I wanted to flag to your attention this opinion piece for Robert Kagan in The Washington Post. It is an overarching look at the US mission in Afghanistan. Fundamentally it is an apologia, a defense. But Kagan is significantly more sophisticated and thoughtful than most of the more editorially kinetic defenders of the mission. So even while I think he’s mostly wrong and often disingenuous about recounting these events in which he played an important role you can nonetheless learn a lot about the last twenty years from reading his account. Be cautious, though, because the real essence is the many things left out.

One thing that Kagan is right about is this: Many retrospectives say the US went into Afghanistan with hubris and optimism and a mission to build a Western style democracy in Afghanistan. That’s not true. The US invaded Afghanistan because we were scared and angry. Kagan focuses on the “scared.” “Angry” was just as much it. But it was in the nature of that moment that the two were so fused that it was difficult to distinguish them.

Did some oppose the invasion? Sure. But not many. This is validated by congressional votes at the time, public opinion polls and I think just the lived experience of those who were adults at the time.

This is hardly surprising. Let’s recall the circumstances. The US was the victim of a catastrophic terrorist attack, as ingenious in its formulation as it was evil in its substance, to paraphrase a contemporaneous summation by Rick Hertzberg. The US knew very quickly who was behind it, al Qaeda, a group operating openly in Afghanistan as the guests of the quasi-government, the Taliban. The US gave an ultimatum to the Taliban to expel or turn over al Qaeda and the Taliban refused. The most generous read would be that the Taliban equivocated a refusal.

The ultimatum that the Bush administration used as its premise later to invade Iraq was clearly bogus – it was fairly clear that it was bogus in advance and was proven such when the Iraqi government finally acceded to the demand and the US invaded anyway. I suspect we would have been satisfied with a handover or expulsion of al Qaeda, though it’s quite possible that the relationship between the two groups made that all but impossible and the US may have required a surrender simply too abject for the 2001-era Taliban to contemplate.

The rest is history.

It’s also worth remembering that the US didn’t really invade and topple the Taliban. More accurately, we weighed in from the air and with special forces teams and shifted the balance on the ground between the Taliban and their existing enemies – existing military formations – within Afghanistan.

Kagan suggests that the US attitude after the fall of the Taliban government was less “bring it on” than “what do we do now?” As so many other parts of his essay, there’s a real sleight of hand here. But to a significant degree he’s right. The Republican foreign policy establishment was very down on “nation building” in the 1990s. That was mostly true of its neoconservative wing. But that wing wasn’t as clearly in control as people later came to think. It was a mix of that group and what we might call militarist unilateralists, people like Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney. It was hawkish and internationalist Democrats who were saying you can’t just blow everything up and then leave or you’ll have to go back again. This was before “draining the swamp” was coopted as a Trumpist tagline. Twenty years ago it was about stabilizing the failed state breeding grounds or safe havens of international terrorist groups. Rumsfeld had a different take: We’ll drain the swamp. And if swamp fills up again we’ll drain it again.

It’s worth remembering that global counter-terrorism or even the Greater Middle East was not even remotely the Bush administration’s agenda before 9/11. They were vastly more focused on Great Power rivalry with China and beating up on rather than talking to two or three minor powers then known as “rogue states.” The Bush 2000 campaign actually had what one might call a minor side hustle trying to build an electoral constituency of Muslim Americans by opposing the 90s version of aggressive counter-terrorism surveillance of Muslim communities in the United States. Of course everything changed on 9/12 and much of the history of the subsequent year is the story of how the US went from the cataclysm of 9/11 after which supposedly “everything changed” to doing a slightly souped up version of what the team had wanted to do before 9/11 – which was to kick the ass of one of the aforementioned “rogue states” – i.e., Iraq.

But at the start there was more than a bit of “what do we do now?” One of the most destructive and consequential stories in recent American history is the alchemy by which fear and rage transmuted into a heady though brittle form of optimism over the following year. The shift had deep roots in American history; it had far more immediate roots in Republican foreign policy thinking during the Clinton years, when America had a window of easy omnipotence on the global stage. But it still represented a significant, even tectonic shift. It was a neo-Imperial, often explicitly imperial turn in US foreign policy thinking and even more US foreign policy action. I tried to chart some of this turn in a January 2004 book review essay in The New Yorker: “Power Rangers: Did the Bush Administration create a new American empire-or weaken the old one?”

Here’s brief passage …

For leftist critics of America’s role in the world, it has long been a baleful article of faith that the United States is an agent of “neo-imperialism,” exerting its power through global capital and through organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. After September 11th, a left-wing accusation became a right-wing aspiration: conservatives increasingly began to espouse a world view that was unapologetically imperialist. You could watch this happening in Washington’s think tanks. Over their lunchroom tables, in their seminar rooms, on the covers of their small magazines, the idea of empire got a thorough airing—particularly among ideologues close to the policymakers planning the war on terror. At a panel discussion in the middle of 2002, I first heard “Middle East reform”—as in making the Middle East democratic and bourgeois—spoken of the way people speak of welfare reform. As the military historian Max Boot wrote in The Weekly Standard, “Afghanistan and other troubled lands today cry out for the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets.”

