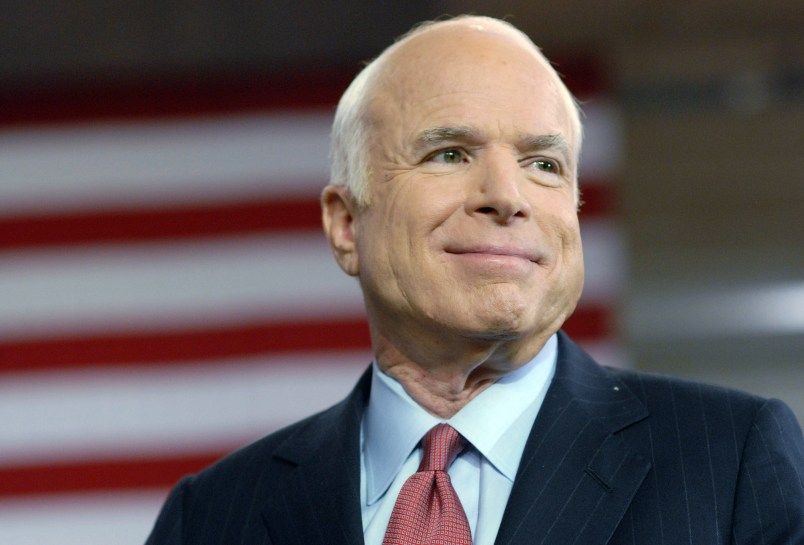

I don’t mean to add another obituary of John McCain, but only a footnote about an aspect of McCain’s background, character, and politics that the obituaries I’ve read has ignored. McCain was a member of America’s upper class and had the sensibility of a certain wing of that upper class. That’s important to understanding his contribution to American politics and his contempt for Donald Trump.

I am not referring to the upper class as an income group on a distributional chart. It’s a social class distinguished by a certain standing and sensibility. It has had its share of ministers ( the Coffins), writers (the Lowells), politicians (the Rockefellers), soldiers and academics as well as businessmen and bankers. It was originally limited to Anglo-Saxon Protestants, but has come to include Catholics (like the Kennedys) and now even Jews. Some members of the upper class, like the McCains, can trace their lineage back two centuries. Others went from new to old wealth in a century or even less. Sometimes, the children increase the family’s wealth; other times, they live off of it, or off the wealth of their wives.

Before the Civil War, the McCains were plantation owners in Mississippi, and after the Civil War bequeathed two generations of admirals and generals who handed down to John McCain an outlook that shaped his character and his politics. McCain’s grandfather and father were both four-star admirals. The sons came to their wealth by marriage. John McCain’s father married the daughter of a wealthy oilman; and John McCain’s second wife, Cindy Hensley, was the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in Arizona who originally made his money as a beer distributor.

There is, of course, not one single outlook that defines the American upper class, but there is an important strain that dates from the late 19th century and that very much fits McCain. It features an ethic of public service and of putting country before self; a feeling of responsibility toward the less fortunate, or noblesse oblige; high-mindedness and contempt toward corruption in business or government; a disdain for the conspicuous display of wealth or religiosity; and a determination, especially among male descendants, to make it on their own. George H.W. Bush, for instance, the son of a senator, who was the son of a steel executive, was a war hero, moved to Texas to make it on his own as an oil man (connections and funding aside) and having established himself in business, devoted the rest of his life to public service.

McCain perfectly fit this pattern. His soldierly preoccupation with honor and putting country before himself; his crusade against political corruption (which was spurred by his peripheral involvement in the Keating scandal in 1989); his unwillingness to join his party’s various assaults on the poor and defenseless – shown most recently in his refusal to repeal Obamacare; his distance from big business Republicanism and the religious right (both of which were most clearly on display in his 2000 campaign). McCain would have seen Trump as the antithesis of everything that this upper class ideal stood for: the flaunting of ill-gained wealth; the dishonesty and corruption; the preoccupation with self; the bigotry and rejection of any genuine concern for the less fortunate.

McCain was not initially familiar with Theodore Roosevelt’s story. He learned about Roosevelt from his aide Marshall Wittman, an advocate of “Bull Moose Republicanism,” during the 1990s.

McCain found echoes of his own past and principles in Roosevelt. Roosevelt, the son of a businessman and government official, had sought to make it on his own as a Western rancher and as an author. His ideal was that of the self-less courageous warrior, whether in combat, when he served in the Spanish-American War, or as a politician, where he sought forthrightly to put the nation’s interest first. In an essay in 1900 on “The American Boy,” Roosevelt tried to combine the ideal of soldier and politician:

A boy needs both physical and moral courage. Neither can take the place of the other. When boys become men they will find out that there are some soldiers very brave in the field who have proved timid and worthless as politicians, and some politicians who show an entire readiness to take chances and assume responsibilities in civil affairs, but who lack the fighting edge when opposed to physical danger. In each case, with soldiers and politicians alike, there is but half a virtue. The possession of the courage of the soldier does not excuse the lack of courage in the statesman and, even less does the possession of the courage of the statesman excuse shrinking on the field of battle.

McCain became enchanted with Roosevelt’s words and example. His 2000 campaign echoed Roosevelt’s maverick campaign in 1912 as the candidate of the Progressive Party. It’s not easily remembered now, but McCain condemned George W. Bush’s proposals for favoring the rich.

But McCain was also inspired by his reading of Roosevelt, and by his acquaintance with two other TR fans, William Kristol and Robert Kagan, to move from a cautious realism in foreign policy to an expansive form of American neo-imperialism. Roosevelt the progressive was also the proponent of American expansion overseas. He was principally responsible for an invasion of the Philippines that led to a fourteen-year war. McCain became the leading Senate proponent of an invasion of Iraq. In his last two decades, McCain combined a passionate embrace of an American ideal of democracy and human rights with a willingness, when all else failed, to send in the troops. In 2008, for instance, he wanted to send NATO troops into Georgia on Russia’s border. He rejected the Obama administration’s attempts to withdraw troops from Iraq and Afghanistan.

As a member of America’s upper class, McCain inherited a commitment to honor and country and disdain for corrupt arrivistes like Trump; he also inherited a propensity to seek solutions by force of arms that led him to embrace policies that were very much not in the country’s interests. It’s hard to separate the two, but in the wake of his death, it’s worth doing so. The McCain of honor and noblesse oblige was a blessing to American politics. It is what he had in common with the Roosevelts, the Kennedys, George H.W. Bush, John Kerry and other scions of the upper class. You don’t have to be rich and famous and fancily educated and raised to be of service to American politics, but if you are, it’s better you be like them than like a Trump or Koch.