Months after my father died unexpectedly in 2006 I had most of his belongings shipped to me in New York where I had them delivered to a storage unit several blocks from my home. Most of my father’s possessions, at least the ones that mattered most to me, were his archive of tens of thousands of photographs and his collection of cameras, the ones he used — SLRs, TLRs and various large format cameras — as well as a large collection of antique cameras. I went to check on everything shortly after it was delivered. There it was, in standard moving boxes, packed into a 5 by 10 foot space. I took a few albums of photos and left the rest there for 15 years.

Until last week.

Why did I wait 15 years? The standard reasons, more or less. Starting with the practical and mundane, I simply had no room to store or keep more than a fraction of it. So I had little choice but to leave it there. And as long as everything was packed in those boxes, with the boxes packed tightly in the larger corrugated aluminum box which was the storage unit, the contents were basically inaccessible. Even if I’d had the space, the prospect of unloading and processing everything was overwhelming, both logistically and emotionally.

My father was a marine botanist. But in early mid-life he transitioned into photography. For much of the 1970s and 1980s he was shooting a roll of film every day or two — virtually all of it was Tri-X, Kodachrome and an ill-fated 1970s era film stock called 5247. The precise volume and rate may be clouded by the impressionistic nature of childhood memory. But the boxes upon boxes of archival binders with contact sheets, negatives and slides confirm the essence of the story.

Some of these photos were portraits. Some were his experiments working in the visual idioms of heroes of his like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. But mostly they were just of daily life — his wife, his son, his daughter and everything else. Today we’re awash in photographs. We take pictures of our food, countless selfies, random things through the day. If we’re taking a picture we may take half a dozen to just to have several to choose from. By one estimate, starting in 2015, more pictures are taken in a single year than in the entire 150 year history of film photography. But there was nothing remotely like that in the 1970s and 1980s. Taking pictures cost money. There was no immediate gratification since they had to be sent away to be developed and printed. Partly he could do this because he could and did develop his own film and print his own photographs, especially his work in black and white. He not only took them but saved them. All of them. I assume there are very few people my age whose childhood is as extensively photographed as mine.

Now, in my early 50s, I finally have sufficient room to begin working my way through my father’s belongings and much of the remaining arcana of the first two decades of my life. So last Friday I rented a U-Haul truck and with my two teenaged sons made an early start of it. We cleared out the storage unit, piled the boxes in the truck and brought them home.

