This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

On Friday, President Joe Biden declared that “it makes sense” for unemployment benefits to expire in September. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki doubled down on his statement, noting that states have “every right” to pull the plug on this critical lifeline.

This couldn’t be more wrong. Strong social safety net measures like expanded unemployment insurance (UI) make our labor market stronger and are essential to an equitable economic recovery. And enhanced UI benefits disproportionately support Black and brown workers who continue to be left behind in the recovery: Unemployment rates for white workers ticked down to 5.1 percent, while the unemployment rate for Black workers remains nearly double that at 9.1 percent. And the unemployment rate for Hispanic or Latinx workers stands high at 7.3 percent.

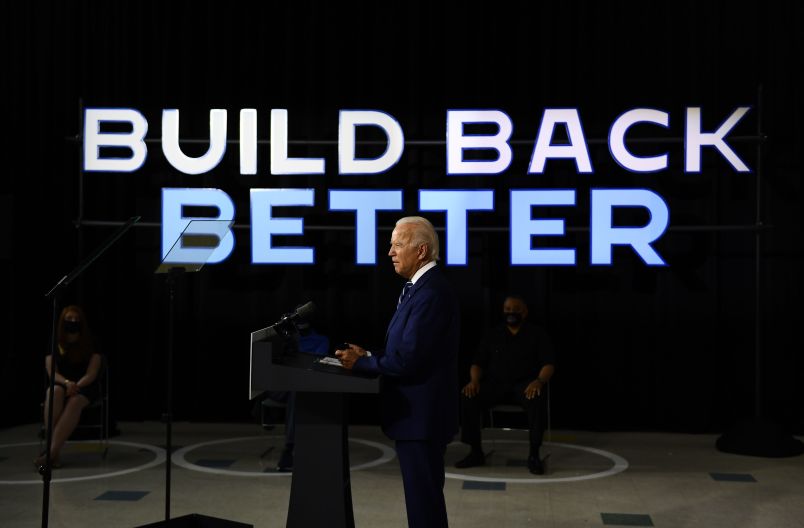

The American Rescue Plan provided a much needed boost for struggling workers, but turbo-charged investments are only as good as the system they’re pumped into — and we know that our unequal and unjust economy hasn’t worked, especially for Black and Latinx people, especially women, for decades. “Building back better” means fundamentally changing our collective understanding of what a healthy economy looks like.

Ultimately, the May jobs report tells us one thing unequivocally: It’s time to focus on the Black unemployment rate to ensure that we keep public investment going until all workers are doing well — not just the ones who always have.

Beyond unemployment insurance, we need to make a fundamental shift in how we measure our progress towards a more equitable economy. Aggregate economic indicators, such as the topline unemployment rate, erase the experiences of historically marginalized people, masking underlying inequalities. Frequently used economic models assume that even in a so-called “healthy economy,” the “natural rate” of unemployment for Black workers is about double that of white workers.

Structural discrimination and so-called “race-neutral” policy choices mean that the Black labor force as a whole has seen slower recovery rates compared to the white labor force. And in every economic recession of the last 50 years, Black women have endured higher unemployment rates than white men. Even a decade after the Great Recession — long after policymakers had become complacent about the need for recovery efforts — Black people’s recovery continued to lag behind their white counterparts.

A simple but effective step forward would be for both monetary and fiscal policymakers to more actively use the Black unemployment rate in decision making. In both realms, a focus on the Black unemployment rate would help ensure that policymakers don’t slam the brakes on the post-crisis economy before we have fully recovered.

The Fed is guided by a “dual mandate,” which sets interest rates to maintain stable prices while also keeping the unemployment rate as low as possible. As economists Jared Bernstein and Janelle Jones explained last year, when the Fed makes decisions about how to set the interest rate based on the overall unemployment rate, longstanding structural gaps between Black and white unemployment rates mean that Black workers are inevitably erased from the conversation. Notably, both Bernstein and Jones now hold key positions in the Biden administration at the Council of Economic Advisors and the Department of Labor, respectively.

But that is not — and should not be — a foregone conclusion. An increased focus on the Black unemployment rate would fundamentally change what the standards for a healthy economy looks like, and lead policymakers to think again before hitting the brakes on critical relief programs. But ultimately it’s not that big of a shift from the data we already look at. Rather, it is an important and easy to reach lever to ensure that we are building an economy that works for all of us.

The timing is ripe for change. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has increasingly signaled a shift over the past year to be intentional about addressing long-standing inequalities. Most recently, the agency has seemingly committed to confronting housing discrimination by requesting input to remake the Community Reinvestment Act. Now, it’s time for the Fed to act on such commitments and apply them to the biggest tools the Fed has: setting interest rates.

The American Rescue Plan has been a strong step in the right direction to address the immediate public health and economic crises facing workers and families. But building back better cannot mean returning to pre-pandemic levels of inequality.

If we truly want to recover, we need to not only provide temporary support, but also rethink how we measure — and address — these persistent racial and gender gaps in employment. And we must push back against outdated, conservative arguments about the deficit and inflation used to justify government inaction under the guise of “fiscal responsibility.” Because while the damage of the COVID-19 recession has been deeply unequal, our economic recovery doesn’t have to be.

Rakeen Mabud is the Managing Director of Policy and Research and Chief Economist at the Groundwork Collaborative. Follow her on Twitter @rakeen_mabud.

I know a couple HR directors at local companies. They need a variety of workers, skilled and unskilled, advanced degree down to not even requiring a HS diploma. Good benefits, good wages, opportunities for advancement, vacation, 401K match. Companies are known for being diverse and inclusive. Mixed race work forces. Despite extensive advertising and other methods they can’t find people, period.

I also know our city has a high unemployment rate among minority groups.

Explain.

Still a problem around here (which the Republicans refuse to acknowledge)is that many child care facilities have only reopened partially, if at all.

Biden has a plan for that, but…you know…Manchin…Republicans

“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” – FDR, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1937.

Even in the 20 years prior to the pandemic I don’t believe TPM has ever had a male African American writer on the staff.

Explain what?