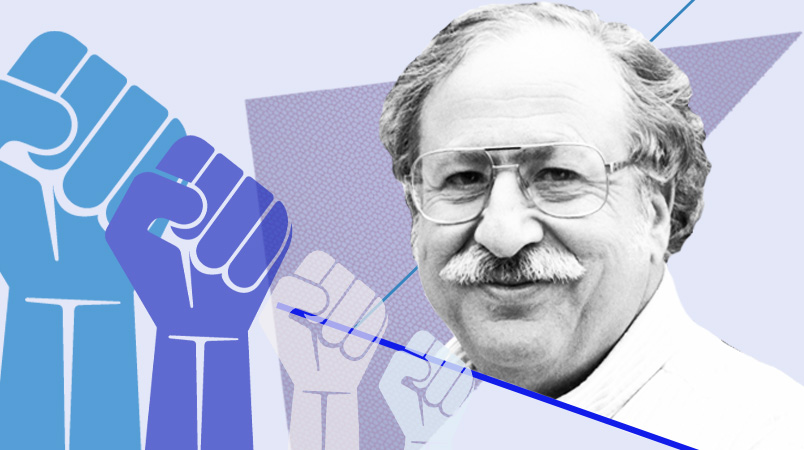

In the spring of 2007, famed union organizer Marshall Ganz began meeting with the Obama campaign. Ganz persuaded them to create a field operation using the techniques that Ganz had developed with the United Farm Workers in California. Thus the army of thousands of volunteers that helped Obama win the Democratic primary and the presidency in 2008 was born. Ganz, 73, is from Bakersfield, California, the son of a rabbi. He dropped out of Harvard in 1964 to work with a Southern student civil rights group, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The next year he moved back to California to join Cesar Chavez’s fledgling movement to organize the state’s migrant farm workers into a union, eventually becoming the United Farm Workers’ Director of Organizing. In 1991, Ganz returned to Harvard to get his B.A. and in 2000 received a Ph.D. in sociology. For three decades, he has been lecturing in the principles of organizing at Harvard’s Kennedy School, while remaining deeply involved in organizing projects in the United States and overseas. I wanted to ask him about the prospects of the left, liberals and the Democratic Party in the face of Donald Trump’s presidency and Republican control of Congress and the majority of statehouses.

Judis: We talked a few years ago after the Occupy movement fizzled about a Tahrir Square phenomenon [in Egypt], where protests rise up and then die off and achieve results contrary to what they intended. We now have tremendous protests against the Trump administration. What is going on? And what can come out of this?

Ganz: It takes a little hubris to say what is going on. It seems to be that what is happening is this overwhelming reaction to Trump’s assault on just about everybody other than his supporters in just about every way. It has created a solidarity in the face of a shared threat. One of the things that was interesting was that for the people who went to the Women’s March it wasn’t just about women’s issues and for the people who showed up at the airports it wasn’t just about immigration issues. There seems to be a moment of much broader recognition of the values that a progressive or democratic politics stands for. I think that is a great opportunity.

But the challenge is crafting that reaction into the capacity for strategic response. Unless this solidarity can become solidarity for shared purpose, we are going to dissipate a lot of it. Ever since the 1960s and 1970s, the problem on the progressive side, of fragmentation based on each group pursuing its own separate issue, seems to be far more substantial than on the other side.

Organizing opposition to Trump

Judis: How do you see this solidarity coming to pass. Doesn’t there have to be leading organizations at this point? One suggestion I’ve heard is that progressives have to focus on transforming and taking control of the Democratic Party.

Ganz: I don’t think so. There are a couple of places to look for instruction on this. For one thing, the rise of the conservative movement didn’t happen through the RNC [Republican National Committee]. Conservatives successfully created a more or less coherent network of organizations linked to local, state and national politics, which is a traditional form of effective political organization in the U.S. There was the Christian Coalition which started with school boards and moved upwards to take over the Republican Party. Or there is the Koch Brothers’ network. Not to mention the Tea Party or the NRA or ALEC.

The point is that it didn’t happen through the RNC. It happened through movements and movement organizations structured outside that could develop a coherent or at least semi-coherent strategy. If you go back to the civil rights movement, there was the Leadership Council for Civil Rights, it was everybody from the Urban League over to SNCC, and it lasted for a number of years. At least they knew what everybody was doing. They could disagree, but at least there was some sort of possibility of coherence, and occasionally they could converge, as they did on the March on Washington.

