This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

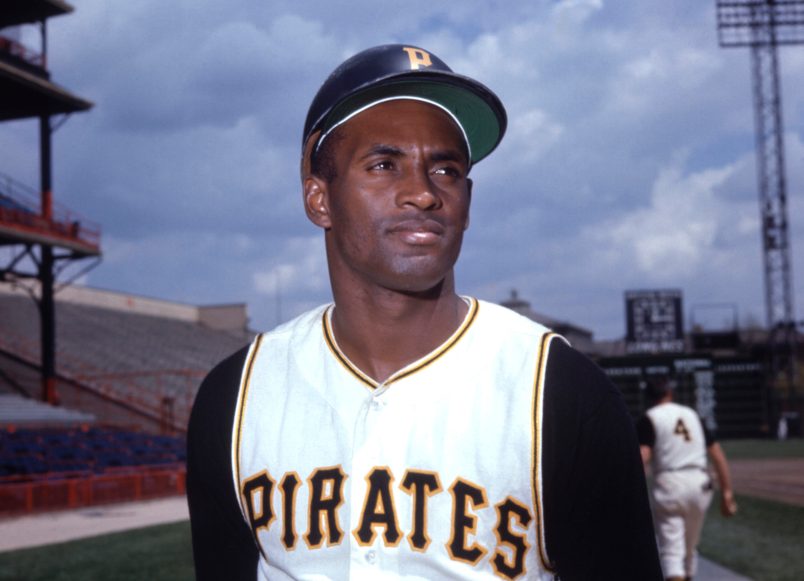

September 15 was not only the beginning of Hispanic Heritage Month but also Roberto Clemente Day. To honor the great Latino ballplayer, major league players wore his jersey number: 21. But the Tampa Bay Rays went further. On that day, for the first time in major league history, the Rays’ entire starting lineup was comprised of Latin American players – three from the Dominican Republic, two each from Venezuela and Cuba, and one each from Colombia and Mexico.

Clemente was not the first Latino to play major league baseball, but he was the first Latino superstar. He saw that as both a responsibility and an opportunity. Like Jackie Robinson, he used his athletic celebrity to speak out on behalf of social and racial justice. And like Robinson, he faced racism and pushback from owners, fans, sportswriters, and even some fellow players.

Clemente had an impressive 18-year major league career (1955-72), during which he played solely for the Pittsburgh Pirates. He played in 15 All-Star games, won four batting titles, was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1966, lead the Pirates to World Series championships in 1960 and 1971, reached 3,000 hits in his next-to-last game in 1972 (a feat surpassed by only 10 other major leaguers at the time), and had a lifetime batting average of .317, with 240 home runs, 1,305 RBIs, and 12 Gold Glove awards as best fielding outfielder.

Born in 1934 in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Clemente starred as an all-around athlete in high school. His arm was so strong that he became an Olympic prospect throwing the javelin. But he loved baseball and signed with the Dodgers in 1954, at a time when there were few Black and few Latino players on major league rosters. After one year in the minors, the Dodgers sold Clemente to the Pirates.

Clemente fought constantly against negative stereotypes, prevalent at the time, of emotional and lackadaisical Latinos. He bristled over the racist way that sportswriters covered him.

Sportswriters and baseball card companies called him Bobby or Bob, instead of his preferred name, Roberto, while white players were always asked what they wanted to be called. Writers made fun of his accent, quoted him in broken English, and paid little attention to his powerful intellect and social conscience. He knew little English when he joined the majors, and naturally spoke with a Spanish accent. After winning the 1961 All-Star Game for the National League, for example, Clemente was quoted as: “I get heet. … When I come to plate in lass eening … I say I ’ope that Weelhelm [Hoyt Wilhelm] peetch me outside. …”

In contrast, reporters routinely corrected grammatical mistakes in English for white players. Clemente refused to remain silent. He pushed back when a reporter called him a “chocolate-covered islander.” “You writers are all the same,” he shouted at one critical reporter. “You don’t know a damn thing about me.”

Clemente was frequently hurt and sometimes required surgery. He suffered damaged discs, bone chips, pulled muscles, a strained instep, a thigh hematoma, tonsillitis, malaria, stomach problems, and insomnia. Even so, between 1955 and 1972 he played more games than anyone in Pirates history. Yet some sportswriters, teammates, and managers repeatedly accused him of being lazy or faking injuries if he missed a game. To the contrary, Clemente repeatedly played through pain, and excelled nevertheless.

