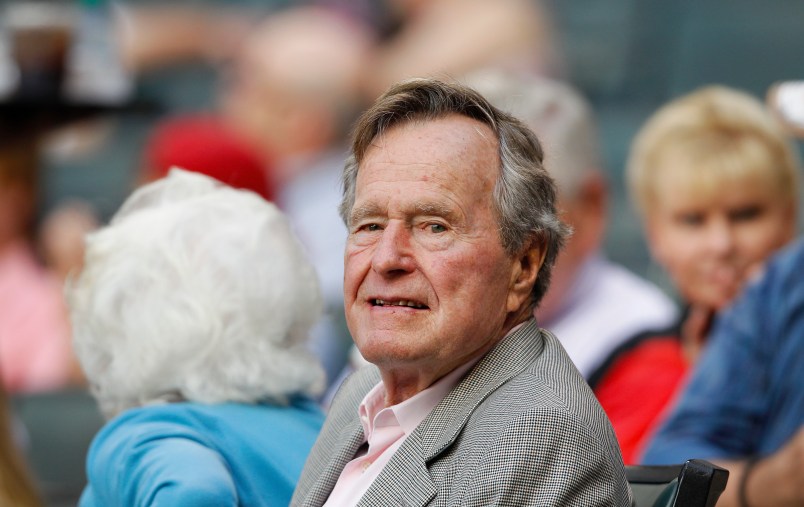

George H.W. Bush’s death, like that of John McCain, has brought forth glowing tributes that are veiled critiques of our current president. In response, some commentators on the left have pointed to Bush’s flaws and failures – from his rejection of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to the Willie Horton ad in the 1988 campaign and from the Iran-Contra scandal (of which he was an unnamed conspirator) to his tacit acceptance of the Tiananmen Square massacre. I want to sidestep this debate to say something 80 percent positive about one aspect of Bush’s foreign policy that most clearly came to the fore in his dealings with Europe, the Soviet Union and the Middle East.

Bush and his two top foreign policy advisors – Secretary of State James Baker and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft – were realists. I don’t mean this in the academic sense. They didn’t believe that countries’ mode of government is irrelevant to their foreign relations. What they had was a realistic appraisal of what America could accomplish in foreign policy and of the kind of change other nations were willing to accept. Unlike many liberals and neo-conservatives, they didn’t believe that the United States could transform the world into liberal capitalist democracies.

Managing the Cold War’s End: Bush and Baker deservedly get credit for negotiating with Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Union for the reunification of Germany. During these negotiations in February 1990, Baker promised not to expand NATO eastward. Baker told Gorbachev and Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze that if they agreed to the reunification of Germany, “there will be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction or NATO’s forces one inch to the East,” NATO’s precipitous expansion, initiated under and championed by Bill Clinton and by a neo-conservative lobby led by a former Lockheed executive, planted the seeds for the revival of an older Russian nationalism and for our current conflict with Russia and Vladimir Putin.

Bush and Baker were widely criticized for balking at the dissolution of the Soviet Union (In Bush’s famous “Chicken Kiev” speech, he warned the Ukrainians of replacing “a far off tyranny with a local despotism.”) Bush also objected to German recognition in 1991 of Croatia and Slovenia, which began the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. Bush cannot be credited with a viable alternative, but in both cases, he saw clearly the danger of conflict and war where others did not.

The Middle East: Controversy still rages over whether Baker through April Glaspie gave Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein tacit assurance that the U.S. would not intervene if he invaded Kuwait.. Whatever the case, Bush was right to resist the Iraqi takeover of Kuwait. Sure it was about the control of oil, but a central purpose of the United Nations was to prevent large nations from taking over smaller ones, which had been a cause of war for millennia. Perhaps, the US could have avoided military intervention and stuck with sanctions. But Saddam had not budged after months of sanctions, and sanctions have a mixed record. At the UN, Baker also assembled an exemplary coalition to oust Iraq.

After the war was over, and Iraq was driven out of Kuwait, Bush was widely criticized by neo-conservatives for not moving onto Baghdad and ousting Saddam. There was ground for criticizing Bush for inspiring a Shi’ite rebellion and then standing by while Saddam later slaughtered them. The U.S. might have stopped Saddam without moving onto Baghdad to oust him, but Bush was worried that any further offensive could topple him and unleash chaos. Bush stated his reasoning in A World Transformed, which he wrote with Scowcroft in 1998. Marching on Baghdad, they wrote, “could plunge that part of the world into even greater instability and destroy the credibility we were working so hard to establish.” There were, of course, prophetic words.

Finally, Bush, Baker and Scowcroft recognized that in order to establish a more stable Middle East, they would have to bring the Israelis and Palestinians to the negotiating table. The conflict wouldn’t just go away and the United States could not continue to back Israel unequivocally. In the fall of 1991, the administration organized a conference in Madrid that was designed to bring Israelis and Palestinians together. Israel’s rightwing premier Yitzhak Shamir balked at sending representatives. In response, Bush held up $10 billion in loan guarantees to Israel and demanded a “settlement freeze.” He was attacked by AIPAC, the lobby for Israel, and by Democrats and Republicans alike. At the time, I heard Bush and Baker termed “anti-Semites.” But their pressure got the Israelis to the conference and laid the basis for the Oslo agreement, which was as close as the Israelis and Palestinians have ever come to resolving their differences.

Why, though, only 80 percent praise for these actions? That’s because Bush, Baker and Scowcroft didn’t seem to unequivocally back their own approach. In a recent study based of Bush and Baker’s negotiations with the Soviet Union in 1990, Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson has unearthed evidence that Bush and Baker were not being entirely candid in promising Gorbachev not to expand NATO. During the administration’s last two years, the possibility was considered. Bush and Baker’s actions at the UN in the aftermath of the Iraq War also set in motion the pattern of sanctions and stonewalling that led up to the American and British air attacks against Iraq, and laid the basis for the Iraq War. But these equivocations aside, Bush, Baker and Scowcroft displayed in their foreign policy in Europe and Middle East a realism that was noticeably lacking in their successors.

Bush’s successors had their own charmed moments – Clinton in the Balkans, George W. Bush’s initial intervention in Afghanistan, and Obama’s Iran deal – but they became enamored with idea of transforming the world in America’s image.

Bill Clinton, for instance, thought that bringing China into the World Trade Organization would move it toward democracy and market capitalism. While Bush’s National Security Council debated, but did not endorse expanding NATO eastward, Clinton vigorously promoted the expansion of NATO over the objections of the country’s main Russia experts, led by George Kennan. Clinton also signed the Iraq Liberation Act, which neo-conservatives later cited as a justification for war.

George W. Bush did the most damage to the county’s foreign affairs of any president in my lifetime. It wasn’t just the war in Iraq. Well before Trump, Bush abandoned any attempt to reach an international agreement on climate change. And Obama suffered from the utopian fantasies unleashed by the Arab Spring that led to the administration’s intervention in Libya and to its belief that even without concerted intervention, regime change in Syria was imminent. Trump, of course, has laid claim to some degree of realism about America’s ability to change the world. But Trump, like former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, seems to endorse the very dark side of realism: that while he has forgone attempts to transform the world into liberal capitalist democracies, Trump actually seemed to encourage illiberal autocracies in Saudi Arabia or North Korea. His is not a sensible realism, but the negation of whatever is positive and important in America’s democratic idealism. If Trump had been in charge in 1990, Iraq might have been able to buy Trump’s acquiescence in its conquest of Kuwait.