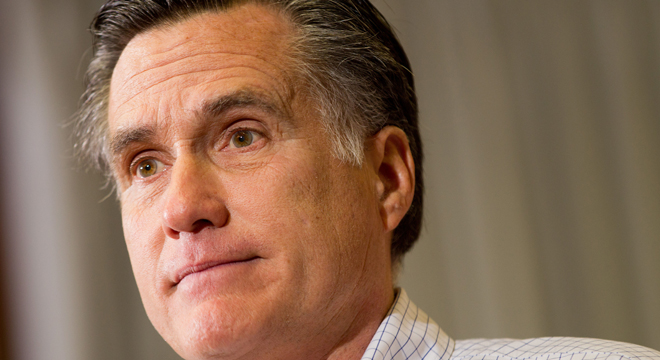

Mitt Romney still says he’s unlikely to publicly release his tax information, even if he clinches the Republican presidential nomination, and Democrats have a pretty good idea why.

Romney is a privileged poster child for the “Buffett Rule” — President Obama’s principle that the tax code should make it impossible for a person of great wealth to pay a lower share of their income in taxes than ordinary people. The DNC knows it, policy wonks know it, Romney certainly knows it. But the reasons why are technical and illustrate just how different Romney is from the vast majority of Americans who will cast votes for him — in either the GOP primary or the general election.

One tax expert told TPM of “fairly sophisticated tax strategies” that would be “not available to ordinary tax payers.” A technique that puts you in a position that’s “like having an unlimited 401k account” sounds very attractive. But maybe not if you’re running for office, for Pete’s sake.

When Romney jokes that he’s been unemployed for years, he’s obscuring the fact that he’s still collecting millions of dollars of investment income, which is taxed at a much lower rate than it would be if he, like most taxpayers, took home a regular paycheck. He’s also obscuring the fact a great deal of that same income is only vaguely connected to his own underlying investments, and yet benefits from a key loophole in the tax code that allows him and other wealthy finance veterans to more than halve their effective tax rate.

In private equity, fund managers are typically compensated with both a fee (two percent of assets) and substantial share (20 percent) of the fund’s profits. Those profits are called “carried interest” and they’re classified as long-term capital gains, which are taxed at 15 percent — much lower than wage income, on which the top marginal rate is 35 percent. But unlike the fund’s main investors, the manager typically doesn’t put up more than a nominal share of the fund’s actual capital. In other words, this so-called “carried interest loophole” allows private equity fund managers to treat the money they make in exchange for their labor as if it was a return on an investment — even though they haven’t made such an investment at all.

“They’re performing services to these funds, they’re not putting in their own money except to a nominal extent,” says Vic Fleishcer, a tax law professor at the University of Colorado. “When Mitt Romney was working at Bain he received a share of the profits from the Bain funds and continues to do so today and that’s all being taxed at the long-term capital gains rate.”

Among fund managers, “the capital interest is typically very small compared to their stake in the profit,” says one tax expert in Washington who represents private-equity clients. In other words, a fund manager might have a tiny stake in the investment he’s managing, but nonetheless recoup a great deal of its profit, and then pay very little in taxes on that profit. This loophole puts huge downward pressure on the the effective tax rate people like Romney pay.

Until recently, too, they were allowed to set up offshore corporations in places like the Cayman Islands, which allowed them to avoid paying U.S. taxes until they return the profits home.

“That allowed Romney to defer his income taxes until he repatriated his income to the U.S.,” Fleischer said. “It [was] like having an unlimited 401k account…. These kinds of techniques are not available to ordinary tax payers. Because of the nature of his work he’s able to take advantage of some fairly sophisticated tax strategies and that highlights how different he is from your normal tax payer.”

There’s nothing illegal here — it’s all on the level, and the tax code doesn’t technically reserve these benefits for rich people alone. But in practice, high net-worth tax payers are the only ones who can really avail themselves of them.

“Very high income people have lots of investible income and we have a tax system that is preferential to investment income,” says Clint Stretch, a top tax lawyer at Deloitte. “If you have capital gains or dividends, under current law they have a 15 percent rate, it’s going to be very hard to get your effective tax rate up as high as a comparably wealthy wage earner…. If you layer on a group of high-income people who have tax exempt income — municipal bonds and so forth — it gets harder.”

In practice this means wealthy Americans can reduce their tax liabilities, and a lucky few in the investor class can really limit theirs.

“I looked at tax return data from 2008 and for taxpayers that earned more than half a million dollars — that’s six-tenths of one percent of all taxpayers — they had 72 percent of long-term capital gains,” Stretch said. “Taxpayers over $5 million had over 43 percent of capital gains…. That’s the magic of high income — and anybody with investments can do it, high income doctors and lawyers and accountants and celebrities and athletes can do it.” As Stretch notes, though, you can’t do it if you don’t have enough disposable income to make long-term investments.

Because the tax code is complex, and rife with benefits and deductions, it’s impossible to use Romney’s publicly available income figures to reverse engineer his particular tax burden exactly. But you can ballpark it pretty easily, as Michael Scherer at Time Magazine did way back in October.

In 2010 he and his wife made between $1.1 million and $2.8 million in royalties, salary, speaking fees and interest, most of which was likely taxed at a marginal rate of 35%, after accounting for deductions. The Romneys made an additional $5.5 million to $37.3 million from dividends and capital gains, which is generally taxed at a much lower rate of 15%….

Assuming that Romney declared roughly the same number of deductions as others in his income level and that his dividend and capital gains income qualified for the 15% bracket, Romney would have paid roughly 14% of his gross income in taxes to the federal government in 2010 according to Bob McIntyre, who crafts tax policy at the left-leaning Citizens for Tax Justice.

People who earn as much money as Romney typically make most of it in capital gains and often deduct more than they earn in royalties, salary and interest. In other words, they never pay the 35% rate that their income would be subject to if they just got a paycheck like most Americans.

That’s roughly the same as the effective tax rate for a married couple making $60,000 jointly.

On Romney, a Washington tax expert took a stab at it, “If I had to guess, you would find a very large charitable contribution deduction [based on Romney’s affiliation with the Mormon church] and then I’d think you’d see a lot of capital gains…. It’s likely to show a pretty low effective rate — but the same thing would happen if you saw Warren Buffett’s tax return.”