You look in vain for something like that on the progressive side. There is such a proliferation of groups, all kinds of groups, some of which take up space without filling it. Our challenge is to put together that combination of local, state and national organizations that can, first of all, handle defense, especially in terms of immigration because that’s an immediate threat to people’s security, and there is resistance on many fronts, but what needs more attention is initiative. If we expect the Democratic Party to do that we are smoking something because the closest they ever got was Howard Dean and his 50 state doctrine. I don’t think that’s where it happens. It happens through the stepping up of leadership at all levels to bite the bullet in a coherent way so that we can turn this opportunity to some real purpose.

The success of Indivisible is evidence of the enormous numbers of people out there who want to take action who are connected to no existing group.

Judis: What is Indivisible?

Ganz: They are a bunch of congressional staffers, one is an SEIU [Service Employees International Union] guy. They got the idea of doing to the Republicans what the Tea Party did to the Democrats. The put out a very simple, accessible manual of how to do that, and they got it out there in a very timely way, and it really clicked with people. They weren’t asking people to send emails or sign petitions. They are asking people to organize locally in the form of those town meetings they are having with the Republicans just like the Tea Party did. And it really took off. They’ve scaffolded some 7,000 groups. They are in every congressional district except for one. What they have done is to scaffold a barebones structure enabling people to focus on a specific tactic. Now the question is how they can take it to the next step. But that’s a very helpful development because of its scale, its depth and its simplicity. [For more on Indivisible, see this article. Or see their own site.]

I really want to underscore the significance of Indivisible. It’s the same experience we had with Obama in 2007 and 2008. You create a plausible pathway to action and all kinds of people come out of the woodwork. The problem is that there haven’t been many plausible pathways to action. And that’s a strategic responsibility, and it requires creating enough structure so that that kind of strategy can be developed and articulated.

Judis: What about Our Revolution, the Bernie Sanders organization?

Ganz: I don’t know enough to know what is happening. I know the Sanders campaign didn’t turn their mobilization into organization like Obama did. They did a lot of mobilizing, but the campaign wasn’t committed to organization. It was an Old Testament prophet at the head of the great multitudes.

Judis: Their focus seems to have been on getting Keith Ellison elected as the DNC chairman.

Ganz: The DNC is a distraction. If you look at what the RNC did for the Republican resurgence, it was not much. If you expect the DCCC or the DNC to do it for the Democrats, you’ll be disappointed. Dean temporarily defied the logic with his 50 state strategy. The usual business about not campaigning in every district is so counter-productive. If you look at it from a purely financial standpoint, we have to invest the money where there is the greatest marginal payoff, but it is all short-term. It is not looking at base building, so all these red areas never even hear a counter argument because nobody runs. It is not shocking that all they have is the Fox view of the world. It’s not being challenged.

Democratic politics depends on contention and challenge. One way to do that is through campaigns. It takes people with courage to run for school board. That is one piece of that I just don’t see happening through the DNC.

The goal is to organize, not just mobilize

Judis: The Republicans were rooted in Chambers of Commerce and the churches. Wasn’t that a big advantage to their resurgence?

Ganz: The Republicans had the evangelical churches, the religious schools that Betsy DeVos helped sponsor, the gun clubs, and the NRA. There are local gun clubs everywhere. There is this local infrastructure for their politics, and other than the unions, Democrats haven’t really developed much. Which is not to say they couldn’t.

Judis: Where does the impetus come from?

Ganz: It has to come from both the top and the bottom. But without the foundation at the base, it is just nothing. Many Democrats confuse messaging with educating, marketing with organizing. They think it is all about branding when it is really about relational work. You engage people with each other, creating collective capacity. That’s how you sustain and grow and get leadership. That’s how you make things happen. Organizers have known this for years. But then Green and Gerber at Yale showed that face to face contact with a voter, especially if relationally embedded, increases voter turnout. Broockman and others at Stanford showed interpersonal conversation— what they call “deep canvassing”—can change deep gender attitudes.

