Anti-Muslim sentiments and paranoid fears about sharia law are still taking center stage in our political and social debates. GOP presidential candidate Ben Carson’s concerns about the possibility of a Muslim gaining the presidency and his insistence that such a candidate would need to “renounce Islam” before taking office are, nationally syndicated columnist Cal Thomas writes, “caution, not bigotry.” The mayor of Irving, Texas—home to 14-year-old engineer Ahmed Mohamed—argues that her anti-sharia and anti-Muslim sentiments are “exactly what the American public is thinking.” And judging by stories such as this one, describing fears of a Muslim takeover of South Carolina in response to the idea of Syrian refugees coming to the U.S., there are indeed many Americans who share these concerns.

Given that Muslims are one of the oldest American communities—including, ironically but tellingly, a Moroccan Muslim community in Revolutionary-era South Carolina—there’s no doubt that these 21st century fears reflect much of what has changed in the last couple decades: the September 11 attacks and all that has followed them, the global War on Terror and the surveillance state it has spawned (one all-too-frequently targeted directly at Muslim American communities), the rise of ISIS and the Charlie Hebdo massacre and so many other recent and ongoing histories.

Yet at the same time, these anti-Muslim narratives, these paranoid fears and conspiracy theories about Muslim immigrants and communities and sharia law, echo quite closely another American history: centuries of anti-Catholic sentiment in the U.S. And remembering and engaging with those histories, in a moment when national attitudes toward Catholics have so obviously shifted, offers a telling glimpse into how our anti-Muslim narratives might look to future historians.

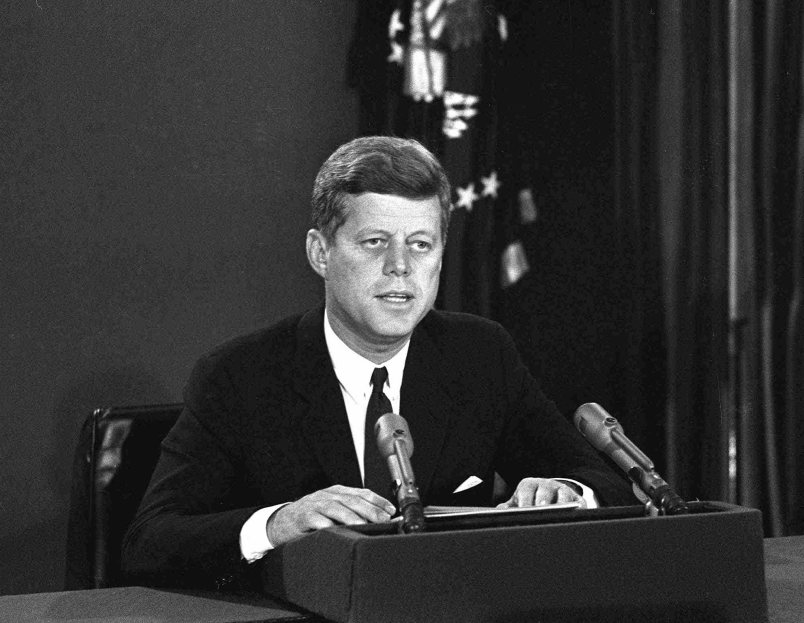

To begin with the most famous example of anti-Catholic fears: Ben Carson’s warnings about a Muslim president sound almost identical to many concerns raised about John F. Kennedy as he ran for the presidency in 1960. Would Kennedy answer first to the American people, or would his first allegiance be to the Vatican and the Pope? Would he be willing to renounce that international religious allegiance—that membership in a cult conspiracy, went the mostly unspoken but clear subtext—before assuming our highest office? Kennedy’s campaign represented one crescendo of these paranoid anti-Catholic fears, but in that mid-20th century moment they can be traced back to influential figures such as Paul Blanshard, the journalist (for The Nation, proving that these sentiments can come from anywhere on the political spectrum) whose book American Freedom and Catholic Power (1949) was a national bestseller.

If we extend our historical gaze further back, we can find even more overt anti-Catholic echoes of our contemporary narratives about Muslim Americans. New York Governor Al Smith’s 1928 campaign for the presidency was significantly affected—if not indeed derailed—by anti-Catholic fears and accusations, including a note sent home with Florida schoolchildren reading “If he is elected President, you will not be allowed to have or read a Bible.” The 1920s resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, one that saw the organization become far more widespread than in its Southern late 19th century origin points, likewise tapped into these national anti-Catholic narratives. At the 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City, in which Franklin Roosevelt attempted to nominate Al Smith, a sizeable Klan contingent protested Smith’s allegiance to the “Whore of Babylon” (the Pope) so vocally that the process deadlocked and an alternative nominee was selected.

Nineteenth-century anti-Catholic paranoia was perhaps even more overt and extreme. Lyman Beecher, the prominent minister and theologian who was also Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father, wrote the book A Plea for the West (1835) to make the case that Jesuit missionaries in the western part of the continent were creating Catholic strongholds that would lead to a Papist takeover of the nation if they were not expelled. Before it was revealed to be a thorough fabrication, Maria Monk’s hugely popular book Awful Disclosures (1836) alleged widespread corruption, vice, and evil among the nation’s Catholic priests and nuns. Responding to these and other influences, the nativist movement and Know Nothing political party of the 1840s and 1850s focused much of its attention on Catholic immigrants, creating a platform (including for an 1856 presidential run) dedicated in large part to excluding Catholic arrivals as well as attacking their existing American communities.

While the Know Nothings did not win the presidency, such anti-Catholic sentiments never vanished from American life, and found resurgence with the ‘20s Klan, Blanshard’s book, and the anti-Kennedy narratives. Yet thanks in part to Kennedy himself, as well as to many other factors in the changing tides of national identity and community, half a century after that 1960 election the nation has collectively welcomed Pope Francis to our shores on so many levels: from a speech to Congress to events and celebrations in multiple Northeast cities, events featuring millions of American Catholics as well as this most prominent international icon. Conservatives may be wary of Pope Francis, but it’s not because he’s Catholic. Clearly, we have communally recognized that we have nothing to fear from Catholics, domestic or foreign.

2015 is not 1960, and there are as always specific historical issues and factors with which we can and must engage. Yet our current anti-Muslim Know Nothings will look just as extreme and silly to future historians as do those from the 1850s, the 1920s, and the Kennedy campaign.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

There’s a huge element of racism in Islamophobia that does not exist in ‘yesterday’s fear of Catholics’, not to mention we’re living post 9-11, and all the xenophobia that brings along. Comparing the two is laughable.

I vividly recall this hysteria. One specific memory… a big community revival to hear a pair of evangelist brothers (whose names have faded from memory), in about 1950 or so, when I was a teenager and very devout. These guys spent a good share of their long program orating about the terrible threat of Catholicism; they gave “examples” of those horrors from South America and other places that sounded very exotic to people in my bible-belt small town. I wasn’t quite clear what those nasty Catholics were going to do to us all but it sounded credible and very scary! This sort of propaganda was finally undercut by Kennedy’s campaign and his adherence to his promise not to let the Pope dictate politics here, and its prominence in our minds largely displaced by other hysterias. In those days the current preponderance of Catholics on the SCOTUS would have been anathema–they’d never have been confirmed.

What color were all those South Americans? I pretty much thought of them as brown-skinned, though I had no problem with that personally. No, their color was not stressed directly… but I recall that those evangelists offered a good bit of racism in their spiel too, interwoven with the “the Catholics are coming!” hysteria. In retrospect that might explain something that always puzzled me… why they chose S.A. Catholics vs, say, Europeans, to exemplify the frightening stuff. The Pope was in Italy, not Brazil, after all.

Yup. And the Mexicans are the new Irish, just like the Italians, the East European Jews, and the Chinese. Same anecdotally driven baseless calumnies about drugs, criminality and supposed resistance to learning English and assimilating, different decade.

Actually the Irish Catholics were not considered “white” at least for a good chunk of American history.

My wife’s Irish Catholic great grandparents disowned their daughter when she married a Sicilian Catholic man - because they viewed him as “black.”

However when we view the results of the current Catholic-majority Supreme Court, we might honestly regret that Catholics now have a privileged place at the table. Having a religious minority injecting their “morality” into our laws is not what the Founders desired. Looking at Scalia and Alito and Thomas in particular, it’s obvious they are demented by religion and incapable of rational judgment. Protestantism can do that too, obviously. But historically, have we ever had a high court as warped by religion as this one?