaves, either willingly or of necessity, and docible enough, if not obsequious.”

The reference to sentinels and corps-du-guards is notable for it captures the militarized nature of the early settlements and the importance, frequently noted by settlers, of regular military musters and displays of unity to inspire fear and terror.

In New England the conflict was largely with native tribes since African slaves never amounted to a significant percentage of the population outside of a few pockets of Southern New England. But the patterns were similar. Servitude or forced compliance of any sort is not just intrinsically violent. It often requires exemplary violence to instill the terror that obedience and compliance are based on. This is particularly so in societies where state structures are weak. And societies based on this sort of pervasive violence are ones in which a vital rule of law has great difficulty taking root.

As Gregory Downs noted yesterday in his article on Juneteenth and the end of slavery in Texas, as Southern planters drove slaves into Texas ahead of the Union armies or tried to keep them enslaved even as the slaves knew slavery had been abolished by the federal government, planters resorted to killing hundreds of African-American former (and, they hoped, future) slaves to terrify others into compliance, even as slavery was in its death rattle.

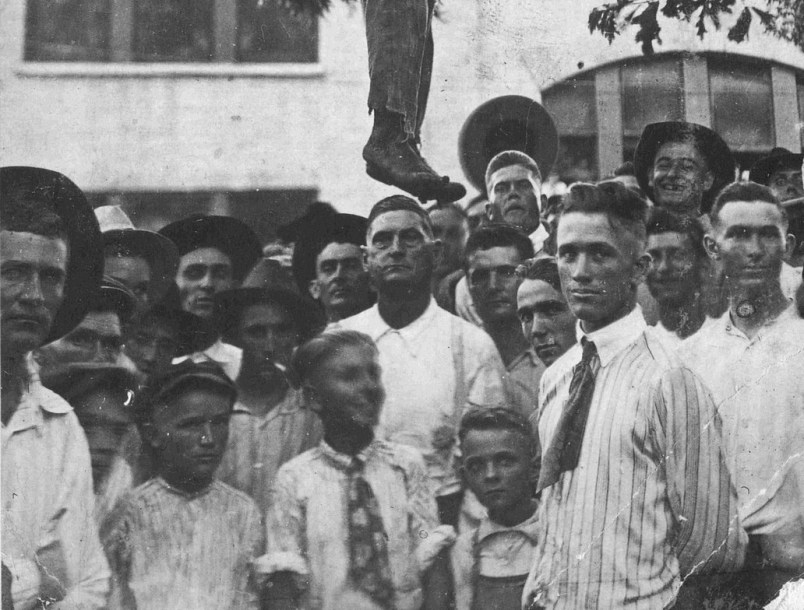

We can see this in New England in the 1630s, more than two centuries later as planters desperately tried to preserve slavery on the run from the US Army. Terror of this sort of is by design and necessity brutal and public. Consider how lynchings are inherently and uproariously public, the carnival atmosphere of the killings, the bodies left to hang and be seen. And it is this thread that carries through with the history of mass terror campaigns white paramilitaries carried out during Reconstruction and the history of lynching and mob violence against African-Americans in the South through the late 19th century and well into the 20th century.

This isn’t to suggest nothing has changed. The racial world we live in today is utterly transformed from what it was a century ago. Then white mobs in the South (and not only in the South) killed African-Americans with impunity and frequently with the passive or sometimes overt support of elected officeholders and the law enforcement of the day. Today a barbarity like the Charlestown church massacre – whatever racial injustices we have today and we have many – are roundly condemned almost universally, if sometimes awkwardly or feebly. Not to recognize this watershed difference is to dishonor the millions of Americans who have worked, suffered and in some cases died to effect the change. But Dylann Roof and his massacre are still the lineal descendent of these earlier horrors.

You can call these artifacts and barbarities of our past evil. And they are evil. But calling them merely evil diminishes their gravity and awfulness because it obscures the fact that such barbarity is necessary to preserve certain social systems and racial orders. Racial violence in America has always been intrinsically connected to terror. And not “terror” in the modern sense of mass casualty attacks meant to drive press attention and fear by people who are not in power. But in a far more direct sense: violence to inspire terror to solidify control and dominance.

Correction: A small but significant correction. I was wrong. South Carolina was not the only state with a black majority. I think I was projecting my knowledge about South Carolina’s colonial period – its unique status – on to the Ante-Bellum period. But TPM Reader AC wrote in to tell me that Mississippi also had a black majority in the early 19th century. And sure enough he’s right. I wasn’t able to check each census. But at least in the 1850 and 1860 censuses, Mississippi also was a black majority state. Louisiana had a bare majority as well. Not terribly surprising, considering that Mississippi was the top cotton producing state on the eve of the Civil War and was ground zero for racial violence throughout the 20th century.