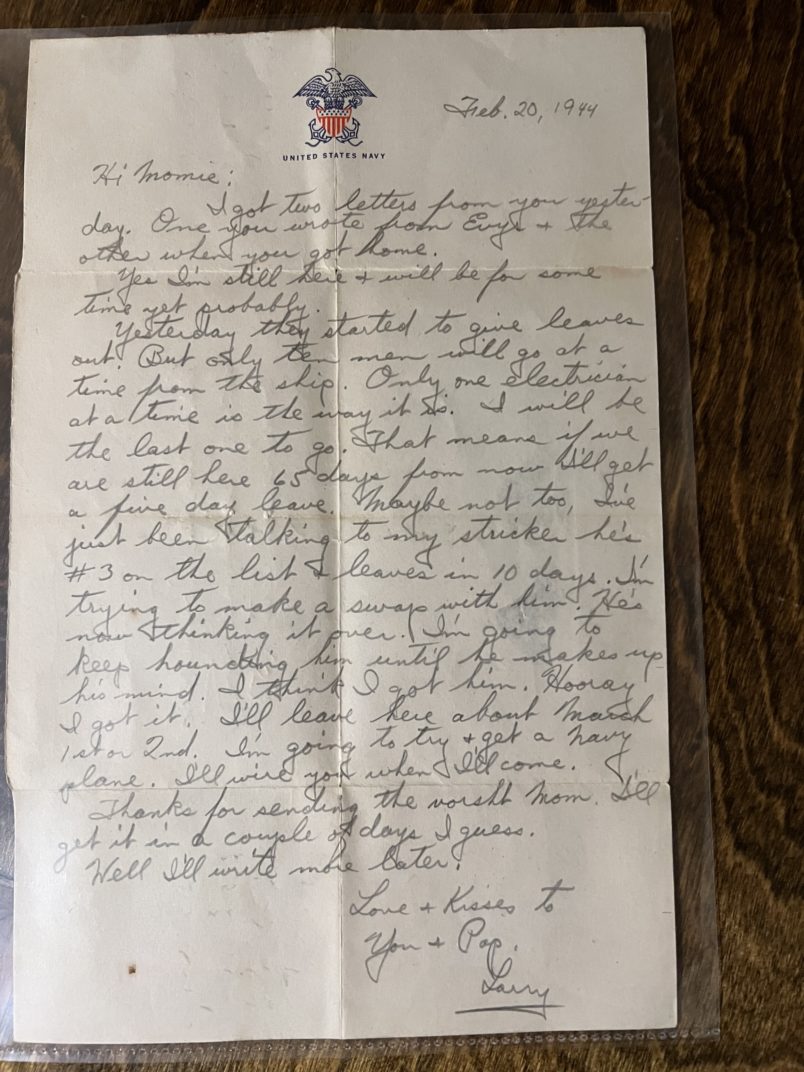

Over the weekend I began my initial reconnaissance into these boxes. The bulk of what is there, I think, falls into three broad categories: the negatives and photographs, the cameras and the kit for a late 20th century darkroom. The negatives and photographs are a sort of patrimony which I plan to organize and preserve for the rest of my life. I will keep a small number of the cameras which have particular sentimental or historical value and sell or give away the rest. The darkroom equipment I will simply sell or dispose of. It has no real meaning to me. But of course there are other small details and effects of a life. As I was cutting open boxes for a first look I found a small greyish blue case, what almost looked like a tiny suitcase with old-fashioned flap down latches and steel reinforced corners — the kind of piece that certainly hasn’t been made in the last half century at least. It contained the letters my father’s uncle, Larry, sent home while serving in the Navy during World War II. I already own some of his service medals, his Purple Heart, various military papers, the set of playing cards he bought in Sweden during a port call. This was clearly the place his letters were kept as they arrived, tightly folded, largely intact, carefully preserved.

Looking at the case and the disposition of the letters I suspect most had been folded more or less as I found them since they were first read almost 80 years ago, though a smattering of the documents had been added in subsequent years, one as recently as 1990. Today I began opening and unfolding these letters and envelopes, Air Mail letters in which the envelope is the letter itself inside out. As we do in history, one pieces together the story comparing memory and first person accounts with physical artifacts. Though these were among my father’s belongings I’m pretty sure this was the box I remember my grandmother kept in the cabinet in the bureau in her living room which her TV sat on top of. If I go deeper, piecing together childhood memories and other knowledge of the people in question I’m pretty confident it was originally in the possession of her mother, Sadie Rosenberg, my great grandmother who I briefly knew in the final years of her life in the early 1970s. The letters are new to me but also distantly familiar. There are one or two letters in that cache of artifacts I noted above, which I have read as an adult. I may have seen some of these as a child.

The key to this story is that these are the letters of a doomed young man. Larry Rosenberg was a Navy Master Electrician who served on a Buckley-class destroyer escort called the USS Fechteler (DE-157), which was launched in April 1943 and sunk by a German U-boat in May 1944. The Fechteler’s job was to escort ship convoys, to hunt submarines and protect convoys from their attacks. Her most common missions were on the convoy routes bringing oil tankers loaded at refineries off the northern coast of South America through New York and on to combat operations in North Africa and Europe. On April 1st, 1944 the Fechteler sailed out of New York for Hampton Roads, Virginia where it joined a convoy bound for Bizerte, Tunisia. On its return journey it was torpedoed by a German U-Boat near Oran, Algeria. The Fechteler broke in two and sank. 186 of the 215 officers and men on board were picked up by USS Laning and other nearby ships. Larry Rosenberg was one of the 29 men who went down with the Fechteler. He was 25.

This fact colors everything in every letter he wrote during the final two years of his life: updates on what he is doing with his time, various shore liberties around the Atlantic and Mediterranean, girls he met or whatever he was ready to share with his mother, reassurance that he’s okay, plans he’s making for his life after the war. Of course I never knew Larry Rosenberg. He died twenty five years before I was born. But I knew people who did know him. So I knew the shattered intimacy his short life left in its wake.

