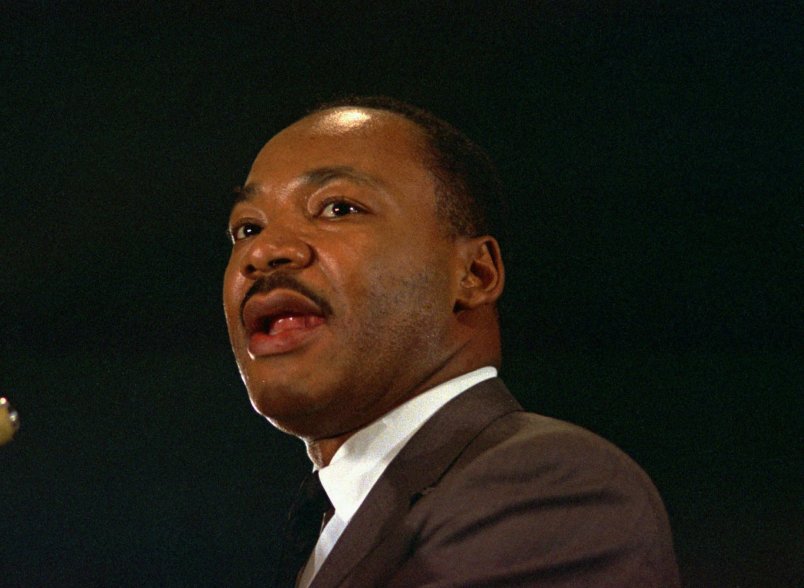

This Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, a film featuring Dr. King is making news. The recent controversy surrounding Ava DuVernay’s Selma has been the sense that it was snubbed in last week’s Academy Award nominees: The film received a Best Picture and Best Song nod, but no other nominations, with director DuVernay, star David Oyelowo, and screenwriter Paul Webb among those left out. People have made various arguments for why the film received so few nominations—from a relative lack of quality to an overall trend that saw no actors of color included among any of the 20 acting nominees—but it’s quite possible that the controversy over Selma’s portrayal of history contributed to the snubs.

A few weeks ago, just after the film’s initial release on Christmas, former Lyndon Johnson chief domestic aide Joseph A. Califano, Jr. wrote a scathing Washington Post op ed entitled “The movie Selma has a glaring flaw.” Califano’s argument, that the film distorts history in order to portray his boss as an opponent of the Selma marches and Dr. King, needs to be understood in the context of his role in and attachment to the Johnson administration. Yet in the subsequent weeks, many other figures, including historians and scholars of the era and the Civil Rights Movement, have likewise argued that the film portrays Johnson and his relationship with King as more adversarial than they were. Even if Johnson did not actually come up with the idea for Selma, as Califano argues, the scholarly consensus is that he was much less hostile to it than the film suggests.

Having seen Selma, I have to agree that it does distort history, making Johnson into more of a villain than seems justified by the historical record as it exists. And I believe doing so was a correct and necessary choice. For one thing, every prior Hollywood film about the Civil Rights Movement and era has used white characters as the lens through which to view African American histories and identities: from the FBI agents in Mississippi Burning to the lawyer in Ghosts of Mississippi, the housewives in The Long Walk Home and Fried Green Tomatoes to none other than Miss Daisy herself, time and again it has been through the perspective of white characters that these civil rights histories have been portrayed. And as a result, those histories have always been distorted, quite literally: viewed differently than they would be from African-American perspectives.

So by using African-American characters such as King and many other Selma leaders and marchers as its protagonists and perspectives, Selma likely, indeed inevitably, distorts other histories, such as those of the Johnson administration. Every work of historical fiction has to make such fundamental choices of emphasis and perspective, and in every case there will be benefits and limitations. What is perhaps so surprising about Selma for so many audiences and critics is that it has made a different choice from every prior civil rights feature film.

