A lot of people, including me, were misled by opinion polls into thinking that Democrats would make out like bandits in this election the way they did in 2018. As the “blue wave” has receded, many Democrats have gone to the opposite extreme and pronounced that outside of getting rid of Trump, the election must be counted as a failure. My own view is that the Democrats did about as well as could be expected given the political divisions in the country.

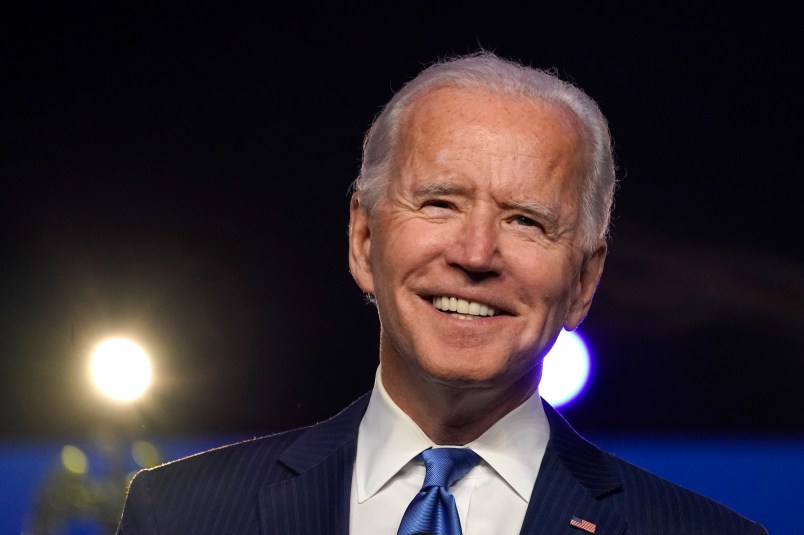

Start of course with Joe Biden’s defeat of Donald Trump. We are no longer, in the words of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, “in a free fall to hell anymore.” Biden’s victory also revealed Democratic inroads in the South and Southwest. And Biden won about 35 percent of the so-called white working class vote (and higher in Midwestern swing states), reversing the precipitous decline that began in 2010 and climaxed in 2016 when Hillary Clinton won a bare 29 percent of this vote.

In the Senate races — in a year where the geography was not particularly favorable to Democratic challengers — Democrats have already netted one seat, and could pick up one or two in Georgia’s special election on January 5. Biden’s victory showed that Democrats can win statewide votes there. In the House, Democrats will have lost a handful of seats they won in 2018 and came close to losing others, but they won a majority of House seats. I’d sum up these national races this way: since 1996, the Democrats and Republicans have enjoyed what Walter Dean Burnham called an “unstable equilibrium.” One party enjoyed temporary advantage over the other because of superior candidates and officials (or the contrary), circumstances (the pandemic), and superior organization (which, as the pro-Democratic labor movement has declined, was particularly important for Republicans in midterm and state and local races).

The greatest Republican disadvantage in 2020 (and in 2018) was Trump. Trump’s victory in 2016 was a fluke — the product on an opponent who ran a particularly inept campaign, the Comey letter, and voter fatigue with the same party having already controlled the White House for two terms. As president, Trump proved inept as a politician (making no attempt to reach beyond his fevered supporters), a policy-maker (deferring to Tea Party Republicans on health care and to business Republicans on taxes), and chief executive (bungling the response to the pandemic). In 2018, with a buoyant economy lifting them up, the Republicans should at worst have lost a few House seats, but Trump’s performance dragged them down. In this election, a less bilious Republican president who had pursued most of the same policies as Trump and handled the pandemic competently (like several northern Republican governors did) would have been re-elected.

Why did Democrats lose some seats in the House, but retain their majority? If you look at the particular elected Democrats who lost or almost lost seats, especially those in districts Trump had carried in 2016, they were hampered by the national party’s identification with demands to “defund the police” (which most Americans outside of a few zip codes saw as a threat to public safety), House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s failure either to achieve a deal on a stimulus bill or to make sure that the public blamed the Republicans for the failure, Biden’s threat to “shutdown” the economy in the face of the pandemic (which frightened Americans who are worried about losing or have already lost their jobs), the party’s support for a Green New Deal and opposition to fracking, and the specter of socialism (understood in South Florida as Cuban Communism and in other vulnerable districts as “socialized medicine.”)

Of these factors, I’d separate out those like defunding the police that arose from the extreme left during the protests over police brutality. No Democrat should support such a slogan as a national policy. I’d separate out, too, Pelosi’s mishandling (in my opinion) of the stimulus negotiations and Biden’s gaffe on “shutdowns,” which were mistakes of the moment. The other factors, such as Democrats support for a Green New Deal, Medicare for All (or in the case of this election, simply a public option) reflect differences of opinion within the broader electorate. Ocasio-Cortez insisted in an interview after the election that “sponsoring the Green New Deal was not a sinker.” Kendra Horn in Oklahoma and Xochitl Small Torres in New Mexico lost their seats and Conor Lamb in Western Pennsylvania almost lost his seat at least partly because of their party’s stand on fossil fuels.

