This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

California is embarking on an audacious new climate plan that aims to eliminate the state’s greenhouse gas footprint by 2045, and, in the process, slash emissions far beyond its borders. The blueprint calls for massive transformations in industry, energy and transportation, as well as changes in institutions and human behaviors.

These transformations won’t be easy. Two years of developing the plan have exposed myriad challenges and tensions, including environmental justice, affordability and local rule.

For example, the San Francisco Fire Commission had prohibited batteries with more than 20 kilowatt-hours of power storage in homes, severely limiting the ability to store solar electricity from rooftop solar panels for all those times when the sun isn’t shining. More broadly, local opposition to new transmission lines, large-scale solar and wind facilities, substations for truck charging, and oil refinery conversions to produce renewable diesel will slow the transition.

I had a front row seat while the plan was prepared and vetted as a longtime board member of the California Air Resources Board, the state agency that oversees air pollution and climate control. And my chief contributor to this article, Rajinder Sahota, is deputy executive officer of the board, responsible for preparing the plan and navigating political land mines.

We believe California has a chance of succeeding, and in the process, showing the way for the rest of the world. In fact, most of the needed policies are already in place.

What happens in California has global reach

What California does matters far beyond state lines.

California is close to being the world’s fourth-largest economy and has a history of adopting environmental requirements that are imitated across the United States and the world. California has the most ambitious zero-emission requirements in the world for cars, trucks and buses; the most ambitious low-carbon fuel requirements; one of the largest carbon cap-and-trade programs; and the most aggressive requirements for renewable electricity.

In the U.S., through peculiarities in national air pollution law, other states have replicated many of California’s regulations and programs so they can race ahead of national policies. States can either follow federal vehicle emissions standards or California’s stricter rules. There is no third option. An increasing number of states now follow California.

So, even though California contributes less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, if it sets a high bar, its many technical, institutional and behavioral innovations will likely spread and be transformative.

What’s in the California blueprint

The new Scoping Plan lays out in considerable detail how California intends to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 48% below 1990 levels by 2030 and then achieve carbon neutrality by 2045.

It calls for a 94% reduction in petroleum use between 2022 and 2045 and an 86% reduction in total fossil fuel use. Overall, it would cut greenhouse gas emissions by 85% by 2045 relative to 1990 levels. The remaining 15% reduction would come from capturing carbon from the air and fossil fuel plants, and sequestering it below ground or in forests, vegetation and soils.

To achieve these goals, the plan calls for a 37-fold increase in on-road zero-emission vehicles, a sixfold increase in electrical appliances in residences, a fourfold increase in installed wind and solar generation capacity, and doubling total electricity generation to run it all. It also calls for ramping up hydrogen power and altering agriculture and forest management to reduce wildfires, sequester carbon dioxide and reduce fertilizer demand.

This is a massive undertaking, and it implies a massive transformation of many industries and activities.