Everyone could admit that there were disreputable aspects of the old empire. Yet what would be wrong with a truly enlightened version of foreign rule? “There’s general agreement that there was a mistake that the Brits made, which is that they allowed the imperial administrators to perpetuate a kind of snobbishness over the Western-oriented gentlemen,” one of these conservative thinkers told me last spring, just before the start of the war. “We think these are the lessons we have learned. And that, therefore, imperialism as practiced this time will be different.”

For years Democrats of a certain stripe grabbed hold of the phrase “reality based community” as their half tongue-in-cheek moniker. The quote originates in a 2002 interview the author Ron Susskind did with a person he identified as a “senior advisor to [President] Bush.”

Here’s how he described it in The New York Times in late 2004 …

The aide said that guys like me were “in what we call the reality-based community,” which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

It’s easy enough to make fun of this quote. And we should make fun of it. But we should understand it first. The idea is that there are some people who examine the facts of the situation and then operate on the basis of that knowledge to achieve their aims. Then there are other people who use power to change the facts in ways that benefit them. This understanding of possibility and power is at the center of that shift that brought the people then running American foreign policy and to a significant degree the rest of the country from the fear and rage of September 2001 to the wild exuberance and sense of possibility over the course of 2002.

Of course this wasn’t the end of the story. After less than six months the US had dropped its focus on Afghanistan and moved on to Iraq, even redirecting military assets out of Afghanistan while the US military was still trying to track down fugitive leaders of al Qaeda. But of course the mission didn’t end, only the focus. Democrats big argument at the time and for years after was that it was a mistake to invade or focus on Iraq, which had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks, while leaving our job in Afghanistan unfinished. As Democrats looked fitfully for affirmative arguments against invading Iraq amidst a pro-war political environment still suffused with fear and militarist exuberance, this was a primary argument: we’re leaving the job undone in Afghanistan to launch off on a new adventure that has nothing to do with the threat we are trying to defend against. This argument was both deeply accurate while also being very much captive of the thinking of the time.

Nor did it end there.

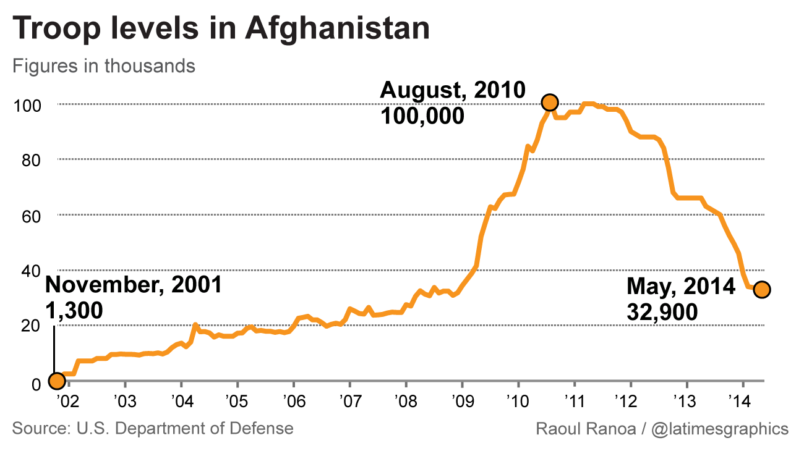

In looking at the history of President Biden’s aversion to the US garrisoning of Afghanistan, I’ve repeatedly mentioned his experience watching then-President Obama get rolled by the Pentagon into supporting the Afghanistan “surge” during his first term. Biden opposed it; Obama was convinced. It’s worth remembering how massive a decision this was. Through 2002 and 2003 there were scarcely more than 10,000 US and NATO troops in Afghanistan. Over the course of Bush’s presidency that number crept up toward around 30,000. In 2010/2011 ‘surge’ era that number reached as high as almost 100,000. This LA Times infographic captures the story through through 2014 …

But Obama’s decision didn’t come out of the blue. In 2008 Obama actually ran on ending the US occupation of Iraq – you remember that part – but also intensifying the US presence in Afghanistan. In part this was a bit of positioning: Obama was seeking to inoculate himself against attacks on being too weak-kneed a commander-in-chief over leaving Iraq by saying he’d get even tougher in Afghanistan, where after all the 9/11 attacks had originated. But it wasn’t only positioning. It also encapsulated what Democrats had been saying for years: the US lost its focus on Afghanistan because of its misplaced zeal to overthrow the government of Iraq.

In other posts over the last two weeks I’ve argued that a generation of writers, reporters, foreign policy hands, think tank denizens and more became deeply identified with these missions. We know that there are lots of people who are rah-rah war boosters and always want to bomb or topple whatever government has us pissed off. This isn’t that. These are people who look more fully at the costs of war, human and otherwise, who think seriously about what we are trying to accomplish as a country in these various engagements. They’re mostly not the people I quoted above saying, “Hey, empires were actually pretty awesome and now we know how to do it even better.” The old saw has it that if you have a hammer everything starts looking like a nail. And the 9/11 attacks triggered a generation in which America got into the hammer business, hammers for pounding things in the Middle East and Central Asia. People got very invested in that universe of questions, ambitions, aims. The collective press tantrum over the last few weeks, echoed in a certain part of official Washington suddenly punctured a broad ranging denial about the failure of these aspirations. And thus, here we are.