The party’s support for strengthening and expanding the Affordable Care Act probably also hurt a few vulnerable Democrats. If you look at exit polls, you discover that 52 percent of Americans want the Supreme Court to protect the Affordable Care Act, but 43 percent want the court to throw it out. According to an NBC exit poll, opposition to the ACA is particularly concentrated in voters who make between $50,000 and $100,000. They oppose it by 53 to 43 percent, while voters who make less or more favor it. My guess is that many of these voters are mid-scale white and blue-collar wage-workers or very small business owners who make up the bulk of so-called white working class and have been moving to the Republican party over the last fifty years. They regard programs like the ACA as forcing them to pay taxes for the undeserving poor. Democrats can win these voters but it’s a hard sell. There have to be other overriding issues, such as presidential misbehavior, corruption and incompetence, the pursuit of an unpopular war, or policies that blatantly favor business at the expense of everyone else..

I’m not suggesting that the Democrats should give up on the ACA and public option or on phasing out fossil fuels (though as a long-term gradual, not an immediate, objective). These positions are also the reason why Democrats win House and Senate seats. In 2018, Republican attempts to repeal Obamacare (and deny insurance for those with pre-existing conditions) was a factor in Democrat wins. This November, in Georgia’s seventh district outside of Atlanta, Democrat Carolyn Boudreaux, who highlighted her support for strengthening the ACA, flipped a longstanding Republican seat. In Arizona, Mark Kelly won a Senate seat warning of the dangers of climate change. But Democrats (and Republicans) have to recognize that the country is divided on these questions and is going to remain so (alas!) with a Democratic President and a Republican Senate. That division underlies the unstable equilibrium between the parties.

A lot has been made of Trump’s increased support from Hispanics — which appears surprising given his nativist rants against illegal immigrants. Hispanics, like Asians, are a mixed bag of separate nationalities and cultures. In South Florida, Biden and two Democratic House incumbents who were defeated lost the vote of immigrants from Cuba, Venezuela and Colombia because of Trump’s outspoken opposition to Cuban and Venezuelan socialism or communism. But Democrats also lost some voters in the Southwest among immigrants and their descendants from Mexico and Central America. I would conjecture (and I can’t do any more than that confined to my quarters in Silver Spring) that there were factors that led some Hispanics to back Trump and Republicans.

The first was the Democrats’ embrace of abortion, gay marriage, and among some very leftwing Democrats extreme stands on gender. Many Hispanics are observant Catholics or evangelical Protestants: many are anti-abortion, leery of gay marriage; many would find the discussions of transgender rights and the abolition of gender classifications incomprehensible. They will vote for a pro-choice Democrat as long as the candidate doesn’t trumpet their support for abortion, but they will balk at someone like abortion rights champion Wendy Davis, who lost Hispanic counties and only got 56 of the Hispanic when she ran for governor of Texas in 2014 against a rightwing Republican.

The second factor was economics and education. Hispanics seem to be making the same political journey, if at a slower pace, that other older immigrant groups have made. Working class Hispanics vote Democratic because of jobs and benefits. As they move up the lander economically and by education, they come to share Republican concerns about taxes and spending. According to the Latino Decisions’ election polling, Trump’s support among Hispanics in this election seemed to rise with education and income. Unbeknownst to most Democrats in Washington, Hispanics are not preoccupied with where a politician stands on immigration. They favor comprehensive reform, but oppose open borders. And in this election, they were primarily worried about the pandemic and about jobs.

Over the last decade, some Democratic consultants and activists have promoted the idea of a majority-minority. In so far as minorities have disproportionately favored Democrats in the past, they reason that as “non-white” minorities became a majority of the population in a decade or so, Democrats will enjoy an enduring political majority. It’s not only bad political science given the complexity of the Hispanic vote; it’s also bad demography. As sociologist Richard Alba has shown, many Hispanics (who are the single largest group of minorities) intermarry with whites and have children who identify themselves as “white.” They don’t think, “I am a Hispanic and therefore must vote Democratic.” Alba estimates that a majority of Americans will identify as “whites” well into this century. That doesn’t mean that Americans with Hispanic ancestry won’t support Democrats; it means that if they do, they won’t necessarily do so because they have Hispanic ancestors.

To sum up: We are a divided country politically, and the results in 2020 reaffirm that. Democrats, on the average, did better than Republicans in 2018 and 2020 because of the unpopularity and ineptitude of Donald Trump and probably, too, because of Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Joe Biden, Nancy Pelosi, and Chuck Schumer will face formidable obstacles in preventing Republicans from winning back the House in 2022 and the Presidency in 2024. They are going to have to either pass a huge stimulus bill that will abet a recovery or make sure (as Barack Obama failed to do in 2009-10) that the public blames the Republicans for the failure. Many of the other things Democrats have to do — from reinstating policies on climate change to giving labor unions a better chance to organize — Biden will have to do that through the executive branch without help from Congress. Will Biden be up to it? One hopes.