The Fechteler sank a few weeks before my father’s sixth birthday. So he had only vague recollections of his uncle. But he was my grandmother Sophy’s little brother, six years younger. Decades after he died, as an old woman, she would grimace recounting details of his life which inevitably settled on to his violent and time-cheated death. I remember the clenching face and the way the conversations would trail off with her shaking her head. A rift later developed between Sophy and her older, fancier sister Evie. From a Scandinavian port call Larry had sent each sister of bottle of liquor they would share when he returned. Sophy never opened hers; Evie eventually did. To Sophy it was a betrayal. She told me the story when I was a small boy. They patched up their differences late in life. But I don’t think Sophy ever forgave it.

My father had some of this hurt. But his grief was really the imprint of his mother’s grief on him. And that pattern stepped back through the generations. As it was later recounted to me, Sadie never really recovered from her son’s death. Since he went down with his ship, there was no body. Sailors unaccounted for after a ship goes down begin as missing in action and then later are declared dead on the basis of logic rather than a body. A shipmate told Larry’s parents, based on the details he knew, that he believed Larry, a Master Electrician belowdecks near the site of impact, was likely killed in the initial torpedo impact or drowned in the immediate resulting cataclysm. But the lack of a body or any precise knowledge of what happened allowed Sadie to indulge for years in half-believed fantasies that he might have survived on some deserted island, yet to be found alive. My grandmother Sophy’s recollections often ended with Sadie’s inability to let go. Sadie’s grief was imprinted on Sophy.

291,557 Americans died in combat in World War II, virtually all of them young men. We know this from history books. Movies are still produced dramatizing these men’s deaths going on a century later. But in the American collective memory the reality and impact of these deaths are somehow muted, softened by America’s unparalleled victory and the war’s continued prominence in public memory. Even today most of the building blocks of the world we live in are ones put in place in the aftermath of that conflict. There were evil powers. America vanquished them. There followed a broad and unparalleled prosperity which in many ways continues right down to today. If one must die surely this is the kind of heroic effort to die in. If this is an idealized and incomplete version of the story it contains enough truth to maintain a firm hold on our imaginations. But Larry Rosenberg’s death left only a vast hole in his family, a never-healing wound which echoed down through generations. These letters radiate an intact, perfectly preserved grief, one not smoothed or stitched back together by any pride in sacrifice and without any sense of completion to it. They are like doors into a world of anguish and loss one never returns from. No one was able to reweave this story into a tale that pointed, albeit under the weight of great sadness, toward a recognizable future or one of new possibilities. It was simply an end, like a road going off into the distance which simply ends, with no logic or reason or explanation, asphalt and yellow lines and then dirt. A project cut short and never completed.

But there is an additional backdrop to this story. Probably most or all of these people would have died during World War II if not for decisions they and their parents and grandparents made in the two or three decades before War War I. The Rosenbergs and most of the rest of my family were part of a vast late 19th century migration of Jews from the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and German empires and the various ancient states and peoples they contained within them. These were people who threw everything in with America, a country that offered the promise not only of safety but a complete equality. Like so many families and ethnic communities that arrived as immigrants at the tail end of the 19th century — Italians, Poles, Greeks, South Slavs — participation in the Second World War served to seal their status as full participants in America.

As I was leafing through these letters I decided that they had rested long enough, bundled and folded, mostly inaccessible in this little grey-blue case. So I meticulously unfolded and ordered them in archival sleeves in the kind of three ring binder my father used for his negatives, slides and photographs. As I was working through each document I realized this was not only a collection of Larry’s letters but more like a small, portable shrine to his life. In addition to the Navy letters, there is a letter he seems to have written home from camp in 1931, age 12. His birth certificate is there, born May 7th, 1919, as is his Social Security card, issued in 1936, age 17. So is his High School diploma and a certification as an electrician. But one document doesn’t fit: his father, Nathan Rosenberg’s certificate of naturalization, issued in November 1944, some six months after his son died.

Is there some significance to this? Are the two events connected in some way? Or did this grey-blue case simply become a repository of important family documents, the certificate’s presence among the letters the result of a momentary, fortuitous decision seventy-some years ago? That last option seems possible but not likely. Having now reviewed every document in the case, this is the only one not directly connected to the life and death of Larry Rosenberg. What further draws my attention to this document is that by 1944 Nathan Rosenberg had been living in the United States for 46 years, since arriving at age 10 in 1898. (Sadie still shows up on the 1950 Census as a non-citizen.)

What changed at age 56 less than a year before the end of the war? A question for further investigation.

Members-Only Article

Members-Only Article