The gun clubs and the churches also have a reason to exist aside from advocacy. Part of the challenge for Democrats is to grapple with that. We did a study for the Sierra Club and we found that the groups that were most successful developing leadership were the ones with recreational activities. . The advocacy groups tend to be governed by rugged individualists far less interested in interpersonal activities. One of the things people loved about the first Obama campaign was that that they were campaigning for Obama but they were also interacting with each other, they were learning, they were growing. They built these local groups, they were being effective, and that’s what we want from our lives. We want to feel we are effective. So I think Democrats can do a hell of a lot better job than they have been doing.

Judis: Besides Indivisible, are there any other things that you see on the ground that could be the basis for this movement building.

Ganz: Surely the whole mobilization around immigration and Muslim-bashing, the immigration challenge, I know there is a lot of infrastructure there, a lot of it is organized to resist what looks to be coming. There are groups like Our Future that are trying to get together a lot of the more traditional advocacy groups. I don’t know how to assess that. I do hear that there are lot of people in Washington going to a lot of meetings, but whether it translates into anything effective beyond Washington remains to be seen.

The action in purple and red states has to be old fashioned organizing. There is an article in the Nation by Jane McAleevy that is really good. She distinguishes between organizing and mobilization, and she talks about Wisconsin and all this mobilization that took place, but that when it got down to the base, the capacity to defeat Governor Scott Walker wasn’t built. It’s like organizing a union.

When you are organizing a union, a workplace, you have got to organize who’s there. One of the troubles with the progressive groups is that they respond to those who already agree with them, but don’t have much incentive to actually go out and build a base by persuading and engaging and converting those who don’t. If you are organizing a union, you have to do that, because that’s how you win. Now ignoring all these red and purple states is like pretending you don’t need them to win, but you do. That takes organizing. it’s intense, it’s relational.

The need for a Bernie politics

Judis: You talk about engaging and converting those who disagree with you. One of the big issues where Trump voters and Clinton voters disagreed was illegal immigration, and you mentioned immigration groups as leading the charge now against Trump. Many union voters backed Trump because of his outspoken opposition to illegal immigration. How can liberals and Democrats engage these voters when they won’t even use the term “illegal immigrants,” and generally don’t talk about the need to enforce America’s borders.

Ganz: I guess the way I see it is that the anti-immigrant stuff is a function of the neo-liberal politics of the last forty years. These politics haven’t addressed the real questions of inequality that include race, economics and immigration all together. They have created this setting where the frustration over inequality turns into an attack on immigrants. That’s a very old tradition in American politics going back to the Irish and even before.

That is a kind of standard deflection that the powers-that-be employ. So the challenge is to engage with people in what the real problem is. You have to challenge the relationship of Hillary [Clinton] and Goldman Sachs. You need a Bernie [Sanders] politics. Maybe we need a combination of Bernie and Obama and Hillary at their best, some sort of plausible motivational alternative to Trump’s solution to the problem. If you have that going, then you have something to talk about.

If you are just saying “Don’t hate immigrants,” well don’t hate immigrants. If I am convinced that’s the source of my impoverishment, it’s a problem. The reality is that it’s not. And that’s why I say it’s a lot like union organizing. When you are organizing a union, the bosses are always trying to divide. It’s a time-honored tactic, and the only way to fight back is to have an alternative moral and strategic account of why we are the way are. We got some of that from Bernie. We didn’t get any of it from Hillary.

You need a story about a future that can be built based on democratic values, Bernie articulated some of that. But it’s most powerful if it can be enacted locally as well as nationally. I think one of the smart things the Christian Coalition did was starting to organize locally around school boards. Because then you can take over the schools and change the text books. That was a step toward this whole national mobilization that was going to happen.

Democrats need to learn to tell a story that links shared values with plausible goals, like JFK’s Peace Corps or Man on the Moon; Bernie’s free college, universal health care and good jobs; or Trump’s wall in the South, Muslim ban and trade deals. It’s not 500 pages of policy documents.

Judis: So we came closest to that with the story Bernie Sanders told during the campaign?

Ganz: Yes, Bernie was the closest to it. Of course, Bernie had a problem incorporating the stories of racial and gender equality, especially racial equality along with economic inequality. My own view is that that stuff came apart in the late ’60s and early ’70s, when King was assassinated and Bobby Kennedy was killed. Economics became disaggregated from race and gender. That didn’t even deal with the problems of most women and people of color, which has to be dealt with in economic terms So the focus on gender and race facilitated an openness to the most resourced of their communities coming up through hierarchies, but not on restructuring the hierarchies. So we have to do something to bring race, gender and economics back together.