Transportation: California’s No. 1 emitter

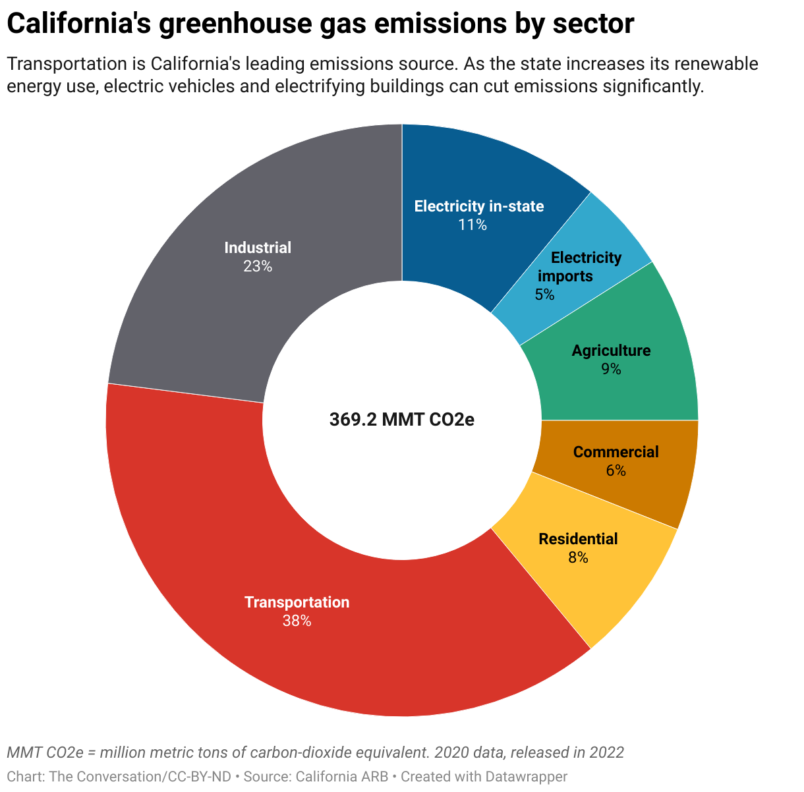

Transportation accounts for about half of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, including upstream oil refinery emissions. This is where the path forward is perhaps most settled.

The state has already adopted regulations requiring almost all new cars, trucks and buses to have zero emissions – new transit buses by 2029 and most truck sales and light-duty vehicle sales by 2035.

In addition, California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard requires oil companies to steadily reduce the carbon intensity of transportation fuels. This regulation aims to ensure that the liquid fuels needed for legacy cars and trucks still on the road after 2045 will be low-carbon biofuels.

But regulations can be modified and even rescinded if opposition swells. If battery costs do not resume their downward slide, if electric utilities and others lag in providing charging infrastructure, and if local opposition blocks new charging sites and grid upgrades, the state could be forced to slow its zero-emission vehicle requirements.

The plan also relies on changes in human behavior. For example, it calls for a 25% reduction in vehicle miles traveled in 2030 compared with 2019, which has far dimmer prospects. The only strategies likely to significantly reduce vehicle use are steep charges for road use and parking, a move few politicians or voters in the U.S. would support, and a massive increase in shared-ride automated vehicles, which are not likely to scale up for at least another 10 years. Additional charges for driving and parking raise concerns about affordability for low-income commuters.

Electricity and electrifying buildings

The key to cutting emissions in almost every sector is electricity powered by renewable energy.

Electrifying most everything means not just replacing most of the state’s natural gas power plants, but also expanding total electricity production – in this case doubling total generation and quadrupling renewable generation, in just 22 years.

That amount of expansion and investment is mind-boggling – and it is the single most important change for reaching net zero, since electric vehicles and appliances depend on the availability of renewable electricity to count as zero emissions.

Electrification of buildings is in the early stages in California, with requirements in place for new homes to have rooftop solar, and incentives and regulations adopted to replace natural gas use with heat pumps and electric appliances.

The biggest and most important challenge is accelerating renewable electricity generation – mostly wind and utility-scale solar. The state has laws in place requiring electricity to be 100% zero emissions by 2045 – up from 52% in 2021.

The plan to get there includes offshore wind power, which will require new technology – floating wind turbines. The federal government in December 2022 leased the first Pacific sites for offshore wind farms, with plans to power over 1.5 million homes. However, years of technical and regulatory work are still ahead.

For solar power, the plan focuses on large solar farms, which can scale up faster and at less cost than rooftop solar. The same week the new scoping plan was announced, California’s Public Utility Commission voted to significantly scale back how much homeowners are reimbursed for solar power they send to the grid, a policy known as net metering. The Public Utility Commission argues that because of how electricity rates are set, generous rooftop solar reimbursements have primarily benefited wealthier households while imposing higher electricity bills on others. It believes this new policy will be more equitable and create a more sustainable model.

Industry and the carbon capture challenge

Industry plays a smaller role, and the policies and strategies here are less refined.

The state’s carbon cap-and-trade program, designed to ratchet down total emissions while allowing individual companies some flexibility, will tighten its emissions limits.

But while cap-and-trade has been effective to date, in part by generating billions of dollars for programs and incentives to reduce emissions, its role may change as energy efficiency improves and additional rules and regulations are put in place to replace fossil fuels.

One of the greatest controversies throughout the Scoping Plan process is its reliance on carbon capture and sequestration, or CCS. The controversy is rooted in concern that CCS allows fossil fuel facilities to continue releasing pollution while only capturing the carbon dioxide emissions. These facilities are often in or near disadvantaged communities.