Moreover, in doing so, Selma does a much better job capturing the era’s deeper histories than any of those prior films. In the preface to her historical novel Hope Leslie (1826), which offered a stunning revision of existing histories of Native American and English encounters in Puritan New England, author Catharine Maria Sedgwick writes that her “design … was to illustrate not the history, but the character of the times.” That is, Sedgwick departed from the dominant public and official histories, imaging an alternative vision of the Puritan era. Historians have since discovered and confirmed that her historical fiction of events such as the Pequot War was indeed far more accurate than those prior histories.

I am not suggesting that our official histories of Johnson and the Civil Rights era are inaccurate, necessarily. But like the films that have viewed the movement through white perspectives, those histories are, when it comes to their portrayal of African-American identities and experiences, necessarily distorted by their choice and emphasis. And in Selma, we finally have a Hollywood feature film that distorts history in precisely the opposite direction—a long overdue, and very welcome, choice and effect.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

No. Though it may seem justified to distort history “in the opposite direction” to correct past perceptions, it’s a bad idea. This doesn’t correct the truth, it ghettoizes it. You can have your truth, and I can have mine, and everybody else is entitled to come up with some reason to bend truth their own way.

You would think that academics on the left would have learned the lessons of the excesses of multiculturalism and post-modernism. The people who today deny global warming and try to inject “intelligent design” and creationism into science curricula use the same arguments. The common refrain "I am not a scientist, but . . . " allows global warming deniers to reject the scientific framework in favor of their own personal truth.

History happened. It can never be precisely measured, but there is no acceptable excuse to distort it.

“History”, as has been noted by many, “is the propaganda of the victor.”

What benefit do we gain from any history that actively distorts reality to “make a point?”

Robert Caro’s magnificent (and still uncompleted) biography of Johnson is an exhaustive look at a man

filled with many contradictions, but a man who happened to be at the right place in history to achieve what no other

US politician had or could do…get effective Civil Rights legislation through a Congress fully controlled by its most fervent opponents.

Kennedy’s death, Johnson’s assumption of power, his encyclopedic knowledge of Congressional rules and the members of both houses, his awareness of his opponents weaknesses and needs…all were used to win passage.

Both King AND Johnson faced massive challenges and for King it included implacable and often violent resistance from supporters of segregation, rigged legal systems, and vigilantism, not to mention calls by many in the black community to fight back with counter violence.

I would argue that had Kennedy lived, he would not have been able to get a Civil Rights bill through Congress…at least not without the help of Johnson, who had been walled off from any meaningful input until Kennedy’s death. And without King, Johnson would not have had the actions which helped swing public opinion to “do the right thing,” finally…

Thanks for these comments. What I would stress in reply is the way I’m seeking to define (or re-define, given its general usage in such conversations) “distort”–to connect it back to the original sense, of how something looks different from one perspective than from another. From a Johnson-focused perspective, much of what dweb said seems quite accurate; from a King- and Selma-focused perspective, I would argue, Johnson was at best a reluctant accomplice in need of serious pushing and prodding, and to worst tied to Hoover’s FBI and the worst side of 1960s US government.

Ultimately, or rather cumulatively, the goal it seems to me is to get as full and rounded and comprehensive a picture of history as possible–which will never be precisely “what happened,” in some absolute sense, but rather that full picture. And so my main point here is that this film offers a very important new perspective that can help us move toward that full picture.

Thanks,

Ben

It’s hard to condense accurate history into a two hour movie. When the movie U-571 came out Jeremy Clarkson said “by the time the Americans captured an Enigma machine the Germans were practically giving them away.” I laughed and told my British friends “Well, you guys should’ve made the movie then.”

I saw Selma over the weekend and thought they did an excellent job of portraying the high drama of the three marches on the Edmund Pettus Bridge which was the focus of the movie. If I were to offer any criticism it was that they tried to be too accurate, they had to get a lot of characters in. For example they have to give Amelia Boynton some depth so the audience would care that she was laying unconscious on the bridge.

The difference between distortion because of the demands of the medium and distortion to serve an agenda is crucial. The first is unavoidable. The second does more harm than good.

Note that I haven’t seen the movie and am responding only to the argument presented in this piece.