We also have to create structures that enable us to strategize and organize, and we a need strategy that targets every district. It’s like what Indivisible seems to be doing. Everyday you get stuff, and there are people trying to coordinate groups and activities. I’m impressed with that. Indivisible seems to combine local and national scale and seems to be creating some organizational foundation.

Comparing Obama and Trump

Judis: I want to introduce a somewhat different subject. You have criticized what happened when Obama made the transition from campaigner to President. In one column, you accused him of not using the bully pulpit, compromising rather than advocating and demobilizing the movement his campaign had built.

Ganz: [Saul] Alinsky said you have to polarize to mobilize and depolarize to settle. Obama was depolarizing when he needed to be mobilizing. It’s galling to remember how Republicans have come in with a one-vote majority or no majority at all, and they have treated their election as a mandate, and Democrats have come in with a solid majority and they have treated it like something they have to prove they are entitled to. Obama’s whole approach was to minimize opposition rather than to maximize support. He was in a position to maximize support, but what he did was try to get everyone who was opposed to support. It was a feckless task, and it led to the weirdness of the ACA [Affordable Care Act] and the rest of it.

Obama also failed to take on the economic problems in the country. That’s where everybody’s head was, but there was this disconnect with where he was and where the American public was in terms of urgent needs that needed government action. He got the stimulus, but it was never marketed, it was never explained, nobody ever understood it. He turned the role of advocate and change agent into something that was quite the opposite. And the organization that was built was just left hanging. And it really had nothing to do. They used it a little bit on the healthcare thing. But to have given it life would have required separating it from the administration.

When politicians lose they are all for separate organizations, when they win, they don’t like them so much. Obama wasn’t going to go with a separate organization. His White House’s need for control was so huge. They thought they were just going to do the whole thing, and the tables that had been assembled in DC, the environment, immigration and labor reform, were neutered.

Judis: Now let’s talk about Trump. If you heard his inaugural address or his speech in Melbourne on Feb. 19, Trump was doing a lot of what you wanted Obama and the Democrats to do. He was telling a story about “making America great again.” He was calling for a movement. He was using the bully pulpit. He was advocating not compromising. Isn’t he doing exactly what you wanted Obama to do after he got elected? Isn’t he following your script?

Ganz: Pretty much. I think the big difference other than the specific values is that at the core, Trump is saying “Follow me and I will take care of you.” It’s mobilizing, but it’s building a movement around dependency. It’s a fear-based movement. Obama or Bernie were inviting their followers to greater agency and autonomy, not less. And that makes all the difference in the world. Their campaigns weren’t about creating dependency on some great leader who is going to save you from everything.

There is a very good book by Robert Paxton, “The Anatomy of Fascism.” If you look at his analysis of fascist politics and how it works, there is a lot of resonance with this guy. I mean a lot. It’s not Germany in 1933, but it helps understand what is going on, the performative character of it, the unpredictable character of it, the leader-centrism, the demand for utter loyalty and obedience. It’s tribal in its hold.

Judis: He is not organizing a movement the way Hitler or Mussolini did.

Ganz: This doesn’t seem to be there, and yes, before television, everyone had their movements. There was always tension between the fascist movement and the government. Trump doesn’t have that to deal with because he doesn’t really have a mass organization. If he built one, that would be something. I can’t imagine him doing so, but a lot of things have happened that I can’t imagine.

The Trump voters

Judis: What about his base? I hear a lot of liberals saying that Trump’s movement is based on white nationalism or white supremacy. How much that is the case?

Ganz: Racism plays into what are in essence economic and status grievances. There has always been racism in America. There was always ethnic sentiment in Yugoslavia before Tito died, but then every local politician hoping to build a base had an interest turning ethnic identity into the nightmare it became. So it is more a question of what makes it salient, dominant and powerful in a particular time and place.

Generations change. We saw how younger white people in South Carolina voted for Obama while their parents didn’t. Eventually, the tide is turning in the right direction. But what has given racism salience is the way Trump uses it as a basis for fighting back against the status loss and economic uncertainty. When it comes to organizing at the base, it goes back to what I said earlier, you have to have an alternative account. You have to have a different story of why things are screwed up. Bernie came closest to that of anybody recently.