California’s chances of success

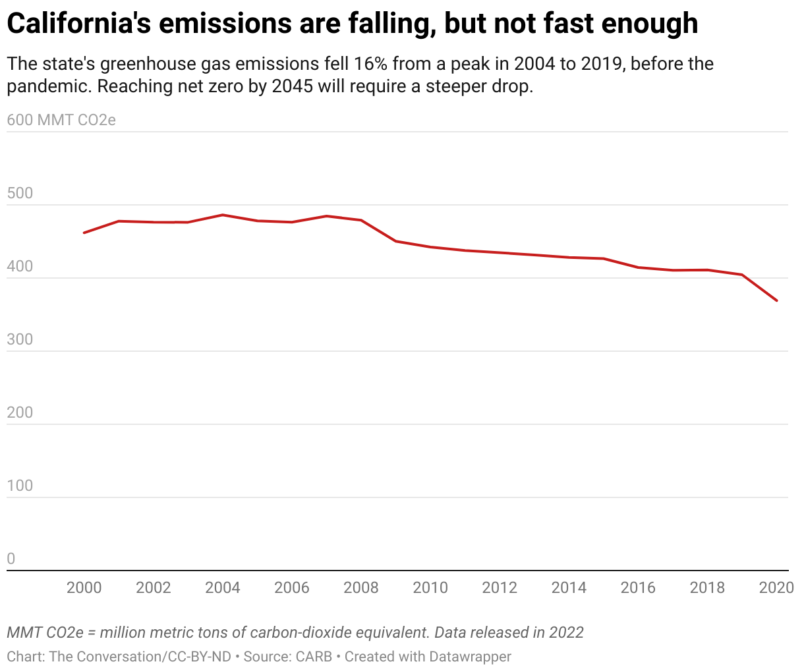

Will California make it? The state has a track record of exceeding its goals, but getting to net zero by 2045 requires a sharper downward trajectory than even California has seen before, and there are still many hurdles.

Environmental justice concerns about carbon capture and new industrial facilities, coupled with NIMBYism, could block many needed investments. And the possibility of sluggish economic growth could led to spending cuts and might exacerbate concerns about economic disruption and affordability.

There are also questions about prices and geopolitics. Will the upturn in battery costs in 2022 – due to geopolitical flare-ups, a lag in expanding the supply of critical materials, and the war in Ukraine – turn out to be a hiccup or a trend? Will electric utilities move fast enough in building the infrastructure and grid capacity needed to accommodate the projected growth in zero-emission cars and trucks?

It is encouraging that the state has already created just about all the needed policy infrastructure. Additional tightening of emissions limits and targets will be needed, but the framework and policy mechanisms are largely in place.

Rajinder Sahota, deputy executive officer of the California Air Resources Board, contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Somebody needs to take the leadership role. Apart from energy consumption reduction, I would want to charge a battery backup to accumulate energy during non-peak hours. The goal would be to avoid the peak time of day price rate for electricity. And during daytime hours, solar could shoulder part of the electricity consumption burden.

For the sake of efficiency, we may have to stop owning cars, and put up with a robot system of public transport and private subscription vehicles. I had an electric car for a 3 year lease period and “servicing” involved little more than checking the tire pressure and washing the damn thing. It had terrible range and the charging station grid in California was less than impressive. Much better to let the robot deal with charging and range anxiety. Perhaps battery swapping is the answer. In any case, cars only spend about 5% of their time moving. The rest of the time they are “parked”, occupying space that could be used to grow zucchini or zinnias. Even Musk’s hyperloop facility was turned into a SpaceX parking lot. The US rail systems are still poorly integrated with transport so still many people commute intracity by car. Ultimately, the current model is inefficient, but using the rule of 10 (ten times cheaper, faster or better) used by angel investors, the new model would have to take vehicle activity from 5% to 50% (on the road half the time) or stated otherwise take 90% of the vehicles off the road. Parking would be replaced with charging or maintenance downtime. It is hard to imagine an America without large parking lots, but that would be a result of such a shift.

That’s an interesting wrinkle I hadn’t thought about, but I guess it makes sense. I wonder if that couldn’t be solved by including a fire suppression system in the battery enclosure. Or a waiver if the battery is in a separate structure from the home, like an outdoor shed.

Hydrogen was mentioned, but there are so many problems with that as an alternate energy source that I don’t think it’s going to make a dent in climate mitigation. Sabine Hossenfelder has a recent video diving into whether it’s practical or not:

Both electrics and hydrogen-based systems will be unpopular for a while. Due to combustion issues, Norwegian ferries are banning them.

There is a subgenre of news reporting devoted to Tesla spontaneous combustion events. E.g

In the end, though, we will adopt a system that makes uses electricity to make hydrogen that can then be converted back into electricity. Meanwhile, it may be many generations before we forget about the Hindenberg.

20 KWh should be plenty to get most homes through the dark hours.