Clemente was a proud Black man, Puerto Rican, and American. From 1958 to 1964 he served in the Marine Corps Reserve. Coming from Puerto Rico, a more racially integrated island, he was shocked by the segregation he encountered in mainland America, especially during spring training in the Jim Crow South. Black players on the Pirates during Florida spring training in the late 1950s and early 1960s couldn’t stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as their white teammates. While on the road, white teammates had to bring Black players’ food out to the team bus. Clemente refused to sit and wait on the bus. He demanded that the Pirates provide Black players with another vehicle so they could drive to Black restaurants where they would be served. He and other Black players were also excluded from the Pirates’ annual spring golf tournament at a local country club, while their white teammates participated.

Even some of his teammates used racial slurs when referring to Clemente and other Latino players. Clemente pushed the Pirates to hire more players of color. By the early 1970s, half the team’s roster was Black, Latino, or Spanish-speaking, and in 1971, for the first time in major league history, the Pirates fielded an all-Black and Latino lineup, thanks largely to Clemente.

Clemente played during the peak of civil-rights activism. He closely followed the movement and identified with its struggles. He witnessed a speech Martin Luther King Jr. gave at a Puerto Rican university in 1962. They later became friends and met often, including a long visit on Clemente’s farm in Puerto Rico, where they discussed King’s philosophy of nonviolence and racial integration. Clemente voiced these ideas both inside and outside the clubhouse. As teammate Al Oliver recalled: “Our conversations always stemmed around people from all walks of life being able to get along. He had a problem with people who treated you differently because of where you were from, your nationality, your color. Also, poor people, how they were treated.”

After King was assassinated in Memphis on Thursday, April 4, 1968, Baseball Commissioner William Eckert announced that each team could decide for itself whether it would play games scheduled for the day of King’s funeral. On Friday, the next to last day of spring training, the Pirates’ 11 Black players (six of them also Latino) met at their hotel and agreed that they would refuse to play on Opening Day and the following day, when America would be watching or listening to King’s funeral. The following day, all 25 Pirates met at the ballpark and, after Clemente spoke, agreed to boycott their first two games.

Clemente and Dave Wickersham, a white pitcher, contacted Pirates general manager Joe Brown and asked him to postpone the season’s first two games or else the players would refuse to play. Then they wrote a public statement on behalf of their teammates that was published in the Pittsburgh Press the next day. They wrote: “We are doing this because we (white and black players) respect what Dr. King has done for mankind. Dr. King was not only concerned with Negroes or whites but also poor people. We owe this gesture to his memory and his ideals.”

The idea spread and players on other teams followed their lead. Commissioner Eckert, his back against the wall, reluctantly moved all Opening Day games to April 10. No sportswriter at the time described the players’ action as a strike. But that’s what it was – a two-day walkout or wildcat strike, not over salaries and pensions, but over social justice.

In 1969, Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood asked the Mayor League Baseball Players Association to support his lawsuit challenging the reserve clause, baseball’s version of indentured servitude, which made players properties of their teams. They could be traded to another team against their will, which is what happened to Flood. At Clemente’s urging, the players union held its annual executive committee meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Some players were skeptical about Flood’s lawsuit, but the tide turned after Clemente spoke out on Flood’s behalf. He declared that Flood was the only player with the courage to take on the owners and the reserve clause. “So far, no one is doing anything,” he said. The players voted unanimously to back Flood’s lawsuit.

Clemente’s activism went beyond fighting against racism and for players’ rights. Besides sponsoring philanthropies to distribute food, medical supplies, and baseball equipment, Clemente routinely visited sick kids in hospitals and held frequent baseball clinics for low-income children. He campaigned to use sports to counter drug problems in Puerto Rico and elsewhere. Most ambitiously, he began building a Sports City in Puerto Rico, seeking to replicate it throughout the United States to provide athletics and counseling but also intercity and interracial exchanges to challenge all forms of discrimination.

During the 1963-64 offseason, Clemente developed a lasting bond with the Nicaraguan people when he played winter ball for the Senadores de San Juan, who represented Puerto Rico in the International Series in Managua, the country’s capital. Clemente became a fan favorite during the series, making many friends and pledging to return.

On December 23, 1972, a massive earthquake devastated Managua. Over 7,000 people died, and thousands of others were injured. More than 250,000 people were left homeless. Back home in Puerto Rico, Clemente decided to help the recovery, using the media to organize a massive campaign of food, clothing, and medical assistance. Funded by Clemente, two cargo planes and a freighter began delivering the aid.

But Clemente found out that the U.S.-backed Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Jr. was siphoning off the international aid flowing into Managua (including $30 million from the United States) and stockpiling it for his corrupt government. For example, when a private American medical team arrived in Managua, it had to fight local Somoza officials from confiscating the supplies it brought. President Richard Nixon dispatched a battalion of US paratroopers to Managua, which only further helped Somoza loot the country. Nixon claimed he didn’t want the earthquake to provide opportunities for communists.

Clemente vowed to personally deliver the relief he had gathered. He believed that his presence would ensure that the aid would get to the people who needed it.

On December 31, 1972, the 38-year-old ballplayer boarded a broken-down and overloaded plane. Some warned him against making the trip, but he said, “Babies are dying. They need these supplies.” Several minutes after takeoff, the plane exploded and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, killing Clemente and four others.

The Pirates retired Clemente’s number in 1973 and the Baseball Writers Association of America waived the normal five-year waiting period to elect Clemente to the Baseball Hall of Fame that year; he became the first Latino player ever inducted. MLB established an annual Roberto Clemente Award (for community service) and Roberto Clemente Day. In 2002, President George W. Bush posthumously awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1974 the Roberto Clemente Sports City opened in Puerto Rico and has since served hundreds of thousands of kids, including future major league stars Juan González, Bernie Williams, and Iván Rodríguez. Clemente has been honored by dozens of schools, hospitals, coins, stamps, post offices, bridges, parks, housing developments, ballparks, streets, and museums in his name in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Nicaragua.

On Opening Day this year, Latinos (including U.S. players and those from Latin America) represented 28.5% of all players on major league rosters and 13% (four out of 30) of all big league managers.

Perhaps if Clemente were still alive, he’d be drawing attention to the Costa Rican factory that is partly owned by Major League Baseball and where workers toil under sweatshop conditions to manufacture all 1.2 million baseballs used during a major league seasons

Like Jackie Robinson, Clemente was an outstanding athlete and fierce competitor who used his celebrity to challenge baseball’s, and America’s, racism and to fight for better living and working conditions for everyone, regardless of race.

Clemente once observed: “If you have a chance to help others and fail to do so, you are wasting your time on this earth.”

Peter Dreier is professor of politics at Occidental College and co-author of the forthcoming Baseball Rebels: The Reformers and Radicals Who Shook Up the Game and Changed America.

Wow: Of course, I knew of Mr. Clemente, but this article has shown me that I really didn’t know much about him. An amazing man.

A truly outstanding person.

And this is the attitude more of humanity needs to embrace.

OT: Repost

Another great person…

OT: anyone who has ever heard him perform live knows he was a pure spirit. I saw him when he was about 70 years old but his power was all there to blow his horn. His most recent collaboration was with British electronic music wizard, Floating Points and the London Symphony. He always moved forward.

Jazz legend Pharoah Sanders dead at 81

Revered spiritual jazz saxophonist was known for his unique playing style and collaborations with John Coltrane

Excerpt

“He died peacefully surrounded by loving family and friends in Los Angeles earlier this morning. Always and forever the most beautiful human being, may he rest in peace.”

completely OT, but I am out of my mind upset about this

A Ducey appointed judge and our completely unlikable and asinine AG Brnovich have managed to make a law written in 1864 current law regarding abortion in AZ. Any healthcare provider who provides abortion or otherwise aids is subject to 2-5 years in jail. There are zero exceptions except for the life of the mother. As any medical person knows, that is a huge and easily disputed condition that will simply make sure most providers will do nothing even when the mother’s health is being threatened.

Excerpts

The basic provisions of the law were first codified by the first territorial Legislature of Arizona in 1864: It mandates two to five years in prison for anyone who provides an abortion or the means for an abortion. The state adopted the law with streamlined language in 1901; it remains on the books today as ARS 13-3603.

"We applaud the court for upholding the will of the legislature and providing clarity and uniformity on this important issue," Brnovich said in a statement Friday. "I have and will continue to protect the most vulnerable Arizonans."

Fun fact - when Brnovich talks about our most vulnerable Arizonans, he is not talking about poor women or people of color or undocumented aliens - he is talking about fetuses.

The 1864 law was in effect for much of Arizona’s history, and numerous doctors and amateur abortionists went to prison after convictions for violating it.

A companion law also adopted in the 19th century said a woman could face at least one year in prison for obtaining an abortion. That was repealed only last year, though it’s unclear if any woman served time for it. Congress granted statehood to Arizona in 1912.

As I have noted here before, my wife worked part time in an abortion clinic for a decade and a half (80s and 90s) through all of the craziness and violence of Operation Rescue. Many times I guided her through hostile and scary crowds of zealots to her job. To see what has just happened, I can only keep hoping that this will put some Democrats over the top here. It is discouraging right down to our souls, but maybe something positive will come of it.

The AZ Republicans are completely nuts here and unbelievably cruel in their piety.

OK. Clemente. Hero. Example.