Judis: And the Clinton campaign ignored having an alternative account?

Ganz: They neither motivated their own base nor did they take on his base. They didn’t try to promote Hillary. They tried to undo Trump, but not by offering a powerful alternative. There were ads saying this guy is a racist. What does that do for me?

Bernie was talking alternatives. Hillary wasn’t talking alternatives.

Judis: Trump has talked about certain issues that the left would talk about, including NAFTA, drug prices and runaway shops.

Ganz: Yes, of course, but it remains to be seen what that turns into. In organizing, you hear the bosses talk all the time about these things they would do through company unions. Doesn’t it seem like it is all going to be a big tax rip-off? To the extent the infrastructure gets built at all, it will be built in sort of a kleptocratic fashion. It remains to be seen, but it would hard for me to believe that he could deliver at all, and that whatever he delivers would look even vaguely progressive.

Judis: Yes those issues have not been talked about by liberals except for Bernie.

Ganz: Look at the Kennedy School. They teach neoliberal economics. Ever since the DLC [Democratic Leadership Council] and the Clinton presidency. What [Dwight] Eisenhower did for [Franklin] Roosevelt by accepting the New Deal, and Clinton did for [Ronald] Reagan. He accepted that government is the problem, and all this neoliberal stuff flows from that period.

Judis: And the Trump people, and Bannon, understand that?

Ganz: Oh yes.

Judis: And that is some of their appeal?

Ganz: You got to take it on, it’s not enough to tear it down. You have to have your alternative. You can’t convince people by saying just don’t do that.

Identity politics and issue silos

Judis: Is identity politics a problem for the Democrats?

Ganz: I think it is real, but it means different things. It is critical to find ways to show that racial and gender and economic inequality are deeply interconnected, and that you really cannot deal with one successfully without dealing with the others. We dealt with economics until the 1960s and 1970s and then we shifted more to race and gender. So the message here is that you got to get it all together. It is about power. If you say, okay, I’m going to fight racial disempowerment but I am going to ignore economics, you are also ignoring the disempowerment of huge portions of the black community.

The problem is coming up with a whole that is less than the sum of its parts. It is not to deny the validity of identity politics. The question is: how do we do what we want to do unless we attack inequality on all its faces. That is what democratic politics demands.

Judis: And what about an issue-oriented politics?

Ganz: It’s also a problem when people define themselves in terms of their issue. I am a tree person. There is someone else who is a school person. What it does is fragment the hell out of stuff. You saw in Obama in 2007 and 2008, it was very energizing for people to get out of their issue silos and come and work with other people with whom they shared basic values on a common strategic goal, which was to get the guy elected President. The power is in choosing issues strategically, not based on defining yourself by your issue. That’s been another big problem for progressive groups.

It is reinforced by a funding system that funds people based on product differentiation. So you’ll only get funding if you are different from other group. There is a proliferation of groups out there just because funders think they should exist.

Judis: How has that worked?

Ganz: The civil rights movement was funded by labor and churches, a couple of small foundations and the Kennedy-sponsored Voter Education Project It was the movement driving the funding, not the funding driving the movement. But what has happened in the last 20 or 30 years, there has been a real shift.

It began with Reagan’s campaign to defund the left, a campaign to systemically do away with funding sources for progressive and community organizing and all the rest of that. During that time, a lot of groups did canvassing to raise money. Then as the wealth began to accumulate in the 1990s, the wealthy came along and said, “Well I have made so much money, and want to do this about schools, and I want to do that about the environment.” They use their wealth politically to fund this candidate rather than that one and to fund groups to do what they think needs to be done. So there is all this pressure on groups that don’t know how to organize their own constituency to listen to the wealthy donors. The whole idea of constituency-based, member-based organizing, which unions exemplified, has just disappeared from the advocacy world. So everybody is dependent on the funders and writes their proposals to fit what they want. And in the process, these groups haven’t really built a constituency they can mobilize and represent.

Immigration as a divisive issue

Judis: I want to return in conclusion to the issue of immigration as a key dividing line between Trump voters and liberals or the left. When you were with the Farm Workers, Cesar Chavez was very critical of illegal immigration. And you only got a union when the government ended the Bracero program, which brought guest workers in. Do liberals and the left give sufficient recognition to the concerns that people have about illegal immigration?

Ganz: To me, it still comes back to the same thing. The immigration reform bill that almost got passed was not some radical thing, but what it did offer was a pathway to citizenship and normalization of the whole scene. To me that is really the only option.

Judis: But we are not talking now about policies. We are talking about stories. If you listened to Hillary Clinton you never heard about how we have to protect and secure our borders. You did hear about we have a path to citizenship. Isn’t there a way in which the issues themselves get presented that make it very difficult to reach over to the other side, that creates a kind of polarization that you don’t want?

Ganz: I think that certainly can happen. Anytime there are movements, you are going to have various versions. We certainly had that in the civil rights movement. But it seems to me the point is to recognize reality. There is very little support for the notion that the presence of undocumented immigrants here affects wages. The wiping out of unions affects more than that. To me, it represents the painting of a false issue, and things said about them are the same that were said about the Irish and everybody else. They are part of the economies of Arizona and California and Texas.

I hear what you are saying. It’s a good issue for them to use. What we have to do is to take the issue away from them not by agreeing with them, but by putting it in a different context, which is not immigration. To me it underscores even more the need to offer an alternative economic account not in the sense of competition from undocumented workers, but economics in terms of corporate profits, in terms of labor law, in terms of all the stuff that they have taken away for the last forty years.

Get organized???

In most cases it’s the HIGHEST SCORE that wins.

Maybe the better questions is, how do we GERRYMANDER like the cheating Republican’s did and get away with it. They did it why can’t we?

The Republicans are EXPERTS at stealing elections…Data bases which conatain voter information cans translate into gerrymander maps by district, might have something to do with it. Skillfully managed by the crooked Republican think tanks have learned this skill very well.

Gerrymandering is VOTER SUPPRESSION.

I hope we can learn frpm the crooked Right. I really want to take control back and then keep it. They cannot be trusted. The American way is NOT their way. They’re selective in their process and exclusive to their white-male-base. They’ve proven to be UNAMERICAN by their exclusive attention span, paying close attention to only their own…puppets on the strings of Corporate America. It’s hard to figure out why the Republicans that vote cannot see the damage they’re doing to themselves…it’s qyite deplorable.

Excellent interview. Basically, the left has become too dependent on the Democratic party, too dependent on pinning their hopes on the next Messiah hopefully showing up every four years that will solve all of our problems, and too dependent on mobilization without organization. Of course, the left should not abandon the Democratic party, but it must have an organizational infrastructure outside of the party if it intends to get anywhere in the next 8 years.

The Republicans got their gerrymander because they were well organized on the state level, while Democrats sat home and watched “Dancing with the Stars” in 2010. Republicans didn’t steal elections, Democrats and the left lost them. As long as we throw up our hands and proclaim “Republicans stole the election” instead of not taking responsibility for our losses, we’re doomed to repeat these failures. .

So-called “progressives” who can’t win an election for dog catcher keep lecturing everyone about how to conduct the class struggle.

I find myself disagreeing with much of what Ganz says. Hillary got the most votes. She didn’t have the right distribution because the FBI corrupted the political environment in which votes were cast by painting her with a false cloud of criminality, and people who largely agreed with her policy agenda but didn’t have a personal affinity for her didn’t want her to be President even if it meant that Trump became President.

The best way to analyze the swings which determine how elections are decided is through analyzing base human behavior, how people actually behave vs. what they say. At the end of the day, the Berner rejection of Hillary had nothing to do with policy. She campaigned on a Berner agenda. She adopted a Berner platform. She used that agenda to win 3 of 3 debates. It was about personality at the end of the day. They liked Obama but didn’t like her, plain and simple, even though it is objectively provable that she was more progressive than Obama. Al Gore 'lost" for the same reason even though he was far more progressive than Bill Clinton.

Left wingers talk about idealism and philosophy, but they’re motivated by base instincts just like the Republicans. Why is it that the Berner movement was white male dominated? Because it was a way for such folks to establish an alternative power base as the establishment party was comprised of women, minorities, and relatively wealthier/older white Democrats. The Berner movement was as much a white counteraction to Obama as was the Trump movement. Normal people got sandwiched in the middle by this nonsense.

Lesson for '20: get a candidate with a sane agenda, good favorables and is ok with guns as they are